|

November 2010 Updates

Chanukah Blessing Cards

[ Note: Chanukah begins Wed. Dec. 1st and runs through Thurs., Dec. 9th this year. If you have never personally experienced your own Chanukah celebration, let me encourage you to purchase a Chanukah menorah and light the candles along with us this year. Step by step instructions are provided on the Chanukah pages on this site, chaverim. ]

11.30.10 (Kislev 23, 5771) The Chanukah Blessings page includes some free "Hebrew Study Cards" you can use for your Chanukah celebrations! This year I have added a new Messianic version of the candle lighting blessing that can replace the traditional (i.e., rabbinical) version. I created downloadable cards for each of the key blessings, including the Messianic declaration that Yeshua is the Light of the World.

Chanukah Blessings:

- Yeshua, the Light of the World (anochi or ha'olam) - During Chanukah candle lighting ceremony, we make it a point to reaffirm the glorious truth that Yeshua is the Light of the world. Those who follow Him will have the light of life (John 8:12).

- Traditional Chanukah Candle Lighting Blessing (hadlakat nerot Chanukah) - This is the traditional blessing recited before kindling the candles on your chanukiah. The custom is to light one candle on the first night of Chanukah, two candles on the second night, and so on until the eighth night when all eight candles are lit. In this way we remember the 'growth' of the miracle.

- Mesianic Chanukah Candle Lighting Blessing (natan lanu chaggim) - Some followers of Yeshua object to the traditional blessing and its statement that we are "commanded" to light the Chanukah candles, and therefore choose to recite an alternate blessing.

- The Miracle Maker Blessing - (She'asah Nissim) - This blessing recalls the miracles of the Chanukah season (note that the same blessing is recited during Purim). We recite She'asah Nissim every night for the holiday, usually just before or immediately following the kindling of the Chanukah candles.

- The Shehecheyanu blessing ("Who has kept us alive") - Recite this blessing for the first night of Chanukah only. The Shehecheyanu has been recited for thousands of years to mark moments of sacred time in Jewish life. It is referred to in the Talmud and other ancient Jewish literature (Berachot 54a, Pesakhim 7b, Sukkah 46a).

- The Closing Paragraph (Hanerot Hallelu) - This statement is recited (or sometimes sung) after the candles have been lit. It is intended to remind you of the sanctity of the occasion and to help you remember not to use the Chanukah lights for profane purposes. After it is recited, a seudat Chanukah (a special meal) is eaten, with special songs of praise and prayers.

Of course Hebrew audio clips are provided on the Chanukah blessings page as well. I hope you find the cards helpful, chaverim! Chag Chanukah Sameach (חַג חֲנֻכָּה שָׂמֵחַ)!

Some Reasons Why...

Christians Should Celebrate Chanukah

[ The eight day celebration of Chanukah begins after sundown on Wednesday Dec. 1st (i.e., Kislev 25) and runs through Thursday, Dec. 9th this year. In the following entry, I provide a few reasons why a follower of Yeshua might choose to observe this special holiday season. Note that I wrote this in some haste, so you might discover a typo or two here. I also have been sick with a cold/flu the last few days, and that has slowed me down a bit. I wish you all a wonderful Chanukah season. Let your light shine! ]

11.30.10 (Kislev 23, 5771) The story of Chanukah begins with the reign of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), the student of the renowned pagan Greek philosopher Aristotle. In 333 BC, Alexander conquered Syria, Egypt and Babylonia, and promoted a lenient form of Hellenistic culture, encouraging the study of the language, customs and dress of the Greeks. After his death, however, a series of civil wars tore his empire apart which resulted in the formation of a number of states. Eventually the "Hellenistic world" settled into four stable power blocks: the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt, the Seleucid Empire in the east, the Kingdom of Pergamon in Asia Minor, and Macedon. Many of these areas would remain under Greek control for the next 300 years, though the legacy of Hellenism continues to this very day.

Many Bible scholars say that the prophet Daniel (6th Century BC) foresaw the rise of Alexander the Great centuries beforehand in the vision of a "male goat running from the west" that had a conspicuous horn between its eyes (Dan. 8:1-12; 21-22). This goat destroyed the power of the kings of Media and Persia (symbolized by two horns on a ram, Dan. 8:20). Though the "goat" (Alexander) became exceedingly great, eventually its horn was "broken into four [kingdoms]", and out of these four horns arose a "little horn" (i.e., the Seleucid king Antiochus "Epiphanes," c. 175-163 BC) who had authority over "the glorious land" (i.e., Israel). This "little horn" (קֶרֶן מִצְּעִירָה) greatly magnified itself, cast down some of the stars (righteous souls), took away the sacrifices, and defiled the sanctuary in Jerusalem. Antiochus is perhaps most notorious for setting up an altar to Zeus over the altar of burnt offering in Temple and sacrificing a pig on the altar in the sanctuary of the Temple itself. This event is known as the "abomination of desolation" (שִׁקּוּץ מְשׁמֵם) that was decreed to occur 2,300 days into Antiochus' reign (Dan. 8:13-14). Notice, however, that Daniel's prophecy has a "dual aspect" to it, and the description of the rise of the "little horn" (in Dan. 8:9-10) suggested something far more portentous than the reign of a local tyrant. This horn "grew exceedingly great toward the south, toward the east, and toward the glorious land. It grew great, even to the host of heaven. And some of the host and some of the stars it threw down to the ground and trampled on them." In light of other New Testament scriptures, it is clear that this "horn" refers to future world leader (sometimes called the "Antichrist") who would one day attempt to "assimilate" all of humanity into a "New World Order" (Dan. 9:26-27, 2 Thess. 2:3; Rev. 13:7-9, etc.). It is likely that it was this sense of the "abomination that makes desolation" that Yeshua referred to in Matt. 24:15 and Mark 13:14, and it is this "abomination that makes desolation" that will be overthrown by Yeshua at the end of the Great Tribulation period (Dan. 8:23-25; Matt. 24:30; Rev. 19:11-16; 20:2, etc.).

The books of Maccabees (c. 2nd Century BC) tell us more about this "little horn" and his oppression against the Jewish people. Antiochus installed Hellenistic Jews to the priesthood and demanded the adherence to Hellenistic cultural ideals. He established edicts that prohibited observing the weekly Sabbath and the other biblical festivals. The reading of the Torah was outlawed and all copies of it were ordered to be burned. Temple sacrifices were forbidden; circumcision was outlawed and the penalty for disobedience was death. Women who disobeyed the edict by circumcising their sons were paraded about the city with their babies hanging at their breasts and then thrown down from the top of the city wall (2 Macc. 6:1-11). Many Jews fled and hid in the wilderness and caves and many died kiddush HaShem - as martyrs (see Heb. 11:36-39). Eventually Jewish resistance to this imposed Hellenization meant war. In 164 BC, in Modin, a small town about 17 miles from Jerusalem, Mattityahu (Matthias), a Hasmonean priest, and his five sons took refuge. When Antiochus' soldiers arrived at Modim to erect an altar to Zeus and force the sacrifice of a pig, Mattityahu and his sons rose up and killed the Syrians. They then fled to the Judean wilderness and were joined by other freedom fighters. After some organizing, they soon engaged in successful guerrilla warfare against their Syrian/Greek oppressors. The three-year campaign culminated in the cleansing and rededication of the Temple (for more on this subject, see Chanukah and Spiritual Warfare).

In addition to the prophecy of Daniel and the historical events leading up to the rededication of the Temple as described in the books of Maccabees, there is other evidence that the festival of Chanukah was a part of Jewish history and tradition before the time of Yeshua. The most important piece of evidence comes from the New Testament itself (1st Century AD), where we read that during the "feast of dedication" (i.e., Chanukah) Yeshua was "walking in the Temple in the colonnade of Solomon" (John 10:22-24). Notice that this is the only reference to the festival of Chanukah (חַג חֲנֻכָּה) that occurs in all of the Jewish Scriptures. Some additional "extra biblical" sources include the testimony of the first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, who likewise referred to the commemoration of the Maccabees as an eight day "festival of lights" (Antiquities XII), and various midrashim that quote Hillel and Shammai (i.e., two famous sages that predated the time of Yeshua) discussing the method of kindling the lights of the Chanukah menorah. One midrash states that Chanukah was to be regarded as an acronym for Chet Nerot veHalakhah K'bet Hillel ("eight candles and the law according to the House of Hillel"), referring to Hillel's view that we should light one candle on the first night and increase the amount by one every day (Shammai, on the other hand, thought we should light eight candles on the first night and reduce one every subsequent night). According to early Jewish tradition (preserved in Megillat Antiochus, 2nd Century AD), since the Maccabees were unable to celebrate the holiday of Sukkot at its proper time in the fall, they decided that it should be observed after the Temple was restored, which they did on the 25th of the month of Kislev in the year 164 B.C. Since Sukkot lasts eight days, this became the timeframe adopted for Chanukah.

