|

July 2010 Updates

As the Day draws near...

[ The following entry is based on a comment Rashi made regarding the "Days of the Messiah" in this week's Torah reading (parashat Eikev). I hope you find it helpful... ]

07.30.10 (Av 19, 5770) Our actions invariably reveal what we are believing about the nature of reality. We will live what we believe... Put the other way around, what we believe will determine what we do. Nearly all of our conscious intentions are future-directed. We assume that the future will resemble the past, and therefore we make our plans and set our agendas. And yet to what end? What is the purpose of our lives? Where are your actions taking you?

Questions like these concern your personal philosophy of life. Every person makes choices based on their vision and expectation of a future good. Every person therefore lives by a creed that speaks toward the future.... Sadly, many people live for the immediate moments of life: cheap thrills, fast food, and mindless entertainment. "Let's eat and drink, for tomorrow we die" (1 Cor. 15:23). Others may enjoy fine art, reading, and learning - hoping thereby to improve themselves. Most people live in order to love others, friends and family... But apart from God, none of these otherwise good things will ultimately satisfy our hearts. "Disordered love" comes from setting the heart's affections on the transitory, the ephemeral, and the unabiding; but God has set eternity within our hearts (Eccl 3:11). The Lord has "wired" us to experience discontent when our heart's deepest need goes unmet.

On a larger scale, philosophers have asked whether life itself - all of it - has any meaning or purpose. "Why is there something rather than nothing - and for what reason?" Is the universe essentially a random set of events, or is there some overarching purpose and design to everything? Is history linear or cyclical? Does it have a goal or destination, or is this entirely unknowable to us? Are human beings evolving - and if so, to what? Is there a spiritual dimension to reality, or is everything causally determined by matter and motion? Do we have "free will" or are we entirely conditioned to do what we do? Various answers have proposed to deal with these questions over time, including mythological polytheism (e.g., Zoroastrianism, Egyptian/Greek mythology, animism, paganism), cyclical impersonalism (e.g., Hinduism, Jainism, Taoism, reincarnationism, Stoicism), various types of materialism (e.g., scientific naturalism, pragmatism, evolutionism, nihilism), humanism (Buddhism, secular humanism, atheistic existentialism), romantic idealism (Marxism, Hegelianism), mysticism (theosophy, new age thinking, popular Kabbalah), and so on.

The traditional Jewish view of history may be called (for lack of a better term) "monotheistic personalism." There is one Supreme God who is the personal Creator and Ruler of all that exists. God is both immanent (sustaining creation) and transcendant (above creation). This God has a Name (YHVH), a mind, and a moral, purposive will that imbues all of creation. God is LORD over all time and space, the King of Glory, who is Master of all possible worlds. Since God knows and providentially controls everything, human history is a controlled process that leads to a destination. History is therefore progressive and eschatological - leading to a future goal.

But where is everything "going?" In particular, what is the destiny of the human race? If there is a characteristically "Jewish philosophy of history," it decidedly centers on the vision of Zion as the restoration and fulfillment of the lost paradise of Eden. The relationship between Adam and God will be fully restored in the coming theocratic utopia called "heavenly Jerusalem." This is heaven, the place of our deepest longing:

בִּלַּע הַמָּוֶת לָנֶצַח

וּמָחָה אֲדנָי יהוה דִּמְעָה מֵעַל כָּל־פָּנִים

bil·la ha·ma·vet la·ne·tzach,

u'ma·chah Adonai Elohim dim·ah mei·al kol pa·nim

"He will destroy death forever.

The Lord GOD will wipe the tears away from all faces" (Isa. 25:8)

Download Reading Card

As I've mentioned before, the word "Zion" is mentioned over 160 times in the Scriptures. That's more than the words faith, hope, love, and countless others... And since Zion is a poetic form of the word Jerusalem, the number of occurrences swells to nearly 1,000! It is therefore not an overstatement to say that God Himself is a Zionist.... "Out of Zion, the perfection of beauty, God shines forth" (Psalm 50:2). Zion represents the rule and reign of God in the earth and is therefore synonymous with the Kingdom of God. The entire redemptive plan of God -- including the coming of the Messiah Himself and our very salvation -- is wrapped up in the concept of Zion. It is the "historiography" of God -- His philosophy of history, if you will.

In a sense, Zion is the heart of the Gospel message and the focal point of God's salvation in this world. Zion represents our eschatological future -- our home in olam haba (the world to come). Even the new heavens and earth will be called Jerusalem -- "Zion in her perfection" (Rev. 21). "This is what Adonai Tzeva'ot says: I am very jealous for Jerusalem and Zion, but I am very angry with the nations that feel secure" (Zech. 1:14-15). "For Zion's sake I will not keep silent, for Jerusalem's sake I will not remain quiet, till her righteousness shines out like the dawn, her salvation like a blazing torch" (Isa 62:1). "The builder of Jerusalem is God, the outcasts of Israel he will gather in... Praise God, O Jerusalem, laud your God, O Zion" (Psalm 147:2-12).

The outworking of humanity's history is essentially a conflict between good and evil. It traces back to paradise lost and the eventual construction of Bavel in ancient Shinar, where Nimrod attempted to collectivize humanity under autocratic rule. Yeshua referred to it (among other things) as a conflict between the Kingdom of God (מַלְכוּת אֱלהִים) and the kingdom of Satan (John 8:34-6). The Apostles likewise spoke of "children of darkness" and "children of light" (Eph. 5:8; Col. 1:13, 1 Thess. 5:5, etc.). Politically speaking, St. Augustine described the cosmic conflict as one between the "City of Man" and the "City of God." World politics nearly always involves some form of violence against those who belong to God (Matt. 11:12).

The Tanakh and New Testament represent "sacred history" (though not necessarily chronologically understood). It is thematic and spiritual history, though it is rooted in historical fact, not myth and legend. For example, the findings of archaeology regularly reinforce historical events mentioned in the Scriptures. Our faith is based on historical, empirical, verifiable evidence.

Jewish tradition has long held that human history (olam hazeh) would endure for 6,000 years - from the time of the impartation of the neshamah (soul) to Adam in the Garden of Eden to the coming of the Messiah. There were two primary arguments for this view of history.

