|

October 2010 Updates

Parashat Toldot - תולדת

10.31.10 (Cheshvan 23, 5771) The Torah reading for this week is called Toldot ("generations"). This parashah is about Isaac and Rebekah's family and how the promised Seed (i.e., Messiah) would descend through Isaac's son Jacob (renamed Israel) -- rather than through his older twin brother Esau. From Israel (i.e., the Jewish people) would come the "generations" that would ultimately lead to the salvation of the world. As our beloved Yeshua (Jesus) said, "salvation is from the Jews" (John 4:22).

Note that during the dramatic episode of the "stolen blessing," some of the sages suggest that Isaac actually knew he was blessing Jacob, but "pretended" to be fooled in order to avoid destroying his relationship with his firstborn son Esau.... Isaac's blindness is central here: when he had his carnal sight, he favored Esau; when he lost it, he was able to bless Jacob...

I hope to add some additional commentary to this Torah portion later this week, chaverim.

The Month of Kislev

10.31.10 (Cheshvan 23, 5771) "Sunrise, sunset; swiftly go the days...." Sunday November 7th is "Rosh Chodesh Kislev" (ראש חדש כסלו), i.e., the "new moon" of the ninth Hebrew month of the Jewish calendar (counting from Nisan). The month of Kislev is unusual because it sometimes varies between 29 and 30 days on the Jewish calendar. Of course, Kislev is also the month when the eight day holiday of Chanukah (חנוכה) begins. This year Chanukah begins on Wednesday, December 1st at sundown (1st candle) and runs through Thursday, December 9th.

Considering these later days of autumn (and the "late hour" of human history), the following pasuk (verse) comes to mind:

יָבֵשׁ חָצִיר נָבֵל צִיץ וּדְבַר־אֱלהֵינוּ יָקוּם לְעוֹלָם

ya·veish cha·tzir na·veil tzitz; u'de·var E·lo·hei·nu ya·kum le·o·lam

"Grass withers, flowers fade, but the word of our God

stands forever" (Isa. 40:8)

Every time I check the news I am reminded that we are living in a "withered and fading world" -- the prophesied "End of Days" (אַחֲרִית הַיָּמִים). But Baruch Hashem: our place (מָקוֹם) is grounded in truth that stands (i.e., יָקוּם, "is raised up") forever! Yeshua is our life, chaverim.... He is the Word of our God that is raised up forever!

"Days of the Years"

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Chayei Sarah (the "life of Sarah"). Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

10.29.10 (Cheshvan 21, 5771) In our Torah portion this week we read about the death of Abraham, the original patriarch of the Jewish people and great hero of faith: "These are the days of the years of the life of Abraham, which he lived..." (וְאֵלֶּה יְמֵי שְׁנֵי־חַיֵּי אַבְרָהָם אֲשֶׁר־חָי) (Gen. 25:7). It is interesting to notice that this verse mentions Abraham's days but then goes on to state the number of years that he lived. Why, then, does the verse mention the word "days" at all? Moreover, the verse includes the seemingly redundant clause, "which he lived" (אֲשֶׁר־חָי), an addition that appears to be unnecessary to the meaning. Since the sages assumed that there were no unnecessary words revealed in the Torah, they wondered why the verse was written this way....

When we reckon a person's life span, we (objectively) refer to their physical longevity in terms of years. This is why we celebrate birthdays, after all, and that's why we refer to someone as being so many years old. Jewish tradition recognizes calendar years, of course (our verse states that Abraham lived 175 years), though the sages understood time primarily in terms of "length of days." When the patriarch Isaac died, for example, the Torah says he was "gathered to his people, old and full of days" (Gen. 35:29). The sages defined a day (yom) in terms of the total time of daylight (measured from sunrise to sunset), and defined an hour (sha'ah) by dividing that time into 12 equal parts (this is called sha'ah zemanit, or a "proportional hour"). Each proportionate hour was then divided into 1080 "parts" (called chalakim), and each part (chelek) was further divided into 76 "moments" (rega'im). In other words, the sages measured time by increasingly smaller units, and these days, hours, "parts," and moments were used to objectively measure time (interestingly, modern science likewise attempts to "divide time" down to smaller and smaller units, until it defines it as the length of time required for light to travel in a vacuum, i.e., "Planck time." In other words, space and time are known through observing light).

Life is surely more than a quantitative measurement of time, however. What good is a physically long life without a relationship with God? Is it not "vanity of vanities," a "tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing," as Shakespeare once said? Time finds its qualitative meaning, its purpose, and its direction only in relationship with God, who is the "beginning, the middle, and the end." Our personal histories likewise have a beginning, middle, and an end that together form a "story" about who we are.... Your life is "going somewhere," and each moment of your day is your means to that end. Each moment leads inexorably to the next, and together these moments form hours, days, and the "days of the years." Teshuvah (repentance) is a conscious choice to turn to God amidst the flux of passing time in order to awaken to the realm of the eternal. Therefore we see the greatest of the tzaddikim (such as Abraham) living out the "days of the years" in conscious awareness of eternity, and of his ultimate destination: "By faith Abraham obeyed when he was called to go out to a place that he was to receive as an inheritance. And he went out, not knowing where he was going. By faith he went to live in the land of promise, as in a foreign land, living in tents with Isaac and Jacob, heirs with him of the same promise. For he was looking forward to the city that has foundations, whose designer and builder is God" (Heb. 11:8-10). Faith affirms that underlying the "surface appearance" of fleeting life (olam hazeh) is a deeper reality that is ultimately real and abiding (olam habah). It "sees what is invisible" (2 Cor. 4:18) and understands (i.e., accepts) that the "present form of this world is passing away," like so many seconds ticked off a clock (1 Cor. 7:31).

Time is God's gift to us, as well as a test... The story is told about how a man once spied the Vilna Gaon sitting at a table in the evening, weeping over a small piece of paper he had pulled from his pocket. After he wiped away the tears, the Gaon got up and left the room, leaving the paper on the table. The man who oversaw this then went over to look at the piece of paper and saw just seven dots marked on it, nothing else. Overcome by curiosity, the following morning the man asked the Gaon what the paper meant and why it made him cry. The Gaon then explained that each evening he would review how he used his time that day. For every moment he wasted, he would mark a dot on a piece of paper. At the end of the day he would look at the paper and ask God's forgiveness for wasting the time.

The point of the story is that time is a precious gift, and how we choose to live each moment makes an eternal difference in our lives. As Moses prayed, "Teach us to count our days rightly, that we may obtain a wise heart" (Psalm 90:13). We obtain such wisdom (chochmah) through the Torah: "And you shall meditate upon (the Torah) day and night" (Josh. 1:8). As disciples, we must study the Scriptures to show ourselves approved before God (2 Tim. 2:15). But study alone is not enough. We must practice the truth and walk it out in our daily lives: "Only take care, and keep your soul diligently... Turn not away from your heart all the days of your life" (Deut. 4:9). "Above all else, keep your heart with diligence, for from it are the outgoings of life" (Prov. 4:23).

הַדְרִיכֵנִי בַאֲמִתֶּךָ וְלַמְּדֵנִי

כִּי־אַתָּה אֱלהֵי יִשְׁעִי

אוֹתְךָ קִוִּיתִי כָּל־הַיּוֹם׃

ha·dri·khei·ni va·a·mit·te·kha ve·la·me·dei·ni

ki at·tah E·lo·hei yish·i

o·te·kha kiv·vi·ti kol ha·yom

"Lead me in your truth and teach me, for you are the God of my salvation;

for you I hope all the day long" (Psalm 25:5)

(Hebrew Study Card)

As followers of Yeshua, we are commanded to "redeem" (ἐξαγοράζω) the time, because the days are evil (Eph. 5:16). The Greek word used here implies exchanging the fleeting moments of the day with the conscious awareness that we will one day stand before the Judgment Seat of Messiah to give account for our lives (Matt. 12:36-37).

May the LORD help us wake up and refuse to exchange the eternal treasure of the Kingdom of God for the fleeting vanities of this world. As the late Jim Eliot succinctly reminded us, "He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose."

Shabbat Shalom to you all.... Stay strong in the Lord Yeshua!

Woman at the Well

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Chayei Sarah (the "life of Sarah"). Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

10.28.10 (Cheshvan 20, 5771) In the same verse that the great patriarch Abraham is described as "old and advanced in years" (זָקֵן בָּא בַּיָּמִים), he is described to have been blessed bakol - "in everthing" (Gen. 24:1). Contrary to the ideals of youth-obsessed culture, the Torah regards aging as a process of construction, of upbuilding, of perfection -- not of decay. The sages say that the elderly "wear the days of their life as a garment," that is, as an accumulated "presence of days" that attends to the soul of the person. Indeed, the Talmud notes that the word zaken ("elder") can be read as zeh kana, "this one has it." Maturity and wisdom are qualities that should be honored in our culture -- not abhorred or disregarded. As the proverb puts it, עֲטֶרֶת תִּפְאֶרֶת שֵׂיבָה / aseret tiferet sevah: "Gray hair is a crown of glory" (Prov. 16:31).