(As an aside, I should add that the Talmud later attests that the celebration of Chanukah was a part of ancient Jewish tradition. Both the Mishna (Rosh Hashanah 1:3, Megilah 3:6, Bava Kama 6:6) and the Gemara (Shabbat 25b) refer to the holiday: "On the 25th of Kislev are the days of Chanukah, which are eight, appointed a Festival with Hallel [praise] and thanksgiving" (Gemara: Shabbat 21b, Bavli). In general, however, the Talmud, does not discuss Chanukah that much, doubtlessly because of the later need to establish the Pharisees as the (exclusive) leaders of the Jewish people after the destruction of the Temple, and also because of the controversy surrounding the Hellenistic priesthood. Therefore the Talmud's statements (recorded centuries after the Maccabean rebellion) focus on the miracle of the oil rather than on the merits of the Maccabean resistance. Later rabbinical tradition sought to find Chanukah alluded to in the text of the Torah itself. First, the 25th word of the Torah is or (אוֹר), "light," as in "Let there be light" (Gen. 1:3), and this suggested Kislev 25, and second, immediately after the various festivals (moedim) of the Jewish year are enumerated in Leviticus 23, the commandment to "bring clear oil from hand-crushed olives to keep the menorah burning constantly" is given (Lev. 24:1-2), and this was claimed to foretell the miracle of Chanukah.)

Years after the Maccabean revolt, Yeshua celebrated Chanukah in the same Temple that had been cleansed and rededicated only a few generations earlier (John 10:22). It was here that many asked if He were the coming Messiah - harkening back to the liberation of the earlier Maccabees: "How long will you keep us in suspense? If you are the Messiah, tell us plainly" (John 10:24).

Recall that during the Second Temple period, there were four primary "sects" or "denominations" of Jews living in the land of Israel. The Saduccees (i.e., צַדּוּקִים, "righteous ones," from Tzadok the priest) were Hellenistic Jews who controlled the Temple; the Pharisees (i.e., פְּרוּשִׁים, "interpreters") were Torah scholars who sought to teach the common people how to live the Jewish life; the Essenes (i.e., אִסִּיִים, perhaps from oseh hatorah: עוֹשֵׂה הַתּוֹרָה, "doing Torah") were mystical ascetics who repudiated the Hellenized priesthood (i.e., Sadducees) and moved to the Judean desert (near the Dead Sea) to await the apocalypse; and the Zealots (i.e., הַקְנָאִים, "ardent ones"), who were political agitators that sought to incite the Jews to rebel against Roman rule by force of arms, if necessary. It is likely that Chanukah was a favorite holiday of the Zealots, and it was on account of their mistaken conception of the Kingdom of God that eventually led the Jewish-Roman wars and the destruction of the Second Temple, as prophesied by Yeshua (Matt. 24:1-2).

It is perhaps easy to overlook the Messianic expectation connected with a festival that celebrated the "rededicating the Temple," but clearly there were many zealous Jews who were "in suspense" regarding the arrival of the greater son of David (Mashiach ben David). After all, this was the great Zionist ideal repeatedly envisioned by the Hebrew prophets. One day God would send the Messiah to destroy Israel's enemies and establish His Kingdom (i.e., Temple) upon the earth. Israel would be exalted above the oppressive nations and universal peace would finally reign. The lion would lay down with the lamb and God would wipe away all tears of mourning. The words of the prophets would finally be fulfilled and Jerusalem would become the centerpiece of the entire world. Even some of Yeshua's own disciples attached great significance to the Temple and could not understand why Yeshua later abandoned it altogether (Matt. 23:37-24:2).

But notice that it was precisely at this time - during the Feast of Dedication - that Yeshua chose to collide with this popular, idealized, and nationalistic Messianic expectation. We must remember that Yeshua did not come to establish the Kingdom of God before He came to save a remnant of people who would be able to inherit it. Messiah ben Yosef, the great Suffering Servant, must precede Messiah ben David, the reigning King of Israel, and that, of course, meant that Yeshua first came to die as an atoning sacrifice for His people. How could there be a kingdom without true subjects? Or what good would there be to be a King without a kingdom? But in order to have a kingdom, the heart must be transformed and human nature regenerated by the power of the Holy Spirit. Yeshua was born to die, and His sacrifice was the doorway into the Kingdom of God....

To better understand Yeshua's "Chanukah Sermon" delivered to the zealots at the Temple, it is good to review some of the context given in John's gospel. Earlier in the year Yeshua had offered "Living Water" (מַיִם חַיִּים) to the Jews during the festival of Sukkot (John 7:37-44). While in Jerusalem, Yeshua went to the Temple (on the Sabbath) and forgave the woman taken in adultery. He then announced that He was the Light of the World (John 8:1-12). When challenged by the religious authorities, Yeshua stated that the validity of his claims were established through His Father (John 8:13-30) and he went on to plainly state His preexistence (John 8:52-59). As He left the Temple, Yeshua authenticated his message by healing a man who was blind from birth (John 9). He then began openly teaching that He was the Good Shepherd who would "lay down his life for his sheep" (John 10:1-18). The reaction of the crowd was mixed: "There was again a division among the Jews because of these words. Many of them said, "He has a demon, and is insane; why listen to him?" Others said, "These are not the words of one who is oppressed by a demon. Can a demon open the eyes of the blind?" (John 10:19-21).

It is at this point that John tells us that "at that time the Feast of Dedication took place at Jerusalem. It was winter, and Jesus was walking in the temple, in the colonnade of Solomon. So the Jews gathered around him and said to him, "How long will you keep us in suspense? If you are the Christ, tell us plainly" (John 10:22-24). In light of Yeshua's earlier teaching to the Jews, it is not surprising to hear his reply: "I told you, but you do not believe" (John 10:25). He then went on to say that the works He did in His Father's Name born witness about His identity, but they could not believe, since they were not part of God's flock. Only God's sheep can hear the voice of the Good Shepherd, and only they are able to follow Him: "My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me. I give them eternal life, and they will never perish, and no one will snatch them out of my hand. My Father, who has given them Me, is greater than all, and no one is able to snatch them out of the Father's hand. I and the Father are one" (John 10:27-30). Upon hearing this, the Jews wanted to stone Yeshua for blasphemy, since they rightly understood Yeshua's claim to be divine: "It is not for a good work that we are going to stone you but for blasphemy, because you, being a man, make yourself God" (John 10:33).

To the zealot, Chanukah meant the Messianic vision would be fulfilled, by violence if necessary. The heroic exploits of the Maccabees and their miraculous victory over the Syrians foreshadowed a greater battle to come (perhaps against the Romans), when Messiah, the son of David, would finally overthrown the enemies of Israel and establish the kingdom of God upon the earth. And yet it was precisely at this time that Yeshua stated that his works attested that he was indeed the Messiah of the Jewish people (John 10:37-38). Yeshua's earlier message that He was the "Good Shepherd" who would lay down His life for the sheep fell on deaf ears. The Zealot's hardness of heart proved that were not genuinely seeking the kingdom of God but instead had some other agenda. Only those who were truly God's people (i.e., "sheep") received the message of Yeshua and chose to follow Him. Instead of overcoming evil with evil, Yeshua would overcome evil with God's sacrificial love, laying his life down for the sheep as the promised Lamb of God, so that they could become inheritors of God's eternal kingdom... The way to overcome the world was through the truth about God's sacrificial love, not through the instruments of carnal warfare or through vain ideas of Jewish supremacy. Yeshua's message wasn't the answer the zealots wanted to hear, but it was the answer they needed to hear.

So what, if anything, does this imply about the follower of Yeshua and the holiday of Chanukah? Should Christians celebrate this festival, or should they reject it because it is generally associated with Jewish nationalism (and later rabbinical tradition)?

Well, first it's important to remember that had God not given the victory to the Maccabees, then the Temple would have been razed and Jewish identity would have been lost. Worse yet, Jewish assimilation into Greek culture might have jeopardized the coming of the Messiah Himself. Yeshua's disagreement with the zealots therefore concerned the spiritual meaning of the Temple (and how God could finally establish it upon the earth), but we should not regard this disagreement to imply that he negated the validity of Jewish historical experience - much less the words of the ancient prophets themselves. Indeed one day God would establish Zion upon the earth, but that would come about by the power of God, not by man (Acts 1:7). Just as Daniel prophesied about how the Messiah Himself would be "cut off" for the transgression of God's people (Dan. 9:24-27), so he foresaw the ultimate doom of the Antichrist by the hand of the Messiah Himself (Dan. 8:23-25). Yeshua likewise taught that the "little horn" (i.e., Antiochus) prefigured the greater "Abomination that makes Desolation" to come (Matt. 24:15-22, Mark 13:14; cp. Dan. 9:27, 11:31;12:11). Yeshua was of course speaking centuries after Antiochus set up an altar to Zeus and offered a pig in the Temple, and therefore it is clear that He was prophesying of a future "abomination that makes desolation" that would occur later in Jewish history. The Apostle Paul likewise stated "that day will not come, unless the rebellion comes first, and the man of lawlessness is revealed, the son of destruction, who opposes and exalts himself against every so-called god or object of worship, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, proclaiming himself to be God, who opposes and exalts himself against every so-called god or object of worship, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, proclaiming himself to be God" (2 Thess. 2:3-4).