First, the sages argued that a "divine day" (יוֹם) equaled 1,000 years based on Psalm 90:4: "A thousand years (אֶלֶף שָׁנִים) in your sight is as a day (i.e., k'yom: כְּיוֹם)." They reasoned that since man was made in the image of God, and the Torah describes six days of creation followed by a day of divine rest, mankind (as a whole) was therefore allotted 6 x 1,000 years (i.e., 6,000) for "works" to be established in the world, followed by a 1,000 year Shabbat (Sanhedrin 97a, Rosh Hashana 31a). The ancient Seder Olam Rabbah (c. 240) catalogs historical events from the start of Creation according to the 6,000 years of history. Humanity will have his time of reign on earth for 6,000 years and then the Messiah will begin his reign in the 7th millennium, a "Sabbath" of sacred history. Later midrash goes along with this basic outline: "Six eons for going in and coming out, for war and peace. The seventh eon is entirely Shabbat and rest for life everlasting" (Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer). The Apostle Peter may also have had this outline in mind when he wrote, "With the Lord one day is as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day" (2 Pet. 3:8; Psalm 90:4).

Second, the Jewish mystics argued that since there are 6 Alephs (א) in the very first verse of the Torah, and each Aleph (אלף) represents 1,000, there must be 6,000 years of human history. The Zohar states, "The redemption of Israel will come about through the mystic force of the letter "Vav" [the sixth letter of the Aleph-bet, corresponding to the sixth Aleph] in the sixth millennium. Happy are those who will be left alive at the end of the sixth millennium to enter the Shabbat, which is the seventh millennium; for that is a day set apart for the Holy One on which to effect the union of new souls with old souls in the world" (Zohar, Vayera 119a).

So according to both the rabbis and the mystics, human history will last for 6,000 years - 1,000 years for each day of creation - followed by a 1,000 year "Shabbat" that represents the Messianic Age of global and universal peace. After the Messiah appears, there will be peace on earth, and all the promises of God given through the prophets will be fulfilled.

It is worth noting that in the discussion from the Talmud, the 6,000 years of human history are divided into three epochs of 2,000 years each. The period of "tohu" occurred from the time of the fall of Adam until the call of Abraham; the period of "Torah" occurred from Abraham until the time of the destruction of the Second Temple, and the period of the "Messiah" refers to the time when the Messiah could appear before the Kingdom is established in Zion. The time immediately preceding the appearance of the Messiah will be a time of testing in which the world will undergo various forms of tribulation, called chevlei Mashiach (חֶבְלֵי הַמָּשִׁיחַ) - the "birth pangs of the Messiah" (Sanhedrin 98a; Ketubot, Bereshit Rabbah 42:4, Matt. 24:8). Some say the birth pangs are to last for 70 years, with the last 7 years being the most intense period of tribulation -- called the "Time of Jacob's Trouble" / עֵת־צָרָה הִיא לְיַעֲקב (Jer. 30:7). The climax of the "Great Tribulation" (צָרָה גְדוֹלָה) is called the great "Day of the LORD" (יוֹם־יהוה הַגָּדוֹל) which represents God's wrath poured out upon a rebellious world system. On this fateful day, the LORD will terribly shake the entire earth (Isa. 2:19) and worldwide catastrophes will occur. "For the great day of their wrath has come, and who can stand?" (Rev. 6:17). The prophet Malachi likewise says: "'Surely the day is coming; it will burn like a furnace. All the arrogant and every evildoer will be stubble, and that day that is coming will set them on fire,' says the LORD Almighty. 'Not a root or a branch will be left to them'" (Mal. 4:1). Only after the nations of the world have been judged will the Messianic kingdom (מַלְכוּת הָאֱלהִים) be established upon the earth. The remnant of Israel will be saved and the 1000 year reign of King Messiah will then commence (Rev. 20:4).

|

Note: Some Christian scholars such as the late Dr. Clarence Larkin have divided the days somewhat differently and have added an additional "day" based on the coming eternal state of the "Heavenly Jerusalem." Hence Larkin's depiction of the Eight Days of Creation:

|

As for the exact timing of these events, "no one knows the day or hour." In fact, various Jewish sages have argued for "missing years" in the prophetic calendar (due to periods of exile or other factors) and therefore they say that the Day of the LORD may be delayed on account of national sins. For example, based on the gematria of the first two words of a verse from this week's parashah (i.e., וְהָיָה עֵקֶב, Deut. 7:12) Rashi explained that the 2,000 years of the Days of Messiah actually began 198 after the destruction of the Second Temple. "198 years after the destruction of the Temple the bells of the Messiah will be heard" (i.e., the days of the Messiah would begin). According to Rashi, the delay was the result of Israel's sin. (On the other hand, many ultra-Orthodox Jews believe they can "hasten" the Messiah's appearance through acts of teshuvah: "Moshiach Now!").

Since Jewish tradition states that the "days of Messiah" began after 4,000 years of history (i.e., four "days"), we can better understand the Messianic fervor among the Jews during the first century in Judea. The Essenes were awaiting the advent of the "Teacher of Righteousness" and the "Zealots" wanted to establish the Kingdom of God by force of arms. Even the common people of Israel were full of expectation that the Messiah would soon appear to redeem captive Israel. It was in this context, in the "fulness of time" (Gal. 4:4), that Yeshua began His earthly ministry as the Suffering Servant who redeemed us from the "curse of the law" (Gal. 3:13).

Messianic Hope: The King of the Jews

The Medieval rabbi and scholastic philosopher Maimonides (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, or "Rambam") is considered to be a mainstream voice of traditional Judaism. Maimonides' "Twelfth Principle" of the Jewish faith is his affirmation that the Messiah is coming to restore Israel to greatness beyond that known in the days of King Solomon. "I believe with complete faith in the coming of the Messiah, and though he may delay, nevertheless I wait for his coming every day." The following statement by Maimonides is probably the definitive rendering of the traditional Jewish view on the subject:

If a king will arise from the House of David who is learned in Torah and observant of the mitzvot, as prescribed by the written law and the oral law, as David his ancestor was, and will compel all of Israel to walk in the way of the Torah and reinforce the breaches; and fight the wars of G-d, we may, with assurance, consider him the Messiah. If he succeeds in the above, builds the Temple in its place, and gathers the dispersed of Israel, he is definitely the Messiah. ... If he did not succeed to this degree or he was killed, he surely is not the redeemer promised by the Torah..." (Mishneh Torah).