Before he died, however, Abraham wanted to set his affairs in order. His sole land possession in the Promised Land was his burial place (i.e., the Cave of Machpelah (מְעָרַת הַמַּכְפֵּלָה), where Sarah was also buried), but there was a nagging concern that his son Isaac needed a wife to carry on the family line. Indeed, the last recorded words we have of Abraham concern instructions to his servant regarding the mission to find Isaac a wife: "The LORD, the God of heaven (אֱלהֵי הַשָּׁמַיִם), who took me from my father's house and from the land of my kindred, and who spoke to me and swore to me, 'To your offspring I will give this land,' he will send his Angel before you (יִשְׁלַח מַלְאָכוֹ לְפָנֶיךָ) and you shall take a wife for my son from there" (Gen. 24:7). Abraham wanted his son to find a wife among his relatives rather than from among the Canaanites, and he therefore commissioned his servant to arrange a marriage.

Though he is not explicitly named in the account, this "elder servant" is undoubtedly Eliezer of Damascus (Gen. 15:2). Eliezer (אֱלִיעֶזֶר), whose name literally means "my God will help," is regarded as a consummate example of a godly servant. In Christian theology, Eliezer is regarded as a picture of the Holy Spirit (רוּחַ הַקּדֶשׁ) sent on a mission to find a bride for the Sacrificed Seed of Abraham (i.e., the Messiah Yeshua). Eliezer dutifully departs on his mission and waits by the "well of water," interceding on behalf of righteousness... He asks for a sign from heaven: "Let the young woman to whom I shall say, 'Please let down your jar that I may drink,' and who shall say, 'Drink, and I will water your camels' -- let her be the one whom you have appointed" (Gen. 24:13-14). Rebekah's response of kindness and generosity (i.e., חֶסֶד, chesed) to a tired wayfarer demonstrated God's choice. Note that the test concerned the inward character of the woman, not her status or beauty or other worldly factors. And since a single camel needs about 25 gallons of water and requires 10 minutes to drink, watering ten camels would require 250 gallons and at least a couple hours of work running back and forth to the well - no small task for anyone! Rebekah possessed Abraham's qualities of gracious hospitality and diligence...

Rebekah was willing to leave her family - all that she knew - based on an "otherworldly" promise. Her response to the invitation was simply: "I will go"(Gen. 24:58). This courageous willingness was likewise a characteristic of Abraham who was willing to leave his homeland in search of the greater things of God. Like Abraham, Rebekah was ger v'toshav - a "stranger and a sojourner" - who left everything behind in order to become part of God's chosen family...

|

Messiah our Leper

10.27.10 (Cheshvan 19, 5771) The Talmud says "All the world was created for the Messiah" (Sanhedrin 98b). The New Testament had earlier said the same thing: "All things were created by Him (i.e., Yeshua), and for Him" and in Him all things consist (συνεστηκεν, lit. "stick together") (Col. 1:16-17). Indeed, all of creation is being constantly upheld by the word of the Messiah's power (Heb. 1:3). Creation begins and ends with the redemptive love of God as manifested in the Person of Yeshua our LORD... The Messiah is the Center of Creation - its beginning and end. As it is written: אָנכִי אָלֶף וְתָו רִאשׁוֹן וְאַחֲרוֹן ראשׁ וָסוֹף / "I am the 'Aleph' and the 'Tav,' the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End" (Rev. 22:13). "For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever. Amen" (Rom. 11:36). Indeed, Yeshua our Messiah is מֶלֶךְ מַלְכֵי הַמְּלָכִים / Melech Malchei Hamelachim: The "King of kings of kings." He is LORD of all possible worlds -- from the highest celestial glory to the dust of death upon a cross. יְהִי שֵׁם יהוה מְברָךְ / yehi shem Adonai mevorakh: "Let the Name of the LORD be blessed" forever and ever (Psalm 113:2). So while we can agree with the Talmud's general statement that the world was created for the Messiah, we would insist that the Messiah is none other than Yeshua, God's Son, and indeed, the Messiah could be no other...

It is tragic that traditional Judaism does not include Isaiah 53 as part of its yearly Haftarah readings. Perhaps the sages got confused about how to interpret the prophet. This shouldn't surprise us, however, since the prophets were regularly misunderstood and persecuted by various "religious authorities" in Jewish history (see Luke 11:47-51). Still, the sages might have missed the coming of Yeshua because there are two distinct pictures of the Messiah revealed in the visions of the prophets. On the one hand, Messiah is portrayed as a great king, deliverer, and savior of the Jewish people who comes in triumph "in the clouds" (Dan. 7:13), but on the other he is depicted as riding a donkey, lowly and humble, a suffering servant, born in lowliness, despised and rejected of men (Zech. 9:9). These two visions of Messiah eventually led to various oral traditions that there would be two Messiahs: a Messiah ben Joseph (מָשִׁיחַ בֶּן־יוֹסֵף) and a Messiah ben David (מָשִׁיחַ בֶּן־דָוִד). In other words, the sages split the concept of Messiah in two, by regarding one Messiah as a sufferer and the other as a conqueror.

Messiah ben Yosef is identified with the Suffering Servant, of whom the patriarch Joseph prefigured (and of whom Isaiah plainly spoke in his four "Servant Songs"). In some traditions of Judaism, Messiah ben Yosef is recognized as a forerunner and harbinger of the final deliverer, Messiah ben David. Ben Yosef suffers for the sins of Israel and ends up getting killed in the battle against evil for the benefit of ben David (in this way, the two ideas of Messiah were attempted to be "connected" - though not unified). In the Talmud it is written, "When will the Messiah come?" And "By what sign may I recognize him?" Elijah tells the rabbi to go to the gate of the city where he will find the Messiah sitting among the poor lepers (Sanhedrin 98a). "The Messiah -- what is his name?... The sages say, the Leper Scholar, as it is said, 'surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him a leper, smitten of God and afflicted...'" (Sanhedrin 98b). These statements concern the idea of Messiah ben Yosef...

Messiah ben David, on the other hand, is identified as the great military ruler and King of Israel of whom King David prefigures. This greater "son of David" will regather the exiles, set up the (Third) Temple, and deliver Israel from all her enemies. This is the "Shiloh" version of Messiah that the sages of Judaism (such as Maimonides) have long been expecting (for more on the vision of Zion, see "As the Day Draws Near"). Christians believe Yeshua the Messiah in His second coming will completely fulfill this description of Messiah ben David.

The sages apparently were unwilling to unify the various Messianic prophecies in the Tanakh and therefore chose to "divide the visions." Ironically, while they longed for the ideal of Zion to be finally realized, they missed the means by which Zion itself would be established. They did not comprehend that the prophecies concerning the one Messiah would be fulfilled in two distinct ways: Yeshua is both Ben Yosef (the Suffering Servant - at His first coming) and Ben David (the Reigning King - at His second coming). He is also the Anointed Prophet, Priest, and King as foreshadowed by other me'shichim in the Tanakh. Both traditional Jews and Christians are therefore awaiting for the appearance of the Messiah - though His followers will joyfully welcome Yeshua back!

"The Messiah -- what is his name?... The sages say, the Leper Scholar..." (Sanhedrin 98b). But how was it that Yeshua was able to touch the metzora ("leper") and yet remain clean himself (Matt 8:1-4)? Only because He is the LORD, the Healer. Just as Yeshua spoke with greater authority than Moses (Matt. 5:21-48), so He was able to do what Moses (and those under the Levitical system of worship) could not do -- namely, reach down in compassion and take away the uncleanness from our lives.... Yeshua's blood creates the "waters of separation." He is the fulfillment of the "Red Heifer" sacrifice. Only Yeshua enters the "leper colony" of humanity and takes away our tzara'at (sin) by becoming ish machovot (אישׁ מַכְאבוֹת), a leper Himself, the Just for the Unjust, that He might make us acceptable before the LORD. As the prophet Isaiah wrote of Messiah:

"He is despised and rejected of men, a man of pains (אִישׁ מַכְאבוֹת) and acquainted with sickness (וִידוּעַ חלִי), and we hid as it were our faces from him. He was despised and we esteemed him not. Surely he has carried our sicknesses (חֳלָיֵנוּ) and borne our pains (מַכְאבֵינוּ), yet we esteemed him as plagued (נָגַע), smitten of God (מֻכֵּה אֱלהִים) and oppressed. But he was pierced (מְחלָל) for our transgressions (פְּשָׁעֵנוּ), he was crushed for our iniquities (עֲוֹנתֵינוּ): the discipline for our peace was upon him (מוּסַר שְׁלוֹמֵנוּ עָלָיו); and in his blows we are healed. All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way, but the LORD has attacked in him (הִפְגִּיעַ בּוֹ) the iniquity of us all" (Isa. 53:3-6)

"The LORD has "attacked in him (הִפְגִּיעַ בּוֹ) the iniquity of us all..." (Isa. 53:6). Through the substitutionary sacrifice of the righteous Suffering Servant, Yeshua, we are both forgiven and made free from the power of sin and death. Because of Him we are no longer "lepers" or outcasts from the community of God but are made clean through His loving touch.