Secondly, as I've stated in my Christmas article, it is likely that Yeshua was born during the festival of Sukkot (in the middle of the seventh month), when God chose to "tabernacle" with us (Immanuel), and this implies that Yeshua would have been conceived nine months earlier, during the season of Chanukah. (Put the other way around, if Yeshua were conceived in late Kislev (Nov/Dec), he would have been born 40 weeks later during Sukkot.) Chanukah then would commemorate the miracle of the Incarnation -- when God the Son chose to divest Himself of his regal glory to begin his redemptive advent into this dark world -- an event which undoubtedly is the among the most significant in all of sacred history.... It was by means of this advent, after all, that the Messiah would ultimately restore the Temple by means of His sacrificial life and death. In other words, since Yeshua was born during Sukkot, and conceived during Chanukah, celebrating this season can help us witness to the Jewish people that Yeshua is the true light of the world. The conception of the Messiah marked the beginning of the Redemption of Israel - and indeed the redemption of the entire world.

The Apostle John wrote of Yeshua: "The light shines in the darkness, but the darkness could not overcome it" (John 1:5). Recently I mentioned that the month of Kislev (כִּסְלֵו) is one of the "darkest" of the Jewish year, with the days progressively getting shorter and the nights getting longer. Indeed, the Winter Solstice generally occurs during the last week of Kislev, and therefore the week of Chanukah (which straddles the months of Kislev and Tevet) often contains the longest night of the year (even during "leap years," when the solstice occurs a bit later, there is always a new moon (i.e., the absence of moonlight) during the season of Chanukah). If Yeshua was indeed born during Sukkot (i.e., "Tabernacles"), then He was conceived during Chanukah - perhaps near the Winter Solstice itself. The true light - that enlightens everyone - would begin to shine during the darkest night of this world (John 1:9; 1 John 2:8). It is no wonder then that Chanukah represents an appropriate time to kindle the lights of faith....

זָרַח בַּחשֶׁךְ אוֹר לַיְשָׁרִים חַנּוּן וְרַחוּם וְצַדִּיק

za·rach ba·cho·shekh or lai·sha·rim, chan·nun ve·ra·chum ve·tzad·dik

"Light dawns in the darkness for the upright;

He is gracious, merciful, and righteous" (Psalm 112:4)

During Chanukah we always read about the Jacob's son Joseph and the outworking of his dreams. Indeed, the entire month of Kislev is sometimes called the "month of dreams" because the weekly Torah portions for this month contain more dreams than any other. No less than nine dreams (of ten in the Torah) appear in the portions of Vayetzei, Vayeshev, and Miketz - all of which are read during the month of Kislev. In the Torah, the primary figure connected with dreams is Joseph, who was nicknamed by his brothers as "that dreamer" and who was later named "Decipherer of Secrets" (Tzofnat Paneach) by Pharaoh (Gen. 41:45). Joseph was able to mediate the spiritual and the physical realms through the Spirit of God within him (Gen. 41:38). Prophetically Joseph represents Yeshua the "disguised Egyptian" who likewise was rejected and hated by his brothers - but who later became their Savior (for more on this, see "Mashiach ben Yosef"). Could it be providential "coincidence" that the Torah portion for Chanukah (Vayeshev or Miketz) always centers on Joseph - and therefore on the Messiah Yeshua?

Some of the sages have said the word Messiah (i.e., mashiach: מָשִׁיחַ) should be regarded as an acronym for the phrase: Madlikin (מ) Shemonah (שׁ) Yemei (י) Chanukah (ח), i.e., "we light throughout the eight days of Chanukah." During the eight days of Chanukah we kindle lights in commemoration of the "miracles, deliverance, mighty deeds salvations, wonders and solace" that our Heavenly Father performed for us "in those days, at this time" -- and this is thought to prefigure the greater deliverance to come in the power of the Messiah. Kindling the lights of Chanukah, then, recalls God's victory over Antiochus ("Epiphanes") but it also looks forward God's victory over the Antichrist in acharit hayamim (the period of the Great Tribulation during the End of Days). For more on this subject, see the article "Chanukah and Spiritual Warfare."

Finally, the "spirit of Chanukah" agrees with other teaching of the New Testament. The word chanukah (חֲנֻכָּה) itself means "dedication," a word that shares the same root as the Hebrew the word chinukh (חִנּוּךְ), meaning "education." Just as the Maccabees fought and died for the sake of Torah truth, so we must wage war within ourselves and break the stronghold of apathy and indifference that the present world system engenders (Rom. 12:2; Eph. 6:11-18). We must take time to educate ourselves by studying the Torah and New Testament, for by so doing we will be rededicated to the service of the truth and enabled to resist assimilation into the corrupt world. "Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world..." (1 John 2:15). The "cleansing of the Temple" is a matter of the heart, chaverim. The enemy is apathy and the unbelief it induces. We are called to "fight the good fight of faith" and not to conform to this present age with its seductions and compromises (1 Tim. 6:12, Rom. 12:2). The LORD Yeshua gives us light, the very "light of life." The light of the truth is the light of God's word (Psalm 119:105,130). God gives us the victory through the Spirit of Truth (רוּחַ הָאֱמֶת) since it is the love of the truth that brings us to salvation (2 Thess. 2:10-12). What does this mean to you who claim to know Yeshua and His message? How does this impact you as His follower in this darkened age?

קוּמִי אוֹרִי כִּי בָא אוֹרֵךְ וּכְבוֹד יהוה עָלַיִךְ זָרָח

ku·mi o·ri ki va or·rekh, ukh·vod Adonai a·la·yikh za·rach

"Arise, shine, for your light has come,

and the glory of the LORD has risen upon you."

(Isa. 60:1)

Study Card

The basic message of Chanukah is eschatological and full of hope. This evil world is passing away and one day the Kingdom of Heaven will be established upon the earth. We live in light of this blessed hope (Titus 2:11-13). The world's rulers are "on notice" from God Almighty: their days are numbered and they will surely face the judgment of the LORD God of Israel (Psalm 2). We must stand against the devil by refusing to conform to the world around us (Eph. 6:11-18). Now is the time. "Let your light so shine before others that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven" (Matt. 5:16). Followers of Yeshua are part of His Temple - members of His Body - and during this season we should heed the call to rededicate our lives to Him.

So let us celebrate the true Light of the World, Yeshua our beloved Savior and Messiah! Let your light shine, chaverim! Let's put away the sin that so easily besets us in rededication to our risen LORD. Chag Chanukah Sameach (חַג חֲנֻכָּה שָׂמֵחַ)! Light the candles in His honor, recite the blessings, sing some songs, pray for God's help - and enjoy some latkes! It's a hopeful season, and its message is more important today than ever before.

|

|

Joseph and his brothers

[ The following provides some further discussion regarding this week's Torah reading (Miketz). Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

11.29.10 (Kislev 22, 5771) The Torah plainly states that Jacob loved Joseph (יוֹסֵף) more than all his other sons, since he was the son of his old age, and was the firstborn son (bechor) of his beloved wife Rachel (Gen. 37:3). Indeed, Jacob and Joseph shared a lot in common: Both had infertile mothers who had difficulty in childbirth (Rebekah and Rachel); both of their mothers bore two sons (Rebekah: Esau/Jacob; Rachel: Joseph/Benjamin); both were hated by their brothers, and perhaps most significantly, both had lost their mothers (Joseph was present when his mother died, whereas Jacob never saw his mother again after he fled from his brother Esau). Perhaps this explains why Jacob favored his son and gave him the ketonet passim (כְּתנֶת פַּסִּים), a full-sleeved robe or ornamental tunic that set him apart from his other sons, and perhaps this also explains Joseph's juvenile boasting about his "dreams of preeminence" over his brothers.... The story of Joseph is, among other things, a story about his dreams. As a young man, his dreams centered on himself, which led to his betrayal and fall; after being humbled in prison, he focused on the dreams of others, which led to his exaltation...

There is a lot of mystery surrounding the story of Joseph. Like his father who fled from the hatred of his brother, Joseph became a victim of his brothers' malice. After being betrayed and sold into slavery as a teenager, Joseph later seemed to abandon his family identity. He had no "Bethel" experience along the way, however. Indeed, upon his release from prison he was thoroughly "Egyptianized." He wore Egyptian clothes, spoke fluent Egyptian, married an Egyptian wife, assumed an Egyptian name, and named his firstborn son "Manasseh" (מְנַשֶּׁה), a word that comes from the verb nasah (נָשָׁה), meaning "to forget." It's clear that Joseph wanted to forget his past life. After all, despite his ascendancy in Egypt -- when he had the means to reconnect with his long-lost family (including his father and brother who were deceived into thinking he was dead) -- he did nothing to contact them. (For more on this topic, see "The Heart's Truth.")