The concept of the King Messiah, the "Anointed One" who would one day come to deliver his people from oppression at the beginning of an era of world peace has been the sustaining hope of the Jewish people for generations. King Messiah is the instrument by whom God's kingdom is to be established in Israel and in the world. This hope runs throughout the entire Tanakh. According to rabbinical Judaism (following Maimonides), this Messiah figure is not divine, though he certainly has divine powers and attributes. Indeed, he functions as Israel's Savior who would be empowered by God to:

- Restore the Kingdom of David (Jer. 23:5, Jer 30:9, Ezek. 34:23)

- Restore the Temple in Zion (Isa. 2:2, Micah 4:1, Zech. 6:13, Ezek. 37:26-28)

- Regather the exiles (Isa. 11:12, 43:5-6, 51:11)

- Offer the New Covenant to Israel (Jer. 31:31-34)

- Usher in world peace and the knowledge of the true God (Isa. 2:4; 11:9). This will include the entire world speaking Hebrew (Zeph. 3:9).

- "Swallow up" death and disease (Isa. 25:8)

- Raise the dead to new life (Isa. 26:19)

- Spread Torah knowledge of the God of Israel, which will unite humanity as one. As it says: "God will be King over all the world -- on that day, God will be One and His Name will be One" (Zech. 14:9)

Note: In the Tanakh, the key passage on which the idea of the Messianic king who would rule in righteousness and attain universal dominion is found in Nathan's oracle to David (2 Sam. 7:11 ff). This covenant cannot have been fulfilled by Solomon, and therefore the Seed of which the oracle refers is another anointed King who would sit on the throne forever and ever. (Contrary to the heresies of "Covenant Theology" and "amillenialism," Yeshua is not presently sitting on the throne of David as Zion's King, and therefore the Jewish hope of the Messiah has not been fulfilled, just as the New Covenant terms have not yet been entirely fulfilled.)

Dual Aspect of Mashiach

How could the Jewish sages have missed the advent of Messiah, especially in light of the fact that their own eschatology expected the Messiah to appear some 2,000 years after the Torah was given to Israel (i.e., the first century AD)? Even the Babylonian stargazers were able to discern the appointed time (Matt. 2:1-2).

Perhaps the sages got confused about how to interpret the Hebrew prophets. This shouldn't surprise us, for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that the prophets were regularly misunderstood and persecuted by the sages in Jewish history. Still, the sages might have missed the coming of Yeshua because there seems to be two distinct pictures of the Messiah given in the visions of the prophets. On the one hand, Messiah is portrayed as a great king, deliverer, and savior of the Jewish people who comes in triumph "in the clouds" (Dan. 7:13), but on the other he is depicted as riding a donkey, lowly and humble (Zech. 9:9), a suffering servant, born in lowliness, despised and rejected of men. These two images of Messiah eventually lead to various oral traditions that there would be two Messiahs: Messiah ben Joseph (מָשִׁיחַ בֶּן־יוֹסֵף) and Messiah ben David (מָשִׁיחַ בֶּן־דָוִד).

Mashiach ben Yosef is identified with the Suffering Servant, of whom the patriarch Joseph prefigured (and of whom Isaiah plainly spoke in his four "Servant Songs"). In some traditions of Judaism, Mashiach ben Yosef is recognized as a forerunner and harbinger of the final deliverer, Mashiach ben David. Ben Yosef suffers for the sins of Israel and ends up getting killed in the battle against evil (Isaiah 53). Of course Christians see Yeshua as the prophesied "Man of Sorrows" and Suffering Servant who would bear the sins of many.

Mashiach ben David, on the other hand, is identified as the great military ruler and King of Israel of whom King David prefigures. This greater "son of David" will regather the exiles, set up the Temple, and deliver Israel from all her enemies. This is the Messiah that the sages of Judaism have long been expecting. Christians believe Yeshua the Messiah in His second coming will completely fulfill this description of Mashiach ben David.

In other words, since the prophecies concerning the Messiah are twofold or "dual aspect," we discern that they would be fulfilled in two distinct ways. Yeshua is both Mashiach Ben Yosef (the Suffering Servant - at His first coming) and Mashiach Ben David (the Reigning King - at His second coming). He is also the Anointed Prophet, Priest, and King as foreshadowed by other me'shichim in the Tanakh. Both traditional Jews and Christians are awaiting for the appearance of the Messiah, though Christians, of course, will welcome Yeshua back!

According to this general framework of history, we are currently living in the "days of the Messiah," just before the time of great worldwide tribulation that will lead to the prophesied acharit hayamim (אַחֲרִית הַיָּמִים), or the "End of Days." This is the age in which the spirit of the Messiah is available to all. These are "days of God's favor" that are ending soon. According to traditional Jewish sources (Pesachim 54b; Midrash Tehilim 9:2), no one knows the exact time when the Messiah will appear -- though there are some hints. The condition of the world during the end of days will be grossly evil (2 Pet. 3:3; 2 Thess. 2:3-4, 2 Tim. 3:1-5). The world will undergo various forms of tribulation, collectively called chevlei Mashiach (חֶבְלֵי הַמָּשִׁיחַ) - the "birth pangs of the Messiah" (Sanhedrin 98a; Ketubot, Bereshit Rabbah 42:4, Matt. 24:8). Some sages say the birth pangs will last 70 years, with the last 7 years as the most intense period -- the "Time of Jacob's Trouble" / עֵת־צָרָה הִיא לְיַעֲקב (Jer. 30:7). Just before the arrival of Yeshua as Mashiach ben David, a period of tribulation and distress for Israel will occur. After this "great tribulation" period, however, Yeshua will usher in Yom YHVH, the "Day of the LORD," and the sabbatical millennium, the 1000 year reign of King Messiah will commence (Rev. 20:4).