Addendum: Jewish tradition states that teshuvah (repentance) was created at twilight just before the first Sabbath (Berachot 54a), that is, concurrent with the creation of Adam and Eve (see the "Gospel in the Garden"). Repentance is a response to sin, which is understood as a form of spiritual sickness that leads to death: "Bless the LORD, O my soul, and forget not all his benefits, who forgives all your iniquity, who heals all your diseases, who redeems your life from destruction, who crowns you with chesed and mercy" (Psalm 103:2-4). God's forgiveness is linked with healing and redemption from death and destruction (שַׁחַת). "By his stripes you were healed" (Isa. 53:5). It is written: "God creates the cure before the plague." Just as God created mankind only after He created the pathway of repentance (i.e., Yeshua is described as the "Lamb slain from the foundation of the world": 1 Pet. 1:20, Eph. 1:4, Rev. 13:8, 17:8), so the purification from sin and death was likewise foreseen and provided for by means of the Cross of the Messiah. God chose to save the "leper colony" of humanity by bearing the sickness Himself: "For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses (ἀσθένεια), but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin" (Heb. 4:15).

|

The Promise of Shiloh

[ The following entry is out of sequence with the weekly Torah readings, though it continues the theme of the "Promised Seed" (i.e., the Messiah) as revealed in Book of Genesis: 'of the Woman, of Shem, of Abraham, of Isaac, of Jacob, of Judah...' ]

10.27.10 (Cheshvan 19, 5771) In the "Gospel in the Garden" we considered the very first prophecy given in the Torah, namely, God's promise that through the "seed of the woman" would come one who would slay the serpent and crush the kingdom of Satan (Gen. 3:15). "... He (i.e., the Savior/Messiah) will crush your head (ראשׁ), and you (i.e., the serpent/Satan) will crush his heel (עָקֵב)." Eve initially had hoped that her firstborn son was the promised child, but Cain later proved to be a murderer. The martyrdom of her righteous son Abel necessitated that the promised seed would descend through another child, and therefore the Torah describes the birth of Seth (שֵׁת, lit. "appointed"), the third son of Adam and Eve. The Scriptures state that it was the descendants of Seth who "began to call upon the Name of the LORD" (לִקְרא בְּשֵׁם יהוה), indicating that they had faith in God (אֱלהִים) as the Compassionate Covenant Keeper (יהוה) who would deliver humanity from the curse by means of victory (נצח) the promised Seed.

Apart from the "godly line of Seth," however, the subsequent lineage of humanity was marked by anarchy and bloodlust, so that the Torah describes the human condition as "every intention of the thoughts of man's heart was only evil continually" (Gen. 6:5). After nine generations from Adam, the LORD "had enough" and was ready to wipe humanity from the face of the earth. The Torah then traces the genealogy (toldot) of Seth through ten generations (from Adam), until his descendant Noach (נחַ) is described as the only tzaddik (righteous man) remaining in the earth (Gen. 6:6-9). The Great Flood came as a worldwide judgment upon fallen humanity that had rejected the way of truth and righteousness (Gen. 6:5-7). After the great cataclysm, we learn that Noah's son Shem (שֵׁם) was chosen to be the one through which the "line of the Messiah" would come. When Noach said, "Blessed be the LORD, the God of Shem" (בָּרוּךְ יהוה אֱלהֵי שֵׁם), he prophesied that the coming redemption would come through the line of Shem (not through Canaan or Japheth), and therefore Shem was chosen to be humanity's high priest (for more on this, see the "Seed of Abraham").

From the line of Shem would descend Abram (אַבְרָם), the tenth generation from Noah, and therefore the twentieth from Adam (for the genealogy, see parashat Noach). Abram, of course, is the original patriarch of the Jewish people who was tested to offer up his "only begotten son" (his own "promised seed") as a sacrifice upon Mount Moriah, the location of the future Temple. In Jewish tradition, this supreme test is called the Akedah (עֲקֵדָה, "binding"), which clearly prefigured the Father's sacrifice of the Son of God for the sins of humanity (more here). Indeed, after the offering of Isaac, God explicitly promised Abraham that "in your seed (זֶרַע) shall all the nations of the earth be blessed, because you have obeyed my voice" (Gen. 22:18).

Throughout the lives of the original patriarchs, the promise of the coming Seed was repeated and reaffirmed. Abraham received the promise six times (Gen. 12:1-3, 13:14-18; 15:4-5; 17:1-8; 18:18, 22:18), Isaac received it twice (Gen. 26:3-4, 23-24), as did Jacob (Gen. 28:10-14; 35:9-12). The patriarchal promise of the coming seed was therefore made (or reaffirmed) no less than ten times in the Torah (corresponding to the ten utterances that created the universe). The Redeemer would therefore come from the "God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob" (אֱלהֵי אַבְרָהָם אֱלהֵי יִצְחָק וֵאלהֵי יַעֲקב), just as Yeshua Himself later affirmed, "salvation is from the Jews" (John 4:22).

The next development of the promise of coming Redeemer occured on the deathbed of the patriarch Jacob. When the time came for Jacob (i.e., Israel) to die, he called all his sons together to bless them (Gen. 49:1-28). According to midrash, Jacob wanted to tell his sons about the "End of Days" (אַחֲרִית הַיָּמִים) when the Messiah would come, but was prevented by the Holy Spirit. According to Rashi, God prevented Jacob because He does not want anyone to know the "day or the hour" when the great King of Israel would appear. Jacob did, however, foretell that from the tribe of Judah (יְהוּדָה) would come the Messiah: "The scepter (שֵׁבֶט) will not depart from Judah, nor the ruler's staff from between his feet, until Shiloh (שִׁילוֹ) comes, and to him shall be the obedience (יקְהָה) of the people" (Gen. 49:10). Interestingly, the name "Judah" (יְהוּדָה) is spelled using all the letters of the Name YHVH (יהוה), with the addition of the letter Dalet (ד). Just as the tribe of Judah later was directly stationed in the front of the Mishkan (Tabernacle) in the camp formation in the wilderness, so the Holy Temple (i.e., Moriah) would later become part of Judah's territory in the promised land. Likewise, Yeshua Himself - a descendant of King David - was crucified and resurrected in the land of Judah. Truly the promised "Seed of Judah" represents the "doorway of the LORD" and is rightly named "the One whom his brethren would praise."

The meaning of the word "Shiloh" has been debated among scholars and commentators. According to early sages and Talmudic authorities, the "ruler's staff from between his (Judah's) feet" refers to the Messiah (Targum Onkelos, Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, and Targum Yerusahlmi), and the word "Shiloh" comes from she-lo, meaning "that is his." In other words, kingly authority would be vested in the tribe of Judah until the Messiah appears, at which time he would reign as the supreme leader of the people. The Talmud likewise supports the interpretation that Shiloh was a reference to the Messiah: "Rabbi Yochanan taught that all the world was created for the Messiah. What is His name? The School of Sheeloh taught: His name is Shiloh as it is written, 'Until Shiloh come and unto Him shall the gathering of the peoples be'" (Sanhedrin 98b). In later rabbinical tradition, "Shiloh" was construed to mean "final tranquility" or the worldwide peace brought through the rule of the Messiah, when all the nations of the earth would submit to him. Understood in this light, "Shiloh" would refer to the establishment of the kingdom of God upon the earth (i.e., the Zionist vision). Others have said that since the Masora renders shiloh using a mappiq in the final Hey (i.e., הּ), it should be regarded prepositionally to mean "toward Shiloh," the very first capital of Israel in the Promised Land (this interpretation suffers from the fact that Shiloh was in Ephraim, not in Judah, however). Still others have said that Shiloh should be regarded as a proper name functioning as the subject of the verb "shall come." In this interpretation (common in most Christian translations of the Bible), Shiloh (said to derive from the verb shala, "to rest"), would then be the first proper name given to the Messiah in the Scriptures. Despite some of the uncertainty regarding the exact meaning of the name "Shiloh," the various commentators - both Jewish and Christian - agree that Jacob's prophecy concerned the regal authority of the tribe of Judah until the Messiah would appear. This is the basis for the "Son of David" hope of Biblical Judaism.

As an aside, Jacob's prophecy that "the scepter will not depart from Judah... until Shiloh comes" includes all the letters of the Hebrew alphabet except for the letter Zayin, which is the Hebrew word for weapon, suggesting that when the Messiah comes, it will not be by means of arms or weapons, but rather by the ruach ha-kodesh. In other words, the Zealots misunderstood the mission of the Messiah, thinking that the Messiah would rule and reign by means of carnal force and worldly power. Therefore we see Yeshua as the Suffering Servant, Mashiach ben Yosef, coming to the Temple riding on a lowly donkey, full of humility and kindness (Matt. 21:1-5).