The truth (ἀ+λήθεια, see below) cannot be forever forgotten, however. When his brothers finally reappeared in his life seeking help, it had been 22 long years since they had last seen him. Joseph was now forced to deal with his past life. But he played the part of a "stranger" and withheld his true identity... As part of his charade, Joseph bound and imprisoned Simeon (who, according to tradition was the brother who originally threw Joseph into the pit). It was then that the brothers remembered what they had done to Joseph when they betrayed him as a child. Here the Torah adds a detail not originally given in the story of Joseph's betrayal, namely, that the brothers had ignored Joseph's desperate cries for help (Gen. 42:21-24). Perhaps the shock of seeing their helpless brother Simeon bound before them reminded the brothers of the terrible pain they had once caused Joseph...

Joseph, of course, demanded that his brother Benjamin be brought from Canaan in order to validate the brothers' story. Benjamin, the last link to Jacob's deceased wife Rachel, had apparently taken Joseph's place as Jacob's favorite son, and Jacob was unwilling to part from him. The famine, however, forced the issue and Judah swore to his father to take personal and eternal responsibility for the welfare of his beloved son... Jacob relented in a state of fearful resignation.

Although the sages argue about the exact chronology, it is clear that Benjamin was not a child when Joseph was thrown into the pit at age 17. When he finally saw his brother again, Joseph was so overcome with emotion that he left the room to weep. A midrash tells of the conversation between Joseph and Benjamin that brought tears to Joseph's eyes. Joseph asked Benjamin, "Have you a full brother, one who has the same mother as you?" "I had a brother," answered Benjamin, "but I do not know where he is." "Do you have sons?" asked Joseph. "I have ten." "What are there names?" "I named them all after my brother and the troubles that befell him. One is called Bela because my brother was nivlah - swallowed up - and disappeared. Another is called Bechor because he was the bechor (firstborn) of his mother. A third is called Achi because he was achi, my brother, and a fourth is called Chuppim because he did not see my chuppah (i.e., wedding day)." So Benjamin explained the names of his ten sons and Joseph was full of love for his brother and sadness for the time they had not shared together.

Another midrash tells the story about how Joseph seated his brothers from youngest to oldest (Gen. 43:33). He wanted to have Benjamin sit next to him but was unsure how to arrange the seating. Picking up his goblet and pretending that it had magic powers, Joseph called out the brothers names: "Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah," and so on from oldest to youngest. When he came to Benjamin, he said, "He has no mother and neither do I. He had a brother who was separated from him at birth, and so did I -- let him sit next to me!" The fivefold portion given to Benjamin was meant to test the brothers to see how they would react to a brother being shown preferential treatment.

When Joseph later framed Benjamin for stealing the "divination goblet," he was masterfully recreating a situation similar to the one in which he was sold by his brothers. Had they changed? Would his brothers abandon Benjamin as they had abandoned him in his hour of need? In order for there to be genuine reconciliation, Joseph needed to see if his brothers had really undergone teshuvah. When Judah stepped forward to take the place of his brother, he willingly accepted the guilt of them all. When Judah said, "What can we say, my lord; God has found out our sin" (Gen. 44:16), he was not confessing to the theft of the divination cup, but rather to the brothers' crime of throwing Joseph into the pit and selling him as a slave....

The word "Miketz" means "at the end of" and points to prophetic future (i.e., the "end of days" or acharit ha-yamim). Just as Joseph was a "dreamer" who was betrayed by his brothers but was promoted to a place of glory by the hidden hand of God, so Yeshua was betrayed by his people yet was exalted over all the nations (מֶלֶךְ הַגּוֹיִם). And just as Joseph later disguised himself as a "stranger" and an "Egyptian" to his brothers but was finally revealed to be their savior, so will the Jewish people come to see that Yeshua is the true Savior of Israel. Then will come true the hope of Rav Sha'ul (the Apostle Paul) who wrote, "And so all Israel shall be saved: as it is written, There shall come out of Zion the Deliverer who shall turn away ungodliness from Jacob" (Rom. 11:30).

May that hour come speedily, and in our days....

|

Parashat Miketz - מקץ

[ Note: Chanukah runs from Wednesday Dec. 1st (i.e., Kislev 25) through Thursday, Dec. 9th this year. The weekly Torah reading is not suspended for Chanukah (as it is for Passover and Sukkot), though additional Torah readings are read for each of the eight days of the holiday. ]

11.28.10 (Kislev 21, 5771) The Torah reading for this coming Shabbat (which occurs on the third day of Chanukah) is parashat Miketz. As this portion opens, Jacob's favored son Joseph had been languishing in prison for 12 years, but the appointed time had finally arrived for him to fulfill the dreams given to him as a young man. In this connection, I list some of the ways that Joseph is a "type" or foreshadowing of the coming Yeshua as the Suffering Servant (see "Mashiach ben Yosef"). The revelation of Joseph and his reconciliation with his brothers is a prophetic picture of acharit ha-yamim (the "End of Days") when Israel, in Great Tribulation, will come to Yeshua as Israel's deliverer. Presently, the veil is still over the eyes of the Jewish people and they collectively regard Yeshua as an "Egyptian" of sorts. For more information, please see the summary page for Miketz.

Note: If it pleases God I will add some additional commentary to parashat Miketz later this week. Meanwhile Happy Chanukah and blessings to you, chaverim.

|

Judah and Tamar

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Parashat Vayeshev. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

11.26.10 (Kislev 19, 5771) This week's Torah portion includes the rather unseemly account of Judah's union with his Canaanite daughter-in-law, Tamar (תָּמָר). The various Jewish commentators wondered why this narrative was inserted into the midst of the story of Joseph and his brothers. After all, the continuity of the Joseph story is clearly seen by simply skipping over chapter 38, so the question naturally arises as to why the story of Judah and Tamar was parenthetically placed here in the Torah portion. According to the Malbim, the story of Judah represents the axiom that "God creates the cure before the plague." Since the sale of Joseph led to the Egyptian exile (which is considered the paradigm of all exiles), it was necessary to plant the roots of ultimate redemption before the exile began. Thus before the "new Pharaoh" was born who would enslave Israel, the line of the Messiah, Israel's Deliverer and Redeemer, was further determined.

The "planting of this seed" came about in an unusual way, however. Recall that Judah had married a Canaanite woman named Shua (שׁוּעַ) who bore him three sons: Er, Onan, and Shelach (Gen. 38:2-5). After the boys had grown up, Judah arranged a marriage between Tamar with his firstborn son (Gen. 38:6). Er, however, was "wicked" in the sight of the LORD and God put him to death (the Torah does not state the nature of his wickedness, though a midrash states that Er did not want Tamar to get pregnant in order to preserve her beauty). At any rate, according to the custom of "Levirate marriage" (yibbum), Judah commanded his son Onan to "perform the duty of the brother-in-law to her" by producing an heir on behalf of his deceased brother. Now while Onan agreed to marry Tamar, he deliberately practiced a form of "birth control" that prevented the birth of his brother's heir. For this reason, the LORD put him to death as well. Judah was now without an appointed heir, and the entire lineage of his tribe was at jeopardy. He was reluctant, however, to give his third son marry Tamar, since were he to die, the lineage of Judah might end with his own death (Gen. 38:11). Perhaps it was because of this fear that he (misleadingly) promised Tamar that he would give his remaining son to her only after he "came of age."

Time went by, and soon Tamar realized that Judah was not going to fulfill his promise to give his son Shelach in marriage to her. Sometime after the death of his wife Shua, Judah went to visit his friend Hirah the Adullamite to sheer sheep. Upon hearing this, Tamar disguised herself as a prostitute and seduced him while he was on the road to Timnah. From this illicit union Tamar bore twin boys (Zerach and Perez), and from the line of Perez (פָּרֶץ, lit. "bursting forth" or "breakthrough") would descend King David - and ultimately Yeshua our Messiah Himself...

King David's genealogy not only included Abraham/Sarah, Isaac/Rebakah and Jacob/Leah, of course, but it also included Judah/Tamar, Boaz/Ruth, and Salmon/Rahab. It is interesting to note that in the genealogy of Yeshua given in Matthew (1:1-16), only four women (besides Mary) are explicitly named: Tamar (who seduced her father-in-law), Rahab (a prostitute), Ruth (a Moabitess), and "the wife of Uriah" (i.e., Bathsheba, an adulteress). Here is a (very simplified) diagram I made to indicate some of the relationships:

|

And now for your Torah question of the day: What spiritual characteristic(s) do you think united these four women? (see Ruth 1:16; 4:12; 1 Kings 1:13-31; Heb. 11:31; James 2:25). The blessing given to Boaz, "May your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah, because of the offspring that the Lord will give you by this young woman" (Ruth 4:12), suggests that God's plan of blessing providentially overcame the weakness and frailty of all the people involved... It is encouraging, is it not, that no matter what your personal background, God can use you to accomplish His will... Praise the LORD that His salvation "burst forth"!