קָרוֹב יוֹם־יהוה הַגָּדוֹל קָרוֹב וּמַהֵר מְאד

קוֹל יוֹם יהוה מַר צרֵחַ שָׁם גִּבּוֹר׃

ka·rov yom Adonai hag·ga·dol, kar·ov u'ma·her me·od,

kol yom Adonai mar tzo·re·ach sham gib·bor

"The great day of the LORD is near, near and hastening fast;

the sound of the day of the LORD is bitter; the mighty man cries aloud." (Zeph. 1:14)

Although "Day of the LORD" is often associated with Tishah B'Av and the catastrophic destruction of the Jewish Temple, the words of the prophets were only partially fulfilled, and there awaits another Day coming when God will terribly shake the entire earth (Isa. 2:19). "For the great day of their wrath has come, and who can stand?" (Rev. 6:17). The prophet Malachi likewise says: "'Surely the day is coming; it will burn like a furnace. All the arrogant and every evildoer will be stubble, and that day that is coming will set them on fire,' says the LORD Almighty. 'Not a root or a branch will be left to them'" (Mal. 4:1). For those who are godless, the great Day of the LORD is a time of horrific judgment, but for those who belong to the LORD, it represents a day of victory and great blessing. Regarding that day the prophet Malachi said, "Then you will trample down the wicked; they will be ashes under the soles of your feet on the day when I do these things" (Mal. 4:3).

כַּעֲבוֹר סוּפָה וְאֵין רָשָׁע וְצַדִּיק יְסוֹד עוֹלָם

ka·a·vor su·fah v'ein ra·sha, v'tzad·dik ye·sod o·lam

"When the storm has swept by, the wicked are gone,

but the righteous stand firm forever." (Prov. 10:25)

Ultimately the Great Tribulation period is redemptive and healing (called yissurei ahavah, "the troubles of love"). The prophets wrote that Zion will go through labor and then give birth to children (Isa. 66:8). Thus the Vilna Gaon wrote that the geulah (national redemption) is something like rebirth of the nation of Israel. This accords with the prophetic fulfillment of Yom Kippur as the Day of Judgment and time of Israel's national conversion. In the verse from prophet Jeremiah regarding the "Time of Jacob's Trouble," it's vital to see the goal in mind - "yet out of it he is saved" (וּמִמֶּנָּה יִוָּשֵׁעַ). When Yeshua returns to Zion, all Israel will be saved (Rom. 11:26). The sages note that childbirth is a time of radical transition and struggle for the baby -- from the time of relatively peaceful existence within the womb into the harsh light of day -- and therefore a similar transition between this world and the Messianic world to come is about to take place....

וְהָיָה יהוה לְמֶלֶךְ עַל־כָּל־הָאָרֶץ

בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא יִהְיֶה יהוה אֶחָד וּשְׁמוֹ אֶחָד

ve·ha·yah Adonai le·me·lekh al kol ha·a·retz,

ba·yom ha·hu yi·he·yeh, Adonai e·chad u·shmo e·chad

"Then the LORD will be king over the whole world. On that day

there shall be one LORD with one name." (Zech. 14:9)

The Fear of the LORD

[ The following concerns this week's Torah reading, parashat Eikev. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here... ]

07.28.10 (Av 17, 5770) What does it mean to "fear" God? Does it mean that we should be afraid of God's disapproval of us? Should we live in dread over the prospect of future judgment for our sins? In order to consider some of these questions, let's consider a verse from this week's Torah portion:

וְעַתָּה יִשְׂרָאֵל מָה יהוה אֱלהֶיךָ שׁאֵל מֵעִמָּךְ כִּי אִם־לְיִרְאָה

אֶת־יהוה אֱלהֶיךָ לָלֶכֶת בְּכָל־דְּרָכָיו וּלְאַהֲבָה אתוֹ וְלַעֲבד

אֶת־יהוה אֱלהֶיךָ בְּכָל־לְבָבְךָ וּבְכָל־נַפְשֶׁךָ׃

ve·at·tah Yis·ra·el: mah Adonai E·lo·he·kha sho·el me·im·makh, ki im le·yir·ah

et Adonai E·lo·he·kha, la·le·khet be·khol de·ra·khav u·le·a·ha·vah o·to. ve·la·a·vod

et Adonai E·lo·he·kha, be·khol le·vav·kha uv·khol naf·she·kha

"And now, Israel, what does the LORD your God require of you, but to fear

the LORD your God, to walk in all his ways, to love him, to serve

the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul" (Deut. 10:12)

In this summary statement of what the LORD requires of us, the fear of the LORD (i.e., yirat HaShem: יִרְאַת יהוה) is mentioned first. First we must learn to properly fear the LORD and only then will we be able to walk (לָלֶכֶת) in His ways, to love (לְאַהֲבָה) Him, and to serve (לַעֲבד) Him with all our heart and soul. Again, the requirement to fear the LORD your God (לְיִרְאָה אֶת־יהוה) is placed first in this list...

Indeed, "the fear of the LORD is said to be the beginning of wisdom (רֵאשִׁית חָכְמָה)." Without fear of the LORD, you will walk in darkness and be unable to turn away from evil (Psalm 111:10; Prov. 1:7; 9:10; 10:27; 14:27, 15:33; 16:6). The Scriptures plainly declare that "the fear of the LORD leads to life" (יִרְאַת יְהוָה לְחַיִּים, lit. "is for life"):

יִרְאַת יהוה לְחַיִּים וְשָׂבֵעַ יָלִין בַּל־יִפָּקֶד רָע

yi·rat Adonai le·cha·yim, ve·sa·ve·'a ya·lin bal yi·pa·ked ra'

"The fear of the LORD leads to life, and the one who has it rests satisfied

and is untouched by evil" (Prov. 19:23)

The word translated "fear" in many versions of the Bible comes from the Hebrew word yirah (יִרְאָה), which has a range of meaning in the Scriptures. Sometimes it refers to the fear we feel in anticipation of some danger or pain, but it can also can mean "awe" or "reverence." In this latter sense, yirah includes the idea of wonder, amazement, mystery, astonishment, gratitude, admiration, and even worship (like the feeling you get when gazing from the edge of the Grand Canyon). The "fear of the LORD" therefore includes an overwhelming sense of the glory, worth, and beauty of the One True God.