The time of Shiloh's coming is somewhat problematic, however, at least from a traditionally Jewish perspective. After all, the kingdom of Judah was later taken into captivity in 587 BC when Tzediakiah was captured and taken prisoner in Babylon, though the land was still technically governed by Zerubbabel and later by the Great Assembly (Sanhedrin). During the intertestamental period, the territory was still called Judea (after the name of the tribe). However, after Rome conquered the land and made it into a Roman province (AD 6-7), the political power of Judah was officially over. Indeed, after the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70 and the subsequent Jewish-Roman wars, the Jewish people began their long and tragic exile from the land - and the hope of the kingdom appeared lost...

Historically speaking, if we understand the "regency of Judah" to be invested in the Great Sanhedrin (after the last independent King of Judah [Tzedekiah] was deposed), the scepter (shevet) would have departed from Judah in AD 6-7 after the Romans installed a procurator as the authority in Judea (thus replacing the authority of Sanhedrin based in Judah). However, the prophecy of Jacob did not fail, because the Messiah had indeed come and was in their midst as Yeshua mi-netzeret (Jesus of Nazareth) at that exact time. In other words -- Yeshua is indeed Shiloh - the King of the Jews - though at present He is not physically reigning on David's throne (this will occur at His Second Coming when he returns to Jerusalem at the end of olam ha-zeh (this present age) to establish the Kingdom of God upon the earth).

Like most prophecies in Scripture, the prophecy of Shiloh has a "dual aspect" or "double fulfillment." Shiloh, or the "King of the Jews" (a synonym for the Messiah, called "Christ" by Gentile Christendom) had indeed come "before the scepter departed from Judah," but he went unrecognized since he came to fulfill the role of the Suffering Servant (Mashiach ben Yosef). The second part of the prophecy, "and to him shall be the obedience of the people," is yet to be fulfilled. It will become a visible reality only after his Second Coming, at the end of olam ha-zeh (this present age), when Yeshua comes to judge the nations (the "sheep and the goats") and establish the Kingdom of God from David's throne in Jerusalem.

The Promised Seed was to be born of a woman (Gen. 3:15), to dwell in the "tents of Shem" (Gen. 9:26) and descend from the line of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Gen. 12-28). Furthermore, as Jacob's prophecy makes clear, the tribe of Judah would be known as Gur Aryeh (גּוּר אַרְיֵה), a "Young Lion," who would be praised, made victorious, and rule over the other tribes of Israel (Gen. 49:8-9). Indeed, from the royal tribe of Judah would come the Messiah, the anointed King of Israel, whose authority would ultimately expand into a worldwide dominion (Gen. 49:10). As later prophecies clearly foretell, the great "Young Lion of the Tribe of Judah" is none other than Yeshua, the Son of God, unto whom every knee shall bow, and every tongue confess, that He is indeed the Lord of Lords and the King of Kings... The day of His coming draws near...

|

"All the world was created

for the Messiah"

Addendum:

Are Christians "Spiritual Jews"?

The word "Jew" comes from Judah (יְהוּדָה), from the root (יָדָה) which means to "thank." From Judah was derived the later term "Jew" (which first appears after the destruction of the First Temple, 2 Kings 25:25, and was later used in the Aramaic books of Ezra/Nehemiah). Leah used a play on words regarding her birth of her fourth son when she said she would "thank the LORD" (אוֹדֶה אֶת־יהוה), and therefore named her son "Judah" (Gen. 29:35). I think Paul alluded to this in Rom. 2:28-29 by saying that an "inward" Jew is "one who praises (or thanks) God," and therefore it may be said that all those who thank the LORD in the truth are "spiritual Jews." If you are "blood-related" to God by the Messiah through faith, you are "grafted in" to the covenants, promises, and blessings originally given to ethnic Israel, and are therefore a member of "God's household" in full standing (see Eph. 2:12-22).

"So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are fellow citizens with the saints (tzaddikim) and members of the household of God (i.e., b'nei Elohim)." [Eph. 2:19] Non-Jews who accept the salvation offered by Yeshua are fellow heirs, members of the same body, and partakers of the promise in Messiah through the gospel (Eph. 3:6). As was repeatedly promised in the Torah, the blessing of Abraham is imparted to all the families of the earth because of Yeshua (Gal. 3:14).

|

Imminence and Redemption

[ It's a stormy day here in Minnesota, with strong gales and glowering skies, almost as if nature itself is foretelling the greater storm that soon comes to test all the earth. ]

10.26.10 (Cheshvan 18, 5771) According to Orthodox Jewish halakhah (law), belief in the coming of Mashiach (the Messiah) is required to be rightly regarded as a Jew. The twelfth principle of Maimonides states, "I believe with complete faith in the coming of the Messiah, and though he may delay, nevertheless I am waiting for his coming every day." Accordingly, anyone who rejects or doubts the imminent return of the Messiah is considered "apikoros," (i.e., heretical). Even those who (abstractly) believe that the Messiah will come "some day" are regarded as unbelieving, since this attitude negates the unconditional expectation of his imminent arrival. Indeed, the obligation to expect the coming day of redemption applies to every minute of every day. As it is written in the Scriptures:

הַדְרִיכֵנִי בַאֲמִתֶּךָ וְלַמְּדֵנִי

כִּי־אַתָּה אֱלהֵי יִשְׁעִי

אוֹתְךָ קִוִּיתִי כָּל־הַיּוֹם׃

ha·dri·khei·ni va·a·mit·te·kha ve·la·me·dei·ni

ki at·tah E·lo·hei yish·i

o·te·kha kiv·vi·ti kol ha·yom

"Lead me in your truth and teach me, for you are the God of my salvation;

for you I hope all the day long" (Psalm 25:5)

(Hebrew Study Card)

The sages state that the fervent expectation of the Messiah's coming actually hastens geulah (redemption). Just as the prayers and sighs of the Jews in Egypt caused God to commission Moses, so the prayers of the tzaddikim move the LORD Messiah to action (Rev. 8:4). On the other hand, if we do not expect imminent redemption, our troubles and suffering will increase and increase (the "birthpangs of the Messiah") until they culminate in the "Time of Jacob's Trouble" - עֵת־צָרָה הִיא לְיַעֲקב (Jer. 30:7). Waiting with expectancy is a matter of personal as well as corporate responsibility: "When a man is led in for judgment in the world to come, he will be asked, 'Did you await the salvation?'" (Shabbat 31a). On the other hand, "date setting" or claiming that the Messiah can come only at certain times or seasons "mars" the expectation of redemption. The time of the redemption is concealed, and "no man knows the day or hour" (Matt. 24:36). Forecasting the exact time or date of the Messiah's return may even cause a lax attitude and unreadiness for his glorious appearance (Luke 12:45-46).

But why wouldn't the LORD want to tell his children the hour of the promised Messiah's appearance? According to tradition, if people knew how long they would have to wait, they might despair of life altogether, or, if they knew the exact time, they might "repent" just for that reason, and not because it came from the heart...

Yeshua said, "Behold, I come quickly (ταχύ)..." (Rev. 3:11; 22:12). It is a mitzvah to wait patiently for the return of Yeshua our Messiah. Our "inward groaning" for the fulfilment of our redemption is the very hope by which we are saved (Rom. 8:23-24). The imminency of His return should fill our hearts with joyful excitement. Just as the Jews awaited liberation from bondage in Egypt "with loins girded, shoes on feet, and staff in hand" (Exod. 12:11), so too must we be ready to receive our Redemption at any moment. "Thus says the LORD: "Keep your voice from weeping, and your eyes from tears, for there is a reward for your work, declares the LORD, and they shall come back from the land of the enemy" (Jer. 31:16).

בִּלַּע הַמָּוֶת לָנֶצַח

וּמָחָה אֲדנָי יהוה דִּמְעָה מֵעַל כָּל־פָּנִים

bil·la ha·ma·vet la·ne·tzach,

u'ma·chah Adonai Elohim dim·ah mei·al kol pa·nim

"He will destroy death forever.

The Lord GOD will wipe the tears away from all faces" (Isa. 25:8)

(Hebrew Study Card)

There is an old story of the Maggid of Brisk who each year would bring proof from the Torah that the Messiah would come that year. Once a certain Torah student asked him, "Rabbi, every year you bring proof from the Torah that the Messiah must come that year, and yet he does not come. Why bother doing this every year, if you see that Heaven ignores you?" The Magid replied, "The law states that if a son sees his father doing something improper, he is not permitted to humiliate him but must say to him, 'Father, the Torah states thus and so.' Therefore we must tell God, who is our Father, that by keeping us in long exile, he is, in a sense, causing injustice to us, and we must point out, "thus and so it is written in the Torah," in hope that this year he might redeem us." This same principle, of course, applies to those of us who are living in exile and who eagerly await the second coming of the Messiah Yeshua. We should continue asking God to send Him speedily, and in our day, chaverim...