Note: I am presently quite sick with a flu/cold. Your prayers for my healing are sincerely appreciated. Shabbat Shalom, chaverim!

Shabbat "Table Talk" Page - Vayeshev

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Parashat Vayeshev. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

11.26.10 (Kislev 19, 5771) It's an old custom to discuss the weekly Torah portion with your family (and friends) during the Friday night Sabbath meal. To make it a little easier to remember what to discuss, I created a "Shabbat Table Talk" page for parashat Vayeshev. Hopefully this will help to generate some discussion around your Sabbath table, chaverim. To download the page, click here.

Thanksgiving to God...

11.25.10 (Kislev 18, 5771) Shalom, chaverim. Since today is Thanksgiving Day, I thought I would share a Hebrew verse of praise with you here:

הוֹדִינוּ לְּךָ אֱלהִים הוֹדִינוּ וְקָרוֹב שְׁמֶךָ

סִפְּרוּ נִפְלְאוֹתֶיךָ׃

ho·di·nu le·kha E·lo·him, ho·di·nu ve·ka·rov she·me·kha,

sip·pe·ru ni·fle·o·te·kha

"We give thanks to You, O God; we give thanks, for Your Name is near.

We recount your wondrous deeds" (Psalm 75:1)

Download Study Card

We give thanks to God because He has graciously given us salvation (יְשׁוּעָה) through His Son Yeshua: for His Name is near. The adverb "near" (i.e., karov: קָרְבָּן) means "close enough to touch," and indeed the noun form means "a near kinsman." Because of Yeshua, God Himself has become our "close relative." Confession (i.e., todah: תּוֹדָה) and trust (i.e., emunah: אֱמוּנָה) are central here. As it is written: "The word is very near you [כִּי־קָרוֹב אֵלֶיךָ הַדָּבָר מְאד] - as close as your mouth and your heart (Deut. 30:14). You must confess with your mouth and believe "in your heart" that God loves you with an "everlasting love." Whoever calls upon the Name of the LORD will be saved (Joel 2:32; Acts 2:21; Rom. 10:9-13; Psalms 86:5; Rev. 3:20).

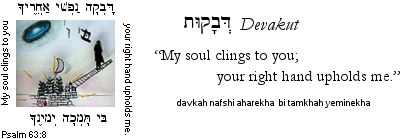

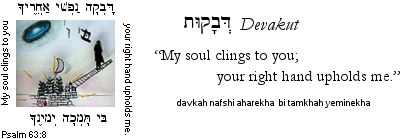

וְיֵשׁ אהֵב דָּבֵק מֵאָח

ve·yesh o·hev da·vek me·ach

"There is a lover who sticks closer than a brother"

(Prov. 18:24b)

The Scriptures repeatedly state that the LORD desires to "cleave" to our hearts in a loving relationship. יֵשׁ אהֵב דָּבֵק מֵאָח -- yesh ohev davek me'ach -- "there is a lover who sticks (davek) closer than a brother" (Prov. 18:24). The word translated "sticks" (דָּבֵק) comes from the Hebrew word davak (דבק), a word used elsewhere to describe how a man cleaves to his wife so that they become basar echad – "one flesh" (see Gen. 2:24). Davak is also related to the word for bodily joint (debek), suggesting that we are to stick as closely to the LORD as our bones stick to our skin (Job 19:20). The devakim (הַדְּבֵקִים) were those who "held fast" or "cleaved" to the LORD throughout the wilderness wanderings (Deut. 4:4), and all of us are likewise commanded to revere the LORD and cleave to Him (Deut. 10:20).

|

Our salvation means that we abide in a love relationship with the LORD God of Israel... "There is a lover who cleaves closer to a brother..." His Name is Yeshua, the true Lover of our souls... He is the greatest reason of all for us to give thanks to God today - and forever!

Note: I've been sick the last few days and was unable to attend a Thanksgiving celebration today (I have a bad cold/cough). I am thankful to the LORD for His steadfast love and grace to us all, however, and I am especially thankful for the friends of this ministry... Please accept my wishes for a Happy Thanksgiving to you and your family. Thank you for standing with us and helping make this ministry possible.... Shalom.

Light that cannot be hidden

[ The following entry concerns some thoughts about Chanukah, which begins Wednesday, December 1st at sundown this year.... ]

11.24.10 (Kislev 17, 5771) In the Gospel of John it is recorded that Yeshua said, "I am the way, the truth, and the life" (i.e., ᾽Εγώ εἰμι ἡ ὁδὸς καὶ ἡ ἀλήθεια καὶ ἡ ζωή). The Greek word translated "truth" in this verse is aletheia (ἀλήθεια), a compound word formed from an alpha prefix (α-) meaning "not," and lethei (λήθη), meaning "forgetfulness." (In Greek mythology, the "waters of Lethe" induced a state of oblivion or forgetfulness.) Truth is therefore a kind of "remembering" something forgotten, or a recollecting of what is essentially real. Etymologically, the word aletheia suggests that truth is also "unforgettable" (i.e., not lethei), that is, it has its own inherent and irresistible "witness" to reality. People may lie to themselves, but ultimately the truth has the final word... "The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it" (John 1:5).

Greek scholars note that the word lethei itself is derived from the verb lanthano (λανθάνω), which means "to be hidden," so the general idea is that a-letheia (i.e., truth) is non-concealment, non-hiddenness, or (put positively) revelation or disclosure. Thus the word of Yeshua - His message, logos (λόγος), revelation, and presence - is both "unforgettable" and irrepressible. Yeshua is the Unforgettable One that has been manifest as the express Word of God (דְּבַר הָאֱלהִים). Yeshua is the Light of the world (אוֹר הָעוֹלָם) and the one who gives us the "light of life" (John 8:12). Though God's message can be supressed by evil and darkened thinking, the truth is regarded as self-evident and full of intuitive validation (see Rom. 1:18-21).

The Hebrew word for truth (i.e., emet: אֱמֶת) comes from a verb (aman) that means to "support" or "make firm." There are a number of derived nouns that connote the sense of reliability or assurance (e.g., pillars of support). The noun emunah (i.e, אֱמוּנָה, "faithfulness" or "trustworthiness") comes from this root, as does the word for the "faithful ones" (אֱמוּנִים) who are "established" in God's way (Psalm 12:1). A play on words regarding truth occurs in the prophet Isaiah: אִם לא תַאֲמִינוּ כִּי לא תֵאָמֵנוּ / im lo ta'aminu, ki lo tei'amenu: "If you are not firm in faith, you will not be firm at all" (Isa. 7:9; see Faith Establishes the Sign). Without trust in the LORD, there is no stability... Truth is something trustworthy, reliable, firm, or sure. In colloquial English, for example, this idea is conveyed when we say, "He's a true friend...", indicating that the loyalty and love of the person is certain. The familiar word "amen" likewise comes from this root. Speaking the truth (dibbur emet) is considered foundational to moral life: "Speak the truth (דַּבְּרוּ אֱמֶת) to one another; render true and perfect justice in your gates" (Zech. 8:16). Yeshua repeatedly said, "Amen, Amen I say to you...." throughout his teaching ministry to stress the reliability and certainty of God's truth (Matt. 5:18, 26, etc.). Indeed, Yeshua is called "the Amen, the faithful and true witness" (Rev. 3:14).

The relationship between the Hebrew and the Greek ideas seems to be that the revelation of God - the aletheia - is reliable and strong. The source for all truth in the world is found in the Person and character of the LORD God of Israel... The self-disclosure of the LORD is both unforgettable - both in the factual and moral sense - as well as entirely trustworthy. Aletheia implies that truth is something that should never be forgotten. Hence we are regularly commanded and encouraged not to "forget" the LORD (Deut. 8:11, Psalm 103:2, etc.), to "remember" his covenants, to "keep" his ways, and so on. We are commanded to remember the light of God's revelation in our lives...

During this Chanukah Season -- and always -- may the LORD God of Israel help us walk in the unforgettable and irrepressible radiance of His glory. May God help us shine with good works that glorify God's Name (Matt. 5:16). "For God, who said, 'Let light shine out of darkness,' has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Yeshua the Messiah" (2 Cor. 4:6).

|

|

Chanukah and Spiritual Warfare

[ The following entry concerns some thoughts about Chanukah, which begins Wednesday, December 1st at sundown this year.... ]

11.24.10 (Kislev 17, 5771) CHANUKAH IS A STORY ABOUT REMAINING COMMITTED to the truth in a godless, and therefore insane, world. After all, since ultimate reality is the "handiwork" (i.e., conscious design) of a single, all-powerful, all-knowing, all-loving, morally perfect, purposive, personal, and spiritual Agency that has been revealed in the Jewish Scriptures, those who deny this Reality are living in a state of delusion (that is, a protracted "hallucination" that indicates radical departure from what is real). In a sense, the history of humanity - especially as it has been expressed philosophically and politically -- has been nothing less than the conscious collusion to redefine reality as something that it isn't. "The kings of the earth station themselves, and the dignitaries (רוֹזְנִים) take counsel together against (lit. "over") the LORD and His Mashiach" (Psalm 2:1-3). Spiritual warfare is therefore the fight for sanity and truth in a world that prefers madness and self-deception.