Some of the sages link the word yirah (יִרְאָה) with the word for seeing (רָאָה). When we really see life as it is, we will be filled with wonder and awe over the glory of it all. Every bush will be aflame with the Presence of God and the ground we walk upon shall suddenly be perceived as holy (Exod. 3:2-5). Nothing will seem small, trivial, or insignificant . In this sense, "fear and trembling" (φόβοv καὶ τρόμοv) before the LORD is a description of the inner awareness of the sanctity of life itself (Psalm 2:11, Phil. 2:12).

Abraham Heschel wrote, "Awe is an intuition for the dignity of all things, a realization that things not only are what they are but also stand, however remotely, for something supreme. Awe is a sense for transcendence, for the mystery beyond all things. It enables us to perceive in the world intimations of the divine, to sense the ultimate in the common and the simple: to feel in the rush of the passing the stillness of the eternal. What we cannot comprehend by analysis, we become aware of in awe" (Heschel: God in Search of Man). He continued by quoting, "The awe of God is the beginning of wisdom" (Psalm 111:10) and noted that such awe is not the goal of wisdom (like some state of nirvana), but rather its means. We start with awe and that leads us to wisdom. For the Christian, this wisdom ultimately is revealed in the love of God as demonstrated in the sacrificial death of His Son. The awesome love of God for us is the end or goal of Torah. We were both created and redeemed in order to know, love, and worship God forever.

According to Jewish tradition, there are three "levels" or types of yirah. The first level is the fear of unpleasant consequences or punishment (i.e., yirat ha'onesh: יִרְאַת הָענֶשׁ). This is perhaps how we normally think of the word "fear." We anticipate pain of some kind and want to flee from it. But note that such fear can also come from what you believe others might think about you. People will often do things (or not do them) in order to barter acceptance within a group (or to avoid rejection). Social norms are followed in order to avoid being ostracized or rejected. One implication of this type of fear is that "people will value justice not as a good but because they are too weak to do injustice with impunity" (Plato: Republic). As a thought experiment, would you act differently if you were given a magical ring that could make you invisible? Would the "freedom to do whatever you like with impunity" lead you to consider doing things you otherwise wouldn't do? If so, then you might be acting under the influence of this kind of fear....

The second type of fear concerns anxiety over breaking God's law (sometimes called yirat ha-malkhut: יִרְאַת הַמַּלְכוּת). This kind of fear motivates people to do good deeds because they are afraid God will punish them in this life (or in the world to come). This is the foundational concept of karma (i.e., the cycle of moral cause and effect). As such, this kind of fear is founded on self-preservation, though in some cases the heart's motive may be mixed with a genuine desire to honor God or to avoid God's righteous wrath for sin (Exod. 1:12, Lev. 19:14; Matt. 10:28; Luke 12:5). In the commandment not to curse the deaf or place a stumblingblock before the blind, for example, the Torah adds, "you shall fear the Lord your God" (Lev. 19:14). God does not wink at evil or injustice, and those who practice wickedness have a genuine reason to be afraid (Matt. 5:29-30; 18:8-9; Gal. 6:7-8). God is our Judge and every deed we have done will be made known: "Every man's work shall be made manifest: for the day shall declare it, because it shall be revealed by fire; and the fire shall try every man's work of what sort it is" (1 Cor. 3:13). "For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Messiah, so that each one may receive what is due for what he has done in the body, whether good or evil" (2 Cor. 5:10). When we consider God as the Judge of the Universe, "it is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God" (Heb. 10:31).

The third (and highest) kind of fear is a profound reverence for life that comes from rightly seeing. This level discerns the Presence of God in all things and is sometimes called yirat ha-romemnut (יִרְאַת הָרוֹמְמוּת), or the "Awe of the Exalted." Through it we behold God's glory and majesty in all things. "Fearing" (יִרְאָה) and "seeing" (רָאָה) are linked and united. We are elevated to the level of reverent awareness, holy affection, and genuine communion with God's Holy Spirit. The love for good creates a spiritual antipathy toward evil, and conversely, hatred of evil is a way of fearing God (Prov. 8:13). "For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God" (John 3:20-21). In relation to both good and evil, then, love (אַהֲבָה) draws us near, while fear (יִרְאָה) holds us back.

Back to our original verse. What does the word yirah mean in Deut. 10:12? Are we to regard it as fear or as awe? Should we fear God in the sense of being threatened by Him for our sins and wrongdoing, or are we are to regard Him in awe, reverence, and majesty? This question is vital, since how we answer it will affect how we are to walk (לָלֶכֶת) in God's ways, how we are to love (לְאַהֲבָה) Him, and how we are to serve (לַעֲבד) the LORD with all our heart and soul (Deut. 10:12).

Both Jewish and Christian traditions have tended to regard yirah to mean fear of God's retribution for our sins. "For we know him who said, 'Vengeance is mine; I will repay.' And again, 'The Lord will judge his people' (Heb. 10:30). God is the Judge of the Universe, and people will be recompensed according to their deeds, whether good or bad. Our lives should be governed by the rewards and punishments that await us in the world to come. We should tremble before the LORD because we are entirely accountable for our lives. We should fear sin within our hearts. Our actions matter, and we should dread the thought of angering God. There will be a final day of reckoning for us all...

The Chofetz Chaim warns that even though the fear of God's punishment may deter us from sin in the short run, by itself it is insufficient for spiritual life, since it is based on an incomplete idea about God. It sees God in terms of the attributes of justice (אלהִים) but overlooks God as the Compassionate Savior of life (יהוה). After all, if you are avoiding sin only because you fear God's punishment, you may clean the "outside of the cup" while the inside is still full of corruption... Or you might attempt to find rationalizations to excuse yourself from "legal liability." You may appear outwardly religious (i.e., "obedient," "Torah observant," "righteous"), but inwardly you may be in a state of alienation and rebellion. "The heart is deceitful above all things..."