Regarding the Messiah's Second Coming, we therefore find ourselves in the same position of expectation as Israel's sons who heard the original prophecy from the patriarch Jacob: "the scepter will not depart from Judah, nor the ruler's staff from between his feet, until 'Shiloh' (שִׁילוֹ) comes..." (Gen. 49:10). Though Jesus told us about the "signs" of the time (and the "fig tree has brought forth its leaves," see Matt. 24:32-33), we do not know the exact "day or the hour" and therefore must be ready for his return at any time (Matt. 24:36-25:13). Nonetheless, the Spirit that gives life to hope within us cries out: "Come quickly, Yeshua!"

|

Strangers and Settlers

[ The following is related to this week's Torah reading, Chayei Sarah (the "life of Sarah"). Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

10.25.10 (Cheshvan 17, 5771) When Abraham approached the Hittites, wishing to acquire a place to bury his wife Sarah, he said: "I am a sojourner and settler (גֵּר־וְתוֹשָׁב) among you; sell me a burial site..." (Gen. 23:4). King David likewise confessed: "For we are strangers with You, mere transients like our fathers (כִּי־גֵרִים אֲנַחְנוּ לְפָנֶיךָ וְתוֹשָׁבִים כְּכָל־אֲבתֵינוּ); our days on earth are like a shadow, without hope" (1 Chron. 29:15). Life in olam hazeh (this world) is nothing but a "burial site," a graveyard, a shadowy place of passing that leads to olam haba, the world to come, and to God's glorious kingdom. We cannot find lasting hope in this world and its values; all that must be buried and surrendered to God.

Being gerim v'toshavim (גֵרִים וְתוֹשָׁבִים), "strangers and sojourners," is inherently paradoxical, however, since a ger (גֵּר) is one who is "just passing through," like a visitor or refugee, whereas a toshav (תּוֹשָׁב) is one who is a resident, like a settler or citizen. Living by emunah (אֱמוּנָה, faith) therefore invariably leads to collision with worldly culture and its values. Faith affirms that underlying the surface appearance of life is a deeper reality that is ultimately real and abiding. It "sees what is invisible" (2 Cor. 4:18) and understands (i.e., accepts) that the "present form of this world is passing away" (1 Cor. 7:31). The life of faith therefore calls us to live as toshavim - sojourners - who are put at an infinite "distance" from the world of appearances. We ache with a divine "homesickness." We lament over the state of this world and its delusions. We gnaw with hunger for love and truth to prevail in the world. And yet this loneliness, this dissonance, this place of suffering "outside the camp" is not without an overarching comfort:

This slight momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison, as we look not to the things that are seen but to the things that are unseen. For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal. For we know that if the tent (σκηνος), which is our earthly home, is destroyed, we have a building from God, a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens. For in this tent we groan, longing to put on our heavenly dwelling.

(2 Cor. 4:17-5:2)

If we are given grace to answer the call of Yeshua to "take up our cross," we presently become ger v'toshav. As gerim we confess that we are strangers in this present world, but as toshavim we believe that our labors are not in vain, and that our true citizenship is in heaven. Like father Abraham, we live in a foreign land as "strangers and sojourners," looking forward to the City of God (Heb. 11:9-10).

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יהוה אֱלהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אָבִינוּ מֵעוֹלָם וְעַד־עוֹלָם

ba·rukh at·tah Adonai E·lo·hei Yis·ra·el A·vi·nu me·o·lam ve·ad o·lam

Blessed are You, LORD, God of Israel our father,

from eternity to eternity (1 Chron. 29:10).

(Blessing Card)

May His Kingdom come speedily, and in our day, and may the LORD help us live today -- in this world -- as ambassadors and emissaries of the world to come. Amen.

Note: Of course I don't mean to suggest that we are to be so "otherworldly" that we are no earthly good. No, but many of us are so "this-worldly" that we are of no heavenly good! The direction must be first toward heaven, and then back to earth ("seek ye first the kingdom..."). We surrender to God and then receive back our lives to reengage the world. "Unless a seed falls to the ground and dies, it abides alone; but if it dies, it brings forth fruit" (John 12:24). Life in this world must be "mediated" by the presence of God through our faith in Him. Only then are we able to truly love and care for the world as God's emissaries.

Addendum:

The Warning of Reformed Judaism

The German "Reform movement" (Haskalah) began in the mid-nineteenth century. The goal of the movement was presumably to "enlighten" Jews and to help them assimilate into German culture. The structure of synagogue service was altered to resemble German Lutheranism (with organ music, men and women sitting together, etc.), and German - not Hebrew - became the language used in the liturgy. In addition, secular study and a "higher critical" understanding of the Scriptures was encouraged, and Jews were instructed to stop living isolated lives within the "ghettos," but rather to integrate as "full members of German society." This approach later culminated in the "motto" of the Reform movement: "Berlin is Jerusalem" (see the "Christian" corollary here). In other words, Berlin was just as good as Jerusalem, and the ideals of the Promised Land, the Torah, and the ultimate destiny of the Jewish people became allegorized (and therefore of merely symbolic significance).

Tragically, it took the horrors of the Second World War and the rise of the hateful Nazi party to disabuse the German Jewish community that they were not regarded as true "citizens" of Germany. The reformed Jews of Germany had focused so much on being "residents" of land that they had forgotten that they were first of all "strangers and exiles on the earth" (Heb. 11:13).

|

Parashat Chayei Sarah - חיי שרה

[ This week's Torah reading is called Chayei Sarah (the "life of Sarah") which begins (paradoxically enough) with the account of Sarah's death (Gen. 23:1-2). If you haven't already done so, please first read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

10.24.10 (Cheshvan 24, 5771) Recall that Sarah gave birth to Isaac when she was 90 years old and later died at age 127, when Isaac was 37 years old. The Torah does not explicitly state the cause of her death, though according to Jewish tradition Sarah died from shock after learning about what happened to her son at the hand of her husband (i.e., the near sacrifice of Isaac at Moriah). It was just too much for her heart to bear. How could she comprehend Abraham's actions? Was he insane? And what about Isaac? How could Sarah bear the terror her son must have endured? And what about the cherished dream of the family to be God's chosen people on the earth? Because of this great trauma, her soul departed from her....

The midrash elaborates by explaining that after Abraham's early departure (for Moriah) Sarah grew more and more worried about the welfare of her son. By the third day - the day of the Akedah itself - she decided to go look for him. When Sarah reached Hebron, however, the evil one disguised himself as her (disfigured) son. When she saw him, she asked: "My son, what has your father done to you?" He answered, "My father took me and made bound me on the altar. He then took the knife to slaughter me. If the Holy One had not called out, 'Do not cast your hand on this boy,' I would have been slaughtered." When she heard how her son had been bound on the altar, Sarah was so overcome with fright that her soul had departed from her" (Midrash Tanchuma).

Therefore when the Torah says, "And Abraham came to mourn for Sarah and to cry for her" (Gen. 23:2), the sages say that he was returning directly from Mount Moriah, the place of the sacrifice of Isaac. (This also explains why Isaac was not present at his mother's funeral since he had fled from Abraham and sought refuge with Shem in Salem after the terrifying ordeal). In the Torah text the phrase "and to cry for her" (וְלִבְכּתָה) is written with a diminutive letter Kaf, which has led some of the commentators to explain that Abraham's mourning for his wife was restrained. How are we to understand this? The sages state that the death of Sarah was yet another severe test for Abraham. Would he now regret his faithful obedience to the LORD because of the loss of his wife? The Akedah settled the question that Abraham loved God more than even his beloved son, but the death of Sarah was another matter.... Since Abraham believed that God would raise his son from the dead, perhaps he likewise believed that God would raise his wife from the dead (Heb. 11:17-19). At any rate, to indicate that Abraham loved God unconditionally, the letter Kaf was written smaller, suggesting that his mourning was tempered with continued trust in God's will and plans...

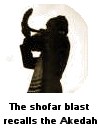

It is a provocative thought that Sarah - not Isaac - was the real victim of the Akedah. She, not Isaac, is the one who dies, after all. Jewish tradition has associated the cries of Sarah with the blasts of the shofar during Rosh Hashanah. The broken notes of the shofar are thought to recall her crying for her son...