Despite being an anti-Semite, the early Church father Tertullian (160-220 AD) once asked a very good question: "What does Athens have to do with Jerusalem?" He was right for asking the question, though ironically, as a Greek-minded "replacement theologian," he was wrong for categorically libeling the Jewish people (see Adversus Iudaeos, c. 200 AD). Historically speaking, religious Jews have always loved the Torah and resisted the pull toward assimilation... Indeed, what other nation has survived over the millennia as have the Jewish people? Sadly, it is a continuing sin of many of today's "church leaders" to disregard the miraculous existence of Israel - including the modern State of Israel - by refusing to give the LORD God of Israel glory for His faithfulness.... Look, if God isn't faithful to the promises made to ethnic Israel, what makes these people think He won't change His mind regarding the Church? But I digress here...

Historically, Chanukah remembers the Maccabee's resistance to the forced Hellenization (i.e., the spread of pagan Greek culture) of the Jewish people, though more generally it represents the ongoing struggle against assimilation to the prevailing "world system." In modern day America, for instance, the pressure to assimilate takes the form of "political correctness" and the acceptance of official propaganda that multicultural pluralism/cultural relativism is the truth. For those of us who follow Yeshua, Chanukah is the bold proclamation that the Light of the World has come, despite the face that "people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil" (see John 3:19).

The story of Chanukah goes back to ancient Greece and the pagan worldviews of Hesoid and Homer, Plato and Aristotle. Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BC), the tutelage of Aristotle, became a militant King of Macedon who swept across Syria, Egypt, and Babylonia to defeat the mighty Persian Empire. Alexander's rapid military conquests extended Greek culture and influence throughout the civilized world. When he later died (323 BC), Alexander's kingdom was divided into four parts and the land of Israel became a province of Syria under the rule of the Seleucid dynasty.

In 175 BC, a new king, Antiochus IV (also called "Epihpanes") ascended the throne in Syria. Under the "auspices" of his regime, Jerusalem began to look more and more like a Greek city as Hellenistic culture was officially promoted. Antiochus allowed Hellenistic Jews to have prominent roles in the Holy Temple - so much so that even a non-priest (named Menelaus) was given the role of being the Temple's Kohen Gadol (High Priest). This enraged many Jews, however, who then called for Egyptian rule instead of Syrian (the Egyptians were more tolerant of local customs and did not force Hellenization). Later, when Antiochus returned from an unsuccessful military campaign against Egypt, he decided to quell the Jewish call for Egyptian rule and murdered some 40,000 people in Jerusalem. Soon after this, he decreed that Jews must abandon their faith in the Torah and to cease offering sacrifices in the Temple. The Holy Temple itself was desecrated and images of the god of Zeus (the "sky god") were placed on the altar and in the sanctuary. Pagan altars were soon erected throughout Judea and pigs were regularly sacrificed upon them. The study of Torah was outlawed (as well as the observance of Shabbat, holidays, and ritual circumcision), and the penalty for disobedience to these decrees was death.

Many Jews fled and hid in the wilderness and caves and many died kiddush HaShem - as martyrs (see Heb. 11:36-39). Eventually Jewish resistance to this imposed Hellenization meant literal war. In 164 BC, in Modin, a small town about 17 miles from Jerusalem, Mattityahu (Matthias), a Hasmonean priest, and his five sons took refuge. When Antiochus' soldiers arrived at Modim to erect an altar to Zeus and force the sacrifice of a pig, Mattityahu and his sons rose up and killed the Syrians. They then fled to the Judean wilderness and were joined by other freedom fighters. After some organizing, they soon engaged in successful guerrilla warfare against their Syrian/Greek oppressors.

Mattityahu died about a year later and his son Judah became the leader of the resistance. Judah came to be known as the "Maccabee" -- a title that either was an acronym of the phrase, mi komocha ba'elim Adonai, "Who is like You among the gods, LORD?" (Exod. 15:11) or else was derived from the Hebrew word for "hammer" (makevet), indicating his ferocity in battle. According to legend (Shabbat 21b), on the 25th of Kislev, three years to the day after the Syrian/Greeks had defiled the Holy Temple by making it a shrine to Zeus, the Maccabees vanquished their oppressors and recaptured the Temple. When the faithful Jewish priests searched for the holy olive oil to light the menorah, however, they found only one jar that was not defiled (i.e., only one still had the seal of the High Priest). The oil in this jar was sufficient to burn for only one day, and it would take eight days until a new supply could be produced. According to tradition, the one-day supply of oil miraculously burned in the menorah for eight days, and later, this eight day period was commemorated as Chunukah, "Dedication," also known as the Festival of Lights.

Interestingly, Chanukah is mentioned only a couple times in the Talmud (i.e., Shabbat 20a, 21b), perhaps because the Maccabean dynasty (the forefathers of the Sadducees) eventually became entirely corrupt, and the Talmud (which grew out of Pharisaic tradition) did not want to draw much attention to them. Therefore the Talmud's statements (recorded centuries after the Maccabean rebellion) focus on the miracle of the oil rather than on the merits of the Maccabean resistance. This approach has been adopted in normative (rabbinical) Judaism, and today Chanukah primarily centers on the miracle of the lights (i.e., the lighting of the candles) rather than the militant overthrow of religious persecutors.

Chanukah is alluded to in the Torah itself. First, the 25th word of the Torah is or, "light," as in "Let there be light" (Gen. 1:3), and some of the sages say that this suggests Kislev 25. Second, immediately after the festivals (moedim) of the Jewish year are enumerated in Leviticus 23, the commandment to "bring clear oil from hand-crushed olives to keep the menorah burning constantly" is given (Lev. 24:1-2), and this is said to foresee the time of Chanukah.

Some Bible scholars say that the prophet Daniel foresaw the events of Chanukah centuries beforehand in a vision of a "male goat running from the west" with a conspicuous horn between its eyes (Alexander the Great) that was broken into four (Dan. 8:1-12). Out of the four horns arose a "little horn" (Antiochus) who greatly magnified itself, cast down some of the stars (righteous souls), took away the sacrifices, and cast down the sanctuary in Jerusalem. Years after the Maccabean revolt, Yeshua celebrated Chanukah in the same Temple that had been cleansed and rededicated only a few generations earlier (John 10:22). It was here that many asked if He were the coming Messiah -- harkening back to the liberation of the earlier Maccabees. During a season of remembering miracles (nissim), Yeshua pointed out that the works that He did attested to His claim to be the long-awaited Mashiach of the Jewish people (John 10:37-38).

Finally, in an eschatological sense "Epihpanes" foreshadows the coming time of the "Messiah of Evil" (anti-christ) who will one day attempt to "assimilate" all of humanity into a "New World Order" (Dan. 9:27, 2 Thess. 2:3; Rev. 13:7-9, etc.). At first he will appear to be a "world savior" who will broker peace for Israel and the Mideast, but after awhile, like his archetype Epiphanes, he will savagely betray the Jewish people and set up a "desolating sacrilege" in the Holy Place of the Temple (Mattt. 24:15). His satanic rise will occur during acharit hayamim - the "End of Days" - otherwise called the period of the Great Tribulation (Matt. 24). The Final Victory of God will be established when Yeshua returns to destroy this Messiah of Evil at His Second Coming. The Holy Temple will then be rebuilt and dedicated by the hand of the true Mashiach of Israel...

Practically speaking, the word chanukah (חֲנֻכָּה) means "dedication," a word that shares the same root as the Hebrew the word chinukh (חִנּוּךְ), meaning "education." Just as the Maccabees fought and died for the sake of Torah truth, so we must wage war within ourselves and break the stronghold of apathy and indifference that the present world system engenders. We must take time to educate ourselves by studying the Torah and New Testament, for by so doing we will be rededicated to the service of the truth and enabled to resist assimilation into the corrupt world. Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world... (1 John 2:15). The "cleansing of the Temple" is a matter of the heart, chaverim. The enemy is apathy and the unbelief it induces. We are called to "fight the good fight of faith" and not to conform to this present age with its seductions and compromises (1 Tim. 6:12, Rom. 12:2).

Wishing you a joyful time of celebrating the overcoming victory of the Light of the World, chaverim (John 1:5).

|

The Beauty of God's Truth

[ The following entry concerns some thoughts about Chanukah, which begins Wednesday, December 1st at sundown this year.... ]

11.24.10 (Kislev 17, 5771) It has been said that the Greek mindset regards what is beautiful as what is good, whereas the Hebraic mindset regards what is good as what is beautiful. The difference is one of orientation. Doing our duty before God, in other words, is what is truly beautiful, not merely appreciating the appearance of symmetry, order, and so on. This explains why moral discipline (i.e., musar, מוּסָר) is so prominent in Hebrew wisdom literature. True beauty cannot exist apart from moral truth.