Yeshua taught that we need a spiritual rebirth in order to see the Kingdom of God (John 3:3). This is the new principle of life from God (i.e., chayim chadashim: חַיִּים חֲדָשִׁים) that operates according to the "law of the Spirit of life" (Rom. 7:23, 8:2). God loves His children with "an everlasting love" (i.e., ahavat olam: אַהֲבַת עוֹלָם) and draws us to Himself in chesed (חֶסֶד, i.e., His faithful love and kindness). As it is written: אַהֲבַת עוֹלָם אֲהַבְתִּיךְ עַל־כֵּן מְשַׁכְתִּיךְ חָסֶד / "I love you with an everlasting love; therefore in chesed I draw you to me" (Jer. 31:3). Note that the word translated "I draw you" comes from the Hebrew word mashakh (מָשַׁךְ), meaning to "seize" or "drag away" (the ancient Greek translation used the verb helko (ἕλκω) to express the same idea). As Yeshua said, "No one is able to come to me unless he is "dragged away" (ἑλκύσῃ, same word) by the Father" (John 6:44). God's chesed seizes us, takes us captive, and leads us to the Savior... Spiritual rebirth is a divine act of creation, "not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God" (John 1:13). God is always preeminent.

Those who understand the mission of Yeshua understand yirah in the highest sense of reverence and awe. Only at the Cross may it be said: חֶסֶד־וֶאֱמֶת נִפְגָּשׁוּ צֶדֶק וְשָׁלוֹם נָשָׁקוּ - "love and truth have met, righteousness and peace have kissed" (Psalm 85:10). For at the Cross of Yeshua we see both God's fearful wrath for sin as well as God's awesome love for us. "Therefore, since we are receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken, let us be thankful, and so worship God acceptably with reverence and awe (μετὰ αἰδοῦς καὶ εὐλαβείας) - for our God is a consuming fire" (Heb. 12:28-29).

חֶסֶד־וֶאֱמֶת נִפְגָּשׁוּ צֶדֶק וְשָׁלוֹם נָשָׁקוּ

che·sed ve·e·met nif·ga·shu, tzedek ve·sha·lom na·sha·ku

"Love and truth have met, justice and peace have kissed." (Psalm 85:10)

Download Blessing Card

Rabbi Hanina wrote: "Everything is in the hand of heaven except the awe of heaven, as it says, 'And now, Israel, what does the Eternal your God require of you? Only to be in awe of the Eternal your God" (Berachot 33b). It is a struggle to see and think clearly. Many of us have become so dulled and jaded by our worldly concerns that we can barely open our eyes to behold the glories all around us. We walk around half asleep, yawning our way through the cosmic glory that surrounds us.

We must cultivate awe in our hearts by consciously remembering the LORD's Presence and salvation. As King David said:

שִׁוִּיתִי יהוה לְנֶגְדִּי תָמִיד כִּי מִימִינִי בַּל־אֶמּוֹט

shi·vi·ti Adonai le·neg·di ta·mid, ki mi·mi·ni bal e·mot

"I have set the LORD always before me; because he is at my right hand,

I shall not be shaken." (Psalm 16:8)

Some of the sages interpret this verse to mean that we should picture the Shekhinah Presence in front of us at all times. In Jewish tradition, a type of meditative artwork called "shivitis" have been designed to remind us that we are standing in the Presence of God. Often these are placed on the eastern wall of a synagogue. Shivitis are artistic renderings of the statement, "Know before whom you stand" (in Hebrew: דַּע לִפְנֵי מִי אַתָּה עוֹמֵד - da lifnei mi attah omed). Sometimes shivitis are also performed orally, as the repetition of a particular verse of Scripture. These techniques are meant to instill within us the sense that God's glory fills the whole earth and that we owe our lives to Him. Since each person is created b'tzelem Elohim (in the image of God), Martin Buber regards each person that stands before us as a "shiviti" - a reminder of God's presence.

Note the paradoxes involved in this verse. We set the LORD always before us (shiviti Adonai lenegdi tamid) so that we will not be shaken, and yet we are to revere the LORD with fear and trembling (Psalm 2:11, Phil. 2:12). Likewise, we draw near to the LORD God as the Righteous Judge - in fear and trepidation - yet in the full confidence of His love as demonstrated by the Cross of Yeshua. God is a Consuming Fire, but also our Comforter.

In the Talmud it is written, "As to the one who reveres God, the whole world was created for that person's sake. That person is equal in worth to the whole world" (Berachot 6b). This might be hyperbole, but it reminds me of the Chassidic tale that says says that every person should walk through life with two notes, one in each pocket. On one note should be the words bishvili nivra ha'olam (בִּשְׁבִילִי נִבְרָא הָעוֹלָם) -- "For my sake was this world created," and on the other note the words, anokhi afar ve'efer (אָנכִי עָפָר וָאֵפֶר) -- "I am but dust and ashes."

Similarly, it is evident that both senses of yirah are called for within our hearts. We must fear the LORD as our Judge and yet be in awe of the cost of His Redemption. We draw close to God while regarding Him with exalted reverence. We should constantly fear sin. We should be afraid of stumbling and dishonoring God with our lives. We should be vigilant, alert, awake, mindful, and attentive to the Presence of the LORD in all things. Sin "misses the mark" regarding our high calling and status as God's children.

|

"Know before whom you stand" - da lifnei mi attah omed. A reverent and focused attitude means "practicing the Presence of God" in our daily lives. The whole earth is filled with His glory, if we have the eye of faith to see (Isa. 6:3). We are surrounded by God's loving Presence and nothing can separate us from His love (Rom. 8:38-39). In Him we "live and move and have our being" (Acts 17:28). God will never leave us nor forsake us (Heb. 13:5). He has said, "Do not fear, for I am with you; do not be dismayed, for I am your God. I will strengthen you and help you; I will uphold you with my righteous right hand" (Isa. 41:10).

When we identify with the substitutionary death of Yeshua as our Sin-Bearer before the Father, we accept God's righteous verdict for our sin. My sin put Yeshua on the cross. My sin caused Him to bleed, to suffer, and to die... Yeshua took my place on the cross so that I would not have to endure the penalty warranted for my crimes. This is a fearful thing, connected with the punishment for sin, and therefore answers to the heart's fear of God as the Righteous Judge (yirat ha-malkhut: יִרְאַת הַמַּלְכוּת). The fearful consequences of sin comes first, since it is only by means of the sacrificial death of Yeshua that we may hope for forgiveness...