The sages further wonder why Sarah lived only 127 years while Abraham lived to be 175, that is, 48 years more? They answer that Sarah's years amounted to the number of years Abraham lived as ha-Ivri (הָעִבְרִי), "the Hebrew," a term that identifies his relationship to the one true God (see "Abraham the Hebrew"). Since Abraham was 48 years old when he came to believe, and a convert is regarded as a newborn, then Abraham lived (as a Hebrew) exactly 127 years, precisely as long as did Sarah (who was regarded a prophetess from birth). For more about this, please see the article "The Greatness of Sarah."

|

The Akedah of Isaac:

Love and Sacrifice

[ The following entry (related to parashat Vayera) concerns the crucial topic of the "Akedah," or the offering of Isaac, and how this amazing drama - told in just nineteen verses of Torah (Gen. 22:1-19) - clearly foretold the sacrifice of Yeshua our Redeemer. Please note that I wrote the following in haste so you could read it in time for this coming Shabbat. It is presently a "work in progress," chaverim... ]

10.21.10 (Cheshvan 13, 5771) The very first occurrence of the word "love" in the Scriptures refers to Abraham's passion for his son Isaac (i.e., the word ahavah: אַהֲבָה, in Gen. 22:2). Isaac was the long-awaited heir, Abraham's "miracle boy," his only child of his beloved wife Sarah. God Himself named Isaac before his birth in anticipation of the "laughter" and great hope he would bring to Abraham and Sarah. Indeed, it was this very hope in God's promise that moved God to rename Abram to Abraham, and Sarai to Sarah... In short, Isaac represented all the dreams and aspirations of Abraham's heart. In light of this, imagine the agony and turmoil Abraham experienced when God asked him to sacrifice his beloved and irreplaceable son. Would Abraham be willing to obey - even if that meant destroying his dream for Isaac - and indeed all his hopes? More radically, would Abraham be able to trust God - even if that meant surrendering his understanding and rationality?

In Jewish tradition, the drama of the mind-blowing sacrifice of Abraham's beloved son is called the Akedah (עֲקֵדָה, "binding"), which is universally regarded as the supreme test of Abraham's obedience and faith. The Akedah is so important that it is read each morning as a prelude to the Shacharit (morning) service. It is also read during Rosh Hashanah, since tradition says that Abraham sacrificed his son during this time. The blast of the shofar is intended to remind us of God's gracious atonement provided through the substitutionary sacrifice of the lamb (as well as to "drown out" the voice of the accuser). In this way, the Akedah represents the truth of the Gospel, and how God's attribute of justice was "overcome" by His attribute of compassion (Psalm 85:10).

"After these things..."

The story of the offering of Isaac, Abraham's "promised seed," begins with the statement, "After these things God tested Abraham..." (Gen. 22:1). Notice that the phrase, "after these things" (וַיְהִי אַחַר הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלֶּה) grammatically connects the preceding narrative of Abraham's expulsion of his son Ishmael at God's command (Gen. 21:12-14) and the covenant he made with Abimelech at Beersheba (Gen. 21:-22-32). The verses that immediately precede the account of the Akedah, however, read: "Abraham planted a tamarisk tree in Beersheba and called there on the name of the LORD, the Everlasting God. And Abraham sojourned many days in the land of the Philistines" (Gen. 21:33-34). Since Abraham was in the godly line of Seth and Shem, he undoubtedly believed in the promise of the coming "seed of the woman" who would "reverse the curse" originally given to humanity (Gen. 3:15). Did the "tamarisk tree" recall the original Tree of Life that the LORD promised would be restored by the promised seed? Did Abraham believe that his son Isaac was the Redeemer to come?

"God tested Abraham..."

"After these things God tested Abraham..." Pirke Avot 5:3 says, "With ten tests our father Abraham was tested and he withstood them all -- in order to make known how great was our father Abraham's love for God." The sages list these tests as:

- Rejecting the religion (idolatry) of his father Terach (Josh. 24:2).

- Leaving the country of his birth for an unknown land (Gen. 12:1).

- Being tested with famine upon entry to the Promised Land (Gen. 12:10).

- Dealing with Sarah's abductions (Gen. 12:14-15; 20:2).

- Interceding for Lot and fighting against the four kings (Gen. 14:12-16).

- Experiencing the dreadful vision of future captivity (Gen. 15:1-21).

- Undergoing painful circumcision at age 99 (Gen. 17:10).

- Enduring the infertility of Sarah, despite the promise of an heir (Gen. 11:30; 15:3).

- Evicting his wife Hagar and his firstborn son Ishmael (Gen. 21:9-14).

- Sacrificing his beloved son Isaac as a burnt offering (Gen. 22:1-19). The sages universally agree that the sacrifice of Isaac was the most difficult test (nissayon) Abraham faced (see below for more).

"Here I am..."

So the story of the Akedah begins: "After these things God tested Abraham and said to him, "Abraham!" And he said, "Here am I" (Gen. 22:1). After some 30 years of silence, living as a sojourner among the Philistines, God finally called to faithful Abraham, who simply answered, "Here I am" (i.e., hineini: הִנֵּנִי). What is remarkable about this "hineini" is that it is Abraham's only recorded response to God's forthcoming request: "Take your son, your only son, whom you love, even Isaac, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you" (Gen. 21:2).

The midrash adds some imaginary dialog between God and Abraham in order to explain the rhetoric used in this verse of the Torah: "Take your son, your only son, whom you love, even Isaac":

God (אֱלהִים) said: "Take your son (בֵּן)." Abraham answered, "Which one? I have two sons." So God said, "Your only (יָחִיד) son." Abraham answered, "But each one of the two is the only one of his mother." So God said, "Whom you love (אֲשֶׁר־אָהַבְתָּ)." Abraham answered, "I love both." So God finally named the son directly: "Even Isaac (אֶת־יִצְחָק)." (Midrash Rabbah, Bereshit)

Despite the speculation provided by midrash, the written Torah records that when God called out to Abraham to sacrifice his beloved son, Abraham replied with only one word: hineini, "Here I am," and began immediately preparing for the sacrifice. And as we will see in the subsequent narrative, three days would pass from the time God asked Abraham until they arrived at Moriah, and the Torah only records that Abraham said this one word: hineini. Both God and Abraham were silent during this awful test of faith...

"Go to the land of Moriah..."

"Please take (קַח־נָא) your son, your only son, whom you love, even Isaac, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you" (Gen. 21:2). Notice that the phrase "go to the land of Moriah" uses the same verb that God used to call Abraham to leave for the Promised Land (i.e., lekh-lekha: לֶךְ־לְךָ in Gen. 12:1). So the progression is first "go for yourself" from the land of your origin (i.e., the realm of the flesh, of natural human life), and then "go for yourself" to the place of atonement and substitutionary sacrifice (i.e., the realm of the spirit, of eternal life)....

The land of Moriah (אֶרֶץ הַמּרִיָּה) was not unknown to Abraham, since it was understood from the time of Adam and Eve to have been the place where God created the universe. The dust of Moriah is said to have been used to create Adam, and Mount Moriah was said to have been the place that Adam first offered sacrifice, as did his sons Cain and Abel. After the Great Flood, Noah commission his firstborn son Shem to be the family high priest (Malki-Tzedek). Shem later established a school at Moriah that became the central place of Torah study for the post-flood generation. According to tradition, Shem called the place Shalayim (i.e., Shelem, "perfect"), since the bedrock at Moriah was called Even ha-Shetiyah (אבן השתייה), "the Foundation Stone," referring to the creation of the earth on the First Day (Isa. 28:16). Later, Abraham called the place Adonai Yireh ("God will provide"), and subsequently Moriah was renamed by combining these two to form Jerusalem. At any rate, the mountain which God would show Abraham was none other than Zion, the Mountain of the LORD, and the site of the future Temple (as well as the crucifixion of Yeshua).

It should be noted here that some commentators claim that Abraham actually misunderstood God's commandment to offer up his son. When God said, "Take your son... and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there" (Gen. 22:2), God did not intend for Abraham to kill Isaac, but only that he should "dedicate" him upon the altar at Moriah. The Hebrew verb alah (עלה) can mean "to ascend" or "to climb" in addition to turning something into smoke (i.e., via burnt offering). Understood in this way, the command could be rendered, "Take your son... and go to the land of Moriah and cause him to ascend [הַעֲלֵהוּ] there for an ascent [לְעלָה] upon one of the mountains which I will tell you." In other words, the Hebrew verb translated "offer him up" [הַעֲלֵהוּ] should have been understood as "cause him to ascend," perhaps in a way similar to Jacob's vision of the ladder that ascended toward heaven. Rashi notes that when God said, "Which [i.e., the sacrifice of humans] I commanded not, nor did it come into My mind" (Jer. 7:31) refers to Isaac, whom God never intended to slaughter, but only to be tested (Ta'anit 4a).

Abraham, however, understood God's instruction to mean that Isaac was to be offered as a human sacrifice (i.e., a whole burnt offering (עוֹלָה)), a cult practice not uncommon among the pagan cultures immersed in Molech idolatry. Some have speculated that the test given to Abraham centered primarily on renouncing such pagan conceptions of God. The temptation to elevate blind obedience to an arbitrary deity (אֱלהִים) above the dictates of compassion and conscience had to be overcome. Abraham's temptation, so to speak, was whether to listen to the voice of God (אֱלהִים) or to heed the voice of the LORD (מַלְאַךְ יְהוָה).