The word chinukh (חִנּוּךְ), "education," shares the same root as the word "chanukah" (חֲנֻכָּה, dedication). Unlike the Greek view that regards education as a pragmatic process of improving one's personal power or happiness, the Jewish idea implies dedication/direction to God and His concrete purposes on the earth. Disciples of Yeshua are likewise called talmidim (תַּלְמִידִים) -- a word that comes from lamad (לָמַד) meaning "to learn" (the Hebrew word for teacher is melamad (מְלַמֵּד) from the same root). In the New Testament, the word "disciple" is μαθητής, a learner or a pupil of a διδάσκαλος, or a teacher. True education is therefore foundational to being a disciple of the Mashiach.

(Note that the Hebrew word "rabbi" comes from the word rav (רַב), which means "great." The word rabbi (רִבִּי) is formed by adding the 1st person singular ending, i.e., "my great one," or "my reverend." In Yiddish the word is rebbe. Yeshua told us not to call anyone other than Him "rabbi" or "father" since we are all brothers and sisters and He alone is our Master (Matt. 23:8)).

Following Yeshua, then, first of all means submitting to His authority and learning from Him as your Teacher (Matt. 23:8). Only after spending time with Him are you commissioned to go "to all the nations and teach..." (Matt. 28:19). This is accomplished not only by explaining (propositional) doctrine but by kiddush HaShem -- sanctifying the LORD in our lives. We are called to be a "living letter" sent to the world to be "read" (2 Cor. 3:2-3).

During Chanukah we recall the courage and faith of Judah the "Maccabee" and his brothers. The name "Maccabee" is said to be an acronym [מ כּ בּ י] for Moses' affirmation of faith: מִי־כָמכָה בָּאֵלִם יהוה / "Who is like you, LORD, among the mighty?" (Exod. 15:11). Since God alone is the Supreme Ruler of the universe, we do not need to live in fear of man. As King David wrote: יהוה אוֹרִי וְיִשְׁעִי מִמִּי אִירָא / "The LORD is my Light and my Salvation - of whom shall I be afraid?" (Psalm 27:1). Yeshua the Messiah is our true Light (ha'or ha'amiti) and our Salvation (yeshu'ah). He has said, "My peace I give unto you. Let not your heart be troubled; neither let it be afraid. In the world you shall have tribulation: but be of good cheer; I have overcome the world" (John 14:27, 16:33).

בָּרוּךְ הוּא הָאֱלהִים אֲשֶׁר נָתַן־לָנוּ תְּשׁוּעָה נִצַּחַת בְּיַד

יֵשׁוּעַ הַמָּשִׁיחַ אֲדנֵינוּ

barukh hu ha-Elohim asher natan-lanu teshuah nitzachat b'yad

Yeshua ha-Mashiach Adoneinu

Thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through

our Lord Yeshua the Messiah! (1 Cor. 15:57)

(Study Card Download)

Some of the Jewish sages said that "the seal of God is truth," since the final letters of the three words that conclude the account of creation: בָּרָא אֱלהִים לַעֲשׂוֹת / bara Elohim la'asot: "God created to do" (Gen. 2:3) -- spell the word for truth (i.e., emet, אֱמֶת):

|

In other words, God created reality "to do" (לַעֲשׂוֹת), which has come to be interpreted by these sages as meaning that it is our responsibility, as God's creatures, to participate in the "doing" of His work. Truth is about doing, not being; it is centered upon the realm of duty and obligation and is grounded in the mandate to "name" the creation.

Note that the "Seal of God" is not just a matter of sincerity. It is rather a matter of being true in the sense that you are living it, you are "being with it," you are part of it. Truth is a passion that informs all of the decisions you make in your life. You therefore embody the truth and follow it in all your endeavors. In this sense Yeshua the Messiah is the Truth, since in Him there was no mismatch between who He is and what He says. He is utterly trustworthy. His actions and speech are one and are entirely reliable. Yeshua is the "Seal of God," the one who authoritatively names of all creation, and His followers likewise should evidence this in their lives.

During this Chanukah Season -- and always -- may the LORD God of Israel help us shine the radiance of Yeshua in our daily lives (Matt. 5:16).

|

Getting Ready for Chanukah

[ Chanukah comes early this year! We will light the first candle on Wednesday, December 1st, after sundown... ]

11.24.10 (Kislev 17, 5771) The Hebrew word chanukah (חֲנֻכָּה) means "dedication" and marks an eight day winter celebration that commemorates the victory of faith over the ways of speculative reason, and demonstrates the power of the miracle in the face of mere humanism. Generally speaking, Chanukah is a "fighting holiday" -- a call to resist the oppression of this world and to rededicate our lives to the LORD (Rom. 12:1-2). This year Chanukah begins on Wednesday, December 1st at sundown (i.e., Kislev 25) and runs through Thursday, December 9th (i.e., Tevet 2).

Even though Thanksgiving Day is nearly here, we are getting some of our Chanukah decorations out of storage to begin preparing for the celebration next week. It's time to clean the chanukiahs, get some new candles, and plan for our Chanukah onegs. To help my family get into the mood, I strung some Christmas lights up in the kitchen and started playing some traditional Chanukah music (Maoz Tzur, the Dreidel Song, etc.). Judah is now 19 months old, and Josiah just turned six. Of course they are both very excited about the coming holiday. Here are a couple pictures I took of the boys yesterday:

|

During this Chanukah Season -- and always -- may the LORD God of Israel help us shine the radiance of Yeshua in our daily lives (Matt. 5:16).

Thanksgiving Day and Sukkot

11.23.10 (Kislev 16, 5771) The American Holiday of Thanksgiving certainly has its roots in the Jewish tradition of giving thanks to God, and some historians believe that the early "pilgrims" derived the idea directly from the Biblical festival of Sukkot (i.e., "Tabernacles"). According to some scholars, before coming to the New World, the pilgrims lived for a decade among the Sephardic Jews in Holland, since Holland was considered a safe haven from religious persecution at the time. Since the pilgrims were devout Calvinists and Puritans, their religious idealism led them to regard themselves as "new Israel," and it is likely that they learned that Sukkot commemorated Israel's deliverance from their religious persecution in ancient Egypt at that time. After they emigrated to the "Promised Land" of America, it is not surprising that the pilgrims may have chosen the festival of Sukkot as the paradigm for their own celebration. As the Torah commands: "[Celebrate the feast] so that your generations may know that I made the people of Israel dwell in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God" (Lev. 23:39-43). The highly religious pilgrims regarded their perilous journey to the new world as a type of "Exodus event" and therefore sought the appropriate Biblical holiday to commemorate their safe arrival in a land full of new promise...

Recall that during the holiday of Sukkot we are commanded to dwell in sukkahs to remind ourselves of the sheltering presence of God given to our ancestors in the wilderness. After the Jews finally began inheriting the land, the theme of Sukkot shifted to an expression of thanks for God's provision and steadfast love. In that sense, Sukkot is a sort of "Jewish Thanksgiving" celebration. During the fall harvest (traditionally called the "Season of our Joy") the Torah commands us to "rejoice before Adonai your God" (Deut. 16:11-15; Lev. 23:39-43). When we wave our lulavs (symbols of the fruit of the earth and the harvest), it is customary to recite the following expression of thanks:

הוֹדוּ לַיהוה כִּי־טוֹב כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ

ho·du la·Adonai ki tov, ki le·o·lam chas·do

"Give thanks to the LORD for He is good;

for His steadfast love endures forever."

Download Study Card

The Refrains of Praise

A basic principle in Bible interpretation is to note repeated occurrences of a word or phrase. This is sometimes called the "law of recurrence." The assumption here is that since God is the consummate Communicator, if a word or phrase is repeated in Scripture, there is surely a good reason. In some cases the function appears to be instructive (such as the two sets of instructions given for building the Mishkan (tabernacle) in Exodus); in other cases it appears to be exclamatory: the LORD doesn't repeat Himself without the intent of getting our attention.

But notice that the phrase, hodu la-donai ki-tov, ki le'olam chasdo ("Give thanks to the LORD for He is good, for His stedfast love endures forever") appears no less than five times in Scripture (1 Chr. 16:34; Psalm 106:1; Psalm 107:1; Psalm 118:1,29; Psalm 136:1), and in each case it is clear that the Holy Spirit is emphasizing that God's love for us -- His chesed -- is the primary reason for us to give Him thanks (in Psalm 136, the refrain, "ki le'olam chasdo" occurs no less than 25 times). Notice also that the verb hodu is the imperative of yadah (to confess or express gratitude) and therefore we can understand this verse to mean that we are to "confess" or "acknowledge" that the LORD is good. Indeed, the Hebrew word todah (תּוֹדָה), usually translated "thanks," can mean both "confession" and "praise."