The good news is that the sacrifice of Yeshua reconciles us to God by exchanging God's judgment for your sin with the righteousness of Messiah. Indeed, the Greek word translated "reconciliation" is katallage (καταλλαγή), which means to exchange one thing for another (Rom. 5:10; 1 Cor. 7:11; 2 Cor. 5:18, 20, Col. 1:21, etc.). This "exchange" is imputed to you solely through faith in the merit of Yeshua as your Sin-Bearer before the Father. Yeshua "entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thereby securing an eternal redemption (αἰωνίαν λύτρωσιν for גְּאוּלַּת עוֹלָם). This was part of God's eternal plan to redeem the world from the curse of sin (Eph. 1:4; Heb. 9:12; John 17:24; Col. 1:22; Heb. 9;26, 10:10; 1 Pet. 1:20; Rev. 13:8). Therefore "there is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear, because fear is connected to punishment (κόλασις / הָענֶשׁ), and and whoever fears in this way has not been perfected in love" (1 John 4:18). The judgment against your sin was made at the Cross and you are now declared righteous by faith (2 Cor. 5:21, Col. 1:22). God regards you in light of the sacrifice of His Son, and the payment for your sins has been fully made (Rom. 5:6-10; 1 Pet. 2:24; 3:18; Col. 1:20-22; 1 Tim. 2:6; Gal. 3:13; Heb. 9:12). If you are trusting in God's salvation, your fear of punishment for your sins comes will come to an end...

But the good news gets even better. The "divine exchange" of our sin for Yeshua's righteousness also means that we exchange our natural life with the life represented by Yeshua's resurrection... Yeshua came to destroy the one who has the power of death (the devil) and "to deliver those who through fear of death are subject to lifelong slavery" (Heb. 2:14-15). The resurrection demonstrates that God is LORD over the law's judgment of sin (and therefore the "authority of death"). Yeshua's death as our Sin-bearer before the Law's verdict was answered by the power of the resurrection (Col. 2:13-14). "The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law" (1 Cor. 15:56). Once Yeshua made satisfaction for sin through obedience to the Law, He rendered death powerless. God's love overcomes the law's verdict (and God's wrath) by bearing it on our behalf. Yeshua's victory over the law is the victory of God's ransoming love. The resurrection ensures that the sacrifice made by God to God was one where love and justice kiss (Psalm 85:10). We are now free to serve God according to the "law of the Spirit of Life" (תוֹרַת רוּחַ הַחַיִּים) -- apart from the "law of sin and death" (תּוֹרַת הַחֵטְא וְהַמָּוֶת) -- by means of the resurrection power of God's life within our hearts (Rom. 8:2). We are now free to come boldly before the "Throne of Grace" to find mercy and grace to help in time of need (Heb. 4:16).

If anyone is "in the Messiah" he is briah chadashah (בְּרִיאָה חֲדָשָׁה), a "new creation." The old has passed away, behold - all things are made new (2 Cor. 5:17). The very power that raised Yeshua from the dead now dwells in you (Rom. 8:11). The miracle of new life is "Messiah in you - the hope of glory" (Col. 1:27). Ultimately the goal of salvation was not simply to save us from the power of sin and death, but to unite us with God in eternal love. You were redeemed to be a true child of God, no longer a slave to fear of death...

It is the combination of fear and love that leads us to the place of genuine awe. At the Cross we see God's passionate hatred for sin as well as God's awesome love for sinners. The resurrection of Yeshua represents God's vindicating love. We stand in awe of God because of His love and His righteousness. He is both "just" and the "justifier" of those who are trusting in His salvation (Rom. 3:21-26).

We usually make a distinction between "faith" and "fear," but this distinction needs to be somwhat qualified. Sometimes fear implies the absence of faith, and we are commanded to banish such from our hearts: "Al Tirah: Fear not, for I am with you" (Isa. 41:10). But when we approach God, we should be in fear (yirah), showing reverence and humilty. Our faith in God's love should never remove awe and reverence from our hearts. On the contrary, true faith is intimately connected with the vision of God's majesty and glory, and that glory is most clearly seen in the sacrificial death and resurrection of His Son....

May you fall before the cross in fear of your sins, but may you be raised up by the power of God's salvation... May you then walk in awe of God's ways, "to love him, to serve the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul." Amen.

Prayer Request...

07.26.10 (Av 15, 5770) Please keep this ministry in your prayers... I am dealing with chronic pain issues as well as some other challenges. Thank you. - John

Parashat Eikev - עקב

[ The following concerns this week's Torah reading, parashat Eikev. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here... ]

07.26.10 (Av 15, 5770) The Torah portion for this coming Shabbat (Eikev) includes the famous statement: "Man does not live by bread alone, but from everything that comes from the mouth of the LORD shall he live" (Deut. 8:3). Note that Yeshua quoted this verse when he was tested with physical hunger in the wilderness (Matt. 4:3-4).

כִּי לא עַל־הַלֶּחֶם לְבַדּוֹ יִחְיֶה הָאָדָם

כִּי עַל־כָּל־מוֹצָא פִי־יהוה יִחְיֶה הָאָדָם׃

ki lo al-ha·le·chem le·va·do yich·yeh ha·a·dam;

ki al-kol-mo·tza fi-Adonai yich·yeh ha·a·dam

"Man does not live on bread alone, but by everything that comes

from the mouth of the LORD does man live" (Deut. 8:3)

Although physical food helps us survive, we must ask the question, for what end? Do we live for the sake of eating (and thereby live to eat for another day, and so on), or do we eat in order to live? If the latter, then what is the goal of such life? What is the source of its nutrient and where is it taking you? What does your soul or "inner man" feed upon to gain the spiritual will to live?

Both the written Torah and Yeshua (who is the embodiment and expression of Torah) make it clear that we receive sustenance from the Word of God (דְּבַר הָאֱלהִים), the Source of spiritual life. But the word of God itself is a message of the very love of God (אַהֲבַת הָאֱלהִים) that is always sustaining us -- whether we are conscious of this or not. After all, for those of us who understand our brokenness and radical dependence, what "word" could we possibly endure were it not His words of hope, consolation, and even endearment? The Love of God is our life, chaverim, and the love of God is most clearly seen in the life and sacrificial death of Yeshua the Messiah...

God cleaves to us and therefore calls us to cleave to Him in return (devakut). Some scholars think that the Hebrew word for seeing (ראה) and the word for fearing (ירא) share the same root, and therefore we can close our spiritual eyes by not revering the works of the LORD. Similarly, we can close our spiritual ears by not heeding to His words of love for our soul...