Why didn't Abraham argue with God (אֱלהִים) by remembering Him as the LORD (יְהוָה), the Compassionate Source of life? Earlier he had argued with God regarding the destruction of Sodom. So why didn't he argue to save his own son? Might this have been Abraham's test, namely, that God wanted Abraham to argue and to challenge the command to perform child sacrifice? Or why didn't he ask, "Why do you taunt me by giving me a son in my old age only to have him taken away?" Why didn't Abraham protest that his descendants could never inherit the Promised Land if his heir were killed? Indeed, how could Abraham have been in his right mind during this test? As Soren Kierkegaard reminds us in his book Fear and Trembling, this is yirat Elohim - the fear of God - taken to point of sheer madness.

"He arose early..."

"So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac. And he cut the wood for the burnt offering and arose and went to the place of which God had told him" (Gen. 22:3).

Instead of arguing with God about the rightness of the request, Abraham immediately began preparing for the sacrifice. He did not question God's instructions, nor, as we know from New Testament Scripture, did he doubt that God would be able to fulfill His promise that Isaac would be the heir of a multitude of people. Abraham "saddled his donkey," indicating that he took personal responsibility for his mission. The midrash states that the two young men were Ishmael and Eliezer, respectively. Abraham cut the wood for the burnt offering ahead of time, though this is left unexplained in the text of the Torah (a midrash states that it was to ensure that the wood was "kosher," that is, worm-free). Another possibility is that the wood was considered sacred to Abraham, perhaps cut from the terebinth tree he had earlier planted at Beersheba.

The Miracle of the Test

There are countless commentaries written about the Akedah, with various theories about what it all means or why the test was administered. Some of the sages link "after these things" (Gen. 22:1) with the treaty Abraham had earlier made with Abimelech (Gen. 21:27). God was angry at Abraham for making this covenant since He had promised to give all the land of Canaan to his descendants. Now Abraham's children would be unable to conquer the land until Abimelech's grandson would die. In effect, Abraham's decision to covenant with the Philistines resulted in the exile to Egypt, and the test of the Akedah was meant to refine Abraham's faith and obedience...

A midrash states that after Isaac had become a wealthy man, his older brother Ishmael visited him and taunted him regarding the virtue of circumcision. "I was thirteen years old when God commanded my father to circumcise us. I willingly submitted to this painful operation in obedience to my father and to God. But you, on the other hand, were a mere baby, before you had the intelligence to protest." Isaac replied, "You praise yourself because of one organ of your body, but I swear that if God commanded my father to sacrifice my entire body, I would do so joyfully." God heard Isaac's remark and took note of it. He would one day test Abraham with just such a command...

Another midrash (quoting from Sanhedrin 89b) says that the sacrifice of Isaac was similar to God's test of the prophet Job. One day the angels came to minister before God and Satan was among them. The LORD said to Satan, "From where have you come?" Satan answered the LORD and said, "From going to and fro on the earth, and from walking up and down on it" (Job 1:7). And the LORD said to Satan, "Have you considered my servant Abraham, that there is none like him on the earth, a blameless and upright man, who fears God and turns away from evil?" Then Satan answered the LORD and said, "Does Abraham fear God for no reason? He had no sons for a long time and he built altars to please you, but after his request for a child was granted, he has long forgotten you. He sacrificed many cattle for a feast for Isaac, but he did not offer you a gift of thanks. Now many years have passed since then and he has yet to offer you a single sacrifice!" God answered that Abraham had made the feast in honor of his son, yet if He asked him to kill his son for the sake of God, he would gladly do so. That is what the words, "After these things God tested Abraham" means: after Satan's words of challenge were uttered, God asked Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. Rashi suggests that God prefaced the test with the word "please" (i.e., "Please take [קַח־נָא] your son, your only son, whom you love, even Isaac, and go to the land of Moriah and offer him up as a burnt offering." God modified His request with "please" [נָא] because the sacrifice of Isaac was not a command, and therefore Abraham was in a position to refuse.

Immediately after Abraham agreed to fulfill God's will, Satan began scheming of ways to defeat him. He placed numerous obstacles in Abraham's way to prevent him from fulfilling God's request, such as causing a surging river to appear directly on the path. He whispered into Isaac's ears that Abraham had gone insane. He tried to make Abraham question whether he had actually heard the voice of God. He disguised himself as an old man to Abraham who insinuated that Abraham had listened to a devil rather than God. Satan later disguised himself as a distressed Isaac and appeared to torment Sarah, hoping that she would somehow intervene and divert Abraham's mission. Throughout the journey to Moriah, Satan tried his best to dissuade Abraham, but God gave him grace to prevail (for more on this, see the "Midrash of the White Ram").

Other commentators speculate as to whether there was an "Ishmael connection" with the Akedah. According to Rashi, the sacrifice of Isaac was middah keneged middah ("like for like") justice applied to Abraham's unjust eviction of Hagar and his firstborn son. After all, despite his wealth and power, Abraham had sent them away to a certain death in the desert.... Indeed, Isaac later seemed to understand this, and many of his spiritual encounters with God occurred at Beer-lehai-roi, the place where Ishmael was first named - and later abandoned.

I should add that Abraham's test was also Sarah's test. Abraham realized he would have to gain Sarah's assent to let Isaac go off to Moriah, so he convinced her that sending Isaac to Shem's school would be the best thing for him. Sarah was apprehensive and clothed her son with special garments. She followed the men as far as Hebron, where Abraham finally told her to turn back. "Who knows if I shall ever look upon you again?" she said in parting to her son. It is a provocative thought that Sarah - not Isaac - was the real victim of the Akedah. She, not Isaac, is the one who died, after all. Jewish tradition has associated the cries of Sarah with the blasts of the shofar during Rosh Hashanah. The broken notes of the shofar are thought to recall her crying for her son (for more on this, see "The Akedah of Sarah").

Many commentators link the idea of a test (i.e., nissayon: נִסָּיוֹן) with that of a "banner" or "miracle" (i.e., nes: נֵס). Since God already knows the outcome of the test, its purpose is to "raise up" the righteous by lifting them up to a new spiritual level. In other words, the test is for the individual's benefit - certainly not to impart any new information to God. The sages note that God tests someone to enable him or her to become aware of their own capabilities (or limitations). Testing is therefore inherently soul-building. In addition, God tests people in order to demonstrate their capabilities to others. In the case of Abraham, the test of the Akedah functioned as a "banner" of his righteousness and faithful obedience. He is rightly regarded as the "father of faith" to all who believe (Rom. 4:11,16).

"On the Third Day..."

"On the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes and saw the place from afar" (Gen. 22:4). The midrash says that God deliberately prolonged the journey so that the nations should not later claim, "Abraham only sacrificed his son because he was taken by surprise when God gave him the command. No man would ever agree to an order to slaughter his own son, provided he were given ample time for reflection." Therefore God gave him three full days to consider the matter, and during that entire time Satan did his best to convince both Abraham and Isaac that it was a mistake to continue on their way.

Nonetheless Abraham and Isaac pressed on and traveled together. On the third day, Abraham saw a mountain bathed in a light that extended from earth to heaven, with the Shekhinah Glory resting above it. He then asked Isaac, "What do you see?" Isaac answered, "I see a lovely hill with a beautiful cloud rising over it." Abraham then asked his two servants what they saw, and they answered they saw nothing. Abraham then told his two servants, "Stay here with the donkey; I and the boy will go over there and worship and we will return to you" (Gen. 22:5). According to midrash, since the two servants could not see the Shekhinah on the mountain, Abraham left them with the donkey. Then the two servants began to quarrel . Ishmael said that after Isaac's sacrifice he would be heir, whereas Eliezer said that he would be the heir. A heavenly voice finally said, "Neither of you will be heir, for in Isaac shall the Seed come."

Notice that Abraham had told the servants that "we will return to you" (וְנָשׁוּבָה אֲלֵיכֶם). Rashi states this was a prophecy of Isaac's resurrection, though other sages say that it meant that Abraham would return with his ashes. The New Testament comments that this was evidence that Abraham believed that God would resurrect Isaac from the dead (Heb. 11:17-19). Abraham believed that - despite the coming sacrifice of his son - both of them would return.

"They Went Together..."

"And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering and laid it on Isaac his son. And he took in his hand the fire and the knife. So they went both of them together" (Gen. 22:6). Isaac carried the wood and Abraham carried the fire and knife. According to Jewish tradition, Isaac was a 37 year old man who suspected that he was indeed going to be offered up as a sacrifice (Seder Olam Rabbah). Nevertheless, he did not flee from his father but continued to trust in him... They ascended the mountain together...