A Thanksgiving Seder

Thanksgiving is perfectly compatible with Messianic Jewish observance, and since the holiday always falls on a Thursday there is never a conflict with Sabbath celebrations. You can create a simple "Thanksgiving Seder" by reciting Kiddush (the blessing over the wine and the bread) and then offering a special prayer of thanks before eating the meal. Everyone could recite the refrain: "Give thanks to the LORD, for He is good; His steadfast love endures forever" (see Hebrew text above). The "Shehecheyanu" blessing may then be recited to mark the occasion as spiritually significant:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ אֱלהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם

שֶׁהֶחֱיָנוּ וְקִיְּמָנוּ וְהִגִּיעָנוּ לַזְּמַן הַזֶּה

ba·ruch at·tah Adonai E·lo·hei·nu Me·lekh ha·o·lam

she·he·che·ya·nu ve·ki·ye·ma·nu ve·hig·gi·a·nu la·ze·man haz·zeh

"Blessed are You, LORD our God, Master of the Universe,

Who has kept us alive and sustained us and brought us to this season."

Download Study Card

During the meal, people might take some time to share their own experience of finding freedom in America or to discuss why they regard freedom as important. The connections between Passover (the Exodus), Shavuot (the Sinai and "Pentecost" experiences), Sukkot (God's care for Israel during their wanderings in the desert), and the American holiday of Thanksgiving would also make an excellent discussion. It is also interesting to note that the Hebrew word for "turkey" is tarnegol hodu (תַּרְנְגוֹל הוֹדו), literally, "Indian chicken," which is often shortened to hodu (הוֹדוּ). It is a happy coincidence that we customarily eat turkey on Thanksgiving, and this reminds us of the "thanks" connection: "Give thanks (hodu) to the LORD, for He is good; for His steadfast love endures forever."

Since Yeshua is the ultimate expression of God's steadfast love (i.e., chesed: חֶסֶד), how much more should we give heartfelt thanks to God for Him? Is there anything greater than the astounding love of God? Can anything overcome it? Can even the hardness of your own heart somehow veto or negate it's purposes? It was because of His great love that God (יהוה) "emptied Himself" of heavenly glory, becoming clothed in human flesh and becoming disguised a lowly slave (δοῦλος). God performed this act of "infinite condescension" in order to "tabernacle" with us as our "hidden King" (John 1:1,14, Phil. 2:7-8). Ultimately our thanks to God is our praise for Yeshua, our Savior, King, and LORD.

|

We wish you a joy-filled time of reflection during this Thanksgiving Holiday. May you remember the many blessings that the LORD God of Israel has lovingly bestowed upon you and your family.... Hodu La-Adonai!

Personal Update: I really could use your prayers, chaverim. I have been battling with feelings of sadness recently, and my chronic pain issues are ever-present. I am also suffering from a cold. Thank you so much...

Joseph and the Messiah

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Parashat Vayeshev. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

11.22.10 (Kislev 15, 5771) In the account of Joseph's betrayal and rejection by his brothers, we read: "And they took him and threw him into a pit. The pit was empty; there was no water in it" (Gen. 37:24). Rashi asked why the Torah says that there was no water in the well, since it was already described as being empty (i.e., reik: רֵק). Some of the sages suggest that the additional phrase ("there was no water in it") was meant to stress that there was nothing at all to sustain life where the brothers cast Joseph. The pit, in other words, symbolized a place of death and the return to the "dust of death." The redundancy implies that while there was no water in the pit, there were other things, such as serpents and scorpions... In other words, the lack of water was symbolic of the forces of evil.

Interestingly, the Hebrew word used to say that the well was "empty" can also mean vain. We see this usage, for example, in Psalm 2:1: "Why do the nations rage and the peoples plot in vain." Just as it was a vain plot by the brothers to do away with Joseph, so it is a vain plot of the rulers of this world to "take counsel together, against the LORD and against his Anointed (מְשִׁיחוֹ), saying 'Let us burst their bonds apart and cast away their cords from us'" (Psalm 2:2-3). The story of Joseph is a triumph of God's providential love that overcomes the plots of mankind's malice and the power of death itself. Just as Joseph was raised out of the pit and eventually exalted as Israel's savior, so the death, burial and resurrection of Yeshua the Messiah is the means by which all Israel - and indeed the entire world - will one day be saved. "Because of the blood of my covenant with you, I will set your prisoners free from the waterless pit" (Zech. 9:11).

Note: For a brief listing of no less than 48 ways that Joseph prefigures (or pictures) the Messiah Yeshua, see the article "Mashiach ben Yosef."

|

Parashat Vayeshev - וישב

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Parashat Vayeshev. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

11.21.10 (Kislev 14, 5771) From the beginning of this week's Torah portion (Vayeshev) until the end of Sefer Bereshit (the Book of Genesis), the focus shifts from Jacob to his twelve sons, but most especially to his beloved son Joseph (יוֹסֵף). What initially appears as a sequence of terrible hardships for Joseph finally results in the deliverance of the Jewish people during a time of great tribulation. The story of Joseph's ordeal is therefore the story of Divine Hashgachah (providential supervision) that also foretells the glory of the Messiah both as a suffering servant and as a national deliverer of Israel.

The Torah reading begins, "Jacob settled (vayeshev Ya'akov) in the land of his father's sojourning, in the land of Canaan" (Gen. 37:1), but then immediately turns to the story of Joseph, who was seventeen years old at the time: "And these were the generations of Jacob: Joseph being seventeen years old..." (Gen. 37:2). Why does the toldot (genealogy) of Jacob begin with Joseph rather than Reuben (the firstborn son of Leah) here? Was the Torah suggesting that Joseph was regarded by Jacob as his (chosen) "firstborn" son?

Jacob and Joseph undoubtedly shared a lot in common, and this surely caused Jacob to prefer his firstborn son (of Rachel) over his other sons. For instance, both men had infertile mothers who had difficulty in childbirth; both mothers bore two sons; and both were hated by their brothers. In addition, the Torah states that Jacob loved Joseph more than all his other sons since he was the son of his old age, and was the firstborn son (bechor) of his beloved wife Rachel. Indeed, Jacob made him an ornamented tunic (ketonet passim) to indicate his special status in the family.

At any rate, the Talmud (Sanhedrin 106a) notes that whenever the word vayeshev (וַיֵּשֶׁב) is mentioned in Torah, it introduces a painful episode. Immediately following the statement that "Jacob settled (vayeshev Ya'akov) in the land of his father's sojourning," the Torah states that Joseph brought an "evil report" about his brothers to his father. This act ultimately led to the selling of Joseph into slavery and to further heartache for Israel. The Jewish sage Rashi notes that whenever someone called by God wants to "settle down" and live at ease, God orchestrates events to keep him free from complacency. This certainly happened in the case of Jacob, where sibling rivalry and baseless hatred (called sinat chinam, (שִׂנְאַת חִנָּם)) so disrupted the peace of the family that his children were eventually led into exile and slavery.

Hebron (חֶבְרוֹן) is one of the very first places Abraham lived after he entered the Promised Land (Gen. 13:18). Some of the sages note that the "Valley of Hebron" (i.e., the place from which Jacob commissioned Joseph to go check on his brothers (Gen. 37:14)), should rather be translated as "from the depth of Hebron" (מֵעֵמֶק חֶבְרוֹן), suggesting that Joseph's assignment was the first step toward fulfilling the prophecy the LORD gave to Abraham of Israel's descent into Egypt (Gen. 15:13). The word Hebron comes from a root (ח.ב.ר) that means "association" or "union," suggesting that from the depths of the family union would come struggle but eventual deliverance.

Note: This year Chanukah begins on Wednesday, December 1st at sundown (1st candle) and runs through Thursday, December 9th.

|

Shabbat "Table Talk" Page - Vayishlach

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Parashat Vayishlach. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

11.19.10 (Kislev 12, 5771) It's an old custom to discuss the weekly Torah portion with your family (and friends) during the Friday night Sabbath meal. To make it a little easier to remember what to discuss, I created a "Shabbat Table Talk" page for parashat Vayishlach. Hopefully this will help to generate some discussion around your Sabbath table, chaverim. To download the page, click here.

Note: Please let me know if you like this idea, or if you have any additional suggestions to help make your family discussions of the Torah a bit easier.

Shabbat Shalom, chaverim!

The Tears of Rachel...

[ This week's Torah portion (Vayishlach) raises a number of interesting "open-ended" questions, and I try to consider a few of them here. At the end of this entry, I list some additional questions that I hope will prompt you to continue your study and exploration... Shalom, chaverim! ]

11.18.10 (Kislev 11, 5771) While Jacob was away from home in Paddan Aram (i.e., Charan), there is no indication that he ever checked on the welfare of his mother and father or otherwise attempted to contact them. He didn't invite them to his wedding(s); he didn't tell them about the birth of their grandchildren; and he didn't tell them about his toil under Laban... So why did he seem to disregard his parents? After all, his mother had advised him to flee to her brother's house in the first place (Gen. 27:43), and apparently Rebekah and Laban were on speaking terms (the midrash says that they had planned on marrying their children to one another). It certainly seems possible that Jacob could have relayed messages back home. So why didn't he do so?