But Isaac needed to make sure of what was really happening. He needed to understand what was being asked of him. "And Isaac said to his father Abraham, "My father!" And he said, "Here am I, my son." And he said, "Behold, the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?" (Gen. 22:7). This is the first word of dialog recorded over the three day journey... It is hard to imagine Isaac's pathos during this exchange. The grammar of the dialog is somewhat odd. Why does the Torah say that Isaac said to his father Abraham? And why does Isaac call out to Abraham as my father (אָבִי)? You can almost hear Isaac's faltering words to his father: "he said ... [ silence ] ... he said, 'my father....' he said, '...but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?' (for more on this, see the "Passion of Isaac"). "Isaac called out to his father, "Father," in order to arouse his mercy, not so that Abraham would be overcome with emotion and change his plans, but rather so that his love would be offered upon the altar" (Imrei Emes).

Abraham replied, "God will provide for himself the lamb for a burnt offering, my son." So they went both of them together (Gen. 22:8). Notice that the Hebrew could be read: "God will provide the lamb for the burnt offering -- my son!"(ירְאֶה־לּוֹ הַשֶּׂה לְעלָה בְּנִי) - making it plain that Isaac was himself to be offered upon the altar. According to midrash, upon hearing this, Isaac put his face between his hands and wept. "Is this the Torah about which you spoke to mother?" he sobbed. When Abraham heard this, he wept also. But Isaac controlled himself and sought to comfort his father: "Do not feel distressed, my father. Fulfill your Creator's will through me! May my blood be an atonement for the future Jewish people" (Bereshit Rabbah). The Torah then repeats the phrase, "and they both walked on together," indicating that Isaac had accepted his sacrificial death. Isaac had yielded his strength in perfect surrender and trust to his father, while Abraham held his beloved son's hand, afraid that he might lose courage and run away.

Love's Great Sacrifice

"When they came to the place of which God had told him, Abraham built the altar there and laid the wood in order and bound Isaac his son and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood" (Gen. 22:9). Here we are reaching the climax of the narrative. Abraham built the altar on Moriah and "arranged the wood in order." According to tradition, this altar was in the very same place as the one built by Adam and later destroyed by the flood. It was rebuilt by Noah but later destroyed by Nimrod after the Dispersion of Babel. Now it was rebuilt by Abraham. Isaac presumably watched all of this in dreadful anticipation, yet he submitted to his father in complete trust. The aged Abraham then "bound Isaac his son" (וַיַּעֲקד אֶת־יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ) and carefully laid him on the altar, "on top of the wood." According to the Talmud, Isaac asked his father to make the knots on his hands and feet tighter - not out of fear that he would change his mind and begin to resist - but in order to encourage his father to offer the sacrifice properly (Bereshit Rabbah 56:8). Since kosher slaughtering required the sacrificial victim's throat to be cut quickly, Isaac wanted to ensure that he did not flinch and thereby invalidate the sacrifice... Like the Suffering Servant who would come after him, Isaac "set his face like a flint" to fulfill God's will (Isa. 50:7).

Isaac kept his eyes directed toward heaven as he lay tightly bound and motionless upon the altar. He awaited the final blow and wanted it to fall with love and obedience within his heart. It was to be a shared sacrifice between the beloved son and his father. Finally "Abraham stretched out (שׁלח) his hand and took the knife to slaughter (i.e., לִשְׁחט, from shechitah) his son" (Gen. 22:10). The Talmud says that when Abraham "stretched out" his hand, he briefly examined the knife to determine if it was ritually fit, and this delay was the precise moment when the Angel of the LORD (מַלְאַךְ יהוה) called to him from heaven and said, "Abraham, Abraham!" (Gen. 22:11). (Note the repetition of the name "Abraham" during this second call.) According to various midrashim, when Abraham put his knife to his son's neck, Isaac's soul departed from him, but it returned when the Angel of the LORD said, "Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him, for now I know that you fear God, seeing you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me" (Gen. 22:12). Abraham then immediately released Isaac and recited the blessing, "Blessed are You, LORD, who revives the dead" (בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יהוה מְחַיֶּה הַמֵּתִים).

The Lamb of God

"And Abraham lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, behind him was a ram, caught in a thicket by his horns. And Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering in place of his son" (Gen. 22:13). The ram was offered tachat (תַּחַת, lit. "underneath" or "in exchange") for Isaac, which is the key idea of substitutionary atonement (i.e., the Korban Principle). The midrash says that throughout each step of the sacrifice of the ram, Abraham prayed, "May God regard this as though it were my son..." Abraham then said, "Master of the Universe, when you commanded me to offer Isaac as a sacrifice, I could have contradicted you, but I suppressed all arguments in order to do Your will. If my sons sin in future times, remember Isaac's binding, suppress your anger, and forgive them." Here again is the Rosh Hashanah connection. As the Talmud says, "The Holy One, blessed be He, said, 'Sound before Me the ram's horn so that I may remember on your behalf the binding of Isaac and account it to you as if you had bound yourselves before Me'" (Rosh Hashanah 16a).

"The Mount of the LORD..."

So Abraham called the name of that place, Adonai Yireh ("The LORD will provide"); as it is said to this day, "On the mount of the LORD it shall be provided" (Gen. 22:14). Interestingly, the name Moriah (מוריה) comes from the same verb ra'ah (ראה), "to see" (with the divine Yah- [יהּ] suffix). There is a play on words here. It was at Moriah (lit. "seen by YHVH") that Abraham called the LORD Adonai Yireh (יְהוָה יִרְאֶה), "the LORD will see [our need]" in reference to the provision of substitutionary sacrifice in Isaac's place. Mount Moriah (i.e., Zion) is central to Jewish history. It is the place where Jacob dreamed of the ladder to heaven, it is the site of the Holy Temple, and it is the place where Yeshua our Messiah was crucified and raised from the dead. The account of the Akedah may rightly be regarded as the "Gospel according to Moses" (Luke 24:27; John 5:46). Therefore it became an adage after the sacrifice of Isaac to say, "On the mount of the LORD it shall be provided." אֱלהִים יִרְאֶה־לּוֹ הַשֶּׂה / Elohim yireh-lo haseh ("God Himself will provide a lamb").

Reaffirmation of Love

As the smoke of the sacrificial ram ascended in place of Abraham's son, the Angel of the LORD called to Abraham a second time from heaven and said, "By myself I have sworn, declares the LORD, because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, I will surely bless you, and I will surely multiply your offspring as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore. And your offspring shall possess the gate of his enemies, and in your offspring shall all the nations of the earth be blessed, because you have obeyed my voice" (Gen. 22:15-18). The phrase, "by myself have I sworn" is the most solemn oath God could make and must be regarded as an inviolable vow (see also Isa. 45:23, Jer. 22:5, 49:13, 51:14; Amos 6:8; Heb. 6:13-14). Because of Abraham's great faith and obedience ("because you have obeyed my voice"), God personally vowed to establish His covenant with Abraham and his descendants forever.

The promise of the "Gospel in the Garden," originally given to Adam and Eve, was preserved through godly line of Seth to Noah, and then again (after the Flood) from Shem to the promised Seed of Abraham. Isaac was a picture of the greater Seed to come, the Eternal Redeemer who would be sacrificed as a blessing to all the families of the earth" (Gen. 12:3). God's plan was always to bring the Promised Redeemer to Moriah for the salvation of the human race...

Resurrection of Isaac...

"So Abraham returned to his young men, and they arose and went together to Beersheba. And Abraham lived at Beersheba" (Gen. 22:19). There is a tradition that Abraham actually went through with the act of sacrifice on Moriah. After all, the subsequent text shows Abraham returning alone from the mountain (the verb describing Abraham's return is singular). So where was Isaac? According to this tradition he was left "as ash" upon the altar -- though later God miraculously brought him back to life. In other words, Isaac suffered martyrdom and was resurrected from the dead. Another midrash says that though Abraham did not actually go through with the sacrifice (his hand was stayed by the Angel), the trauma caused Isaac to flee from his father and to seek refuge with Noah's son Shem (who was considered "Malki-Tzedek" and the high priest of Salem). The Midrash Hagadol states, "Although Isaac did not die, Scripture regards him as though he had died. And his ashes lay piled on the altar. That is why the text mentions Abraham and not Isaac."

"I will go..."

It is fascinating that we hear nothing about Isaac after the Akedah until we read of Abraham's commissioning of Eliezer to find his divinely appointed bride. Isaac is not even mentioned during the time of the death of his mother Sarah. Is this an analogy of the hiddenness of Yeshua to the Jewish people? Abraham returned to his servants alone, while Isaac remained out of sight until a Gentile bride (Rebekah) was brought to him. Rebekah was willing to leave her family - all that she knew - based on an "otherworldly" promise. Her response to the invitation was simply: "I will go"(Gen. 24:58). This courageous willingness was likewise a characteristic of Abraham who was willing to leave his homeland in search of the greater things of God. Like Abraham, Rebekah was ger v'toshav - a "stranger and a sojourner" - who left everything behind in order to become part of God's chosen family... She is therefore a "picture" of those who likewise say "I will go" to become joined to our beloved Messiah.

Note: This entry is still being written, with more to come, if it pleases God. Shalom for now, chaverim!

|