Our very spiritual life -- its source and its end -- depends upon receiving the word of the Living God who is King of Eternity (אֱלהִים חַיִּים וּמֶלֶךְ עוֹלָם). He speaks words of hope and love to those who attend themselves to His Presence. May you hear Him speaking to you now!

Shabbat Va'tomer (שׁבּת וַתּאמֶר)

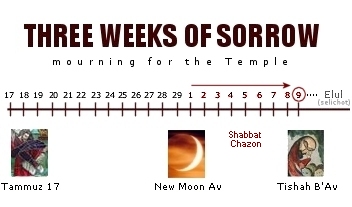

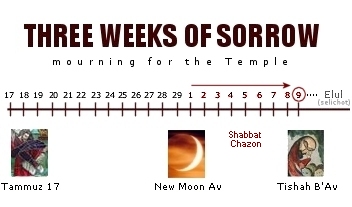

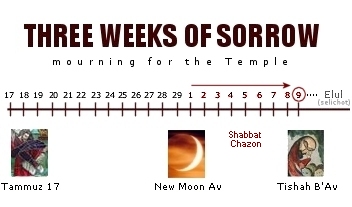

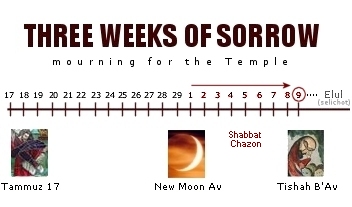

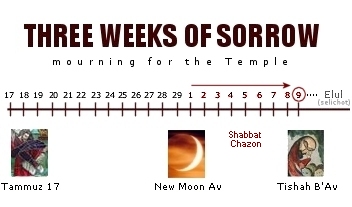

The weekly haftarah portion (reading from the Prophets) is usually connected with the weekly Torah portion. However, beginning from the 17th of Tammuz until the end of the Jewish year, the connection changes. First three haftarot of rebuke are read during the "Three Weeks of Sorrow" (between the 17th of Tammuz and Tish'ah B'Av), and then seven haftarot of comfort (Shiva D'Nechemta) follow until the end of the year (i.e., until Rosh Hashanah). These seven selections from the prophets foretell the restoration of the Jewish people to their land (the ingathering of the exiles), the future redemption of Israel, and the coming of the Messianic Era.

This week (the second of the Seven Weeks of Comfort) is called Vatomer Tzion (וַתּאמֶר צִיּוֹן, "And Tzion shall say"), which commands us to never regard Zion as abandoned.... "Can a woman forget her nursing child, that she should have no compassion on the son of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you. Behold, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands; your walls are continually before me" (Isa. 49:15-16). The Haftarah concludes by Isaiah saying that the LORD will comfort the Mountain of Zion by making it like the Garden of Eden, with joy and happiness within her, along with thanksgiving and the sound of song.

Note: The month of Elul begins in just a couple of weeks (i.e., on August 10th this year), and Rosh Hashanah itself occurs in just six weeks (Sept. 8th at sundown). These seven Haftarot of comfort are intended to encourage us to get ready for the High Holiday Season.

A Jewish "Valentine's Day"?

07.26.10 (Av 15, 5770) Hebrew letters can be used to express numbers. Joining the letters Tet (9) and Vav (6), for example, equals the number 15, sometimes written as the acronym "Tu" (ט"ו). The phrase "Tu B'Av" (ט"ו באב) indicates the 15th day of the month of Av (אָב), a "full-moon" holiday that has been celebrated as a day of love and affection since Biblical times (i.e., chag ha-ahavah: חַג הָאַהֲבָה). In modern Israel it is customary to send a bouquet of red roses to the one you love on Tu B'Av. Romantic songs are played on the radio and parties are held in the evening throughout the country. This year Tu B'Av occurs July 26th, 2010.

The first mention of Tu B'Av is found in the Mishnah, where Shimon ben Gamliel is quoted as saying, "There were no better (i.e. happier) days for the people of Israel than the Fifteenth of Av and Yom Kippur, since on these days the daughters of Israel go out dressed in white and dance in the vineyards. What were they saying: Young man, consider whom you choose to be your wife... (Taanit, Chapter 4).

Since it is the "last" festival of the Jewish year, prophetically Tu B'Av pictures our marriage to the Lamb of God (Seh Elohim), the LORD Yeshua our beloved Messiah. On a soon-coming day those who belong to the LORD and are faithful to follow His ways will be blessed with the unspeakable joy of consummating their relationship with Him. This is heaven itself - to be in the Presence of the LORD and to be His beloved (Rev. 19:6-9).

For more about Tu B'Av, click here.

Parashat Vaetchanan - ואתחנן

[ The following concerns this week's Torah reading, parashat Vaetchanan, which is always read on the Sabbath following Tishah B'av. Please read the Torah portion to "find your place" here. ]

07.23.10 (Av 12, 5770) During Tishah B'Av we restrict our study of Torah to the grave matter of God's judgment for our sins. We read the prophet Jeremiah and grieve over the destruction of the Temple. We weep over the lost vision of Zion - and the exile of the Jewish people. This is a somber time of national mourning for Israel...

But there is always hope, even in our darkest hour.... The Sabbath immediately following Tishah B'Av is called Shabbat Nachamu (שבת נחמו ), "the Sabbath of Comfort," because we take time to remember Israel's prophetic future. The Haftarah therefore begins: Nachamu, nachamu ammi (נַחֲמוּ נַחֲמוּ עַמִּי) "Comfort, comfort, my people, says your God" (Isa. 40:1). And because the study of Torah brings comfort and joy to our hearts, the sages chose parashat Vaetchanan to be read at this time to emphasize our duty to study the Torah (תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה) and to rejoice in the revelation of God:

פִּקּוּדֵי יהוה יְשָׁרִים מְשַׂמְּחֵי־לֵב

מִצְוַת יהוה בָּרָה מְאִירַת עֵינָיִם׃

pik·ku·dei Adonai ye·sha·rim, me·sa·me·chei lev;

mitz·vat Adonai ba·rah, me·i·rat ein·na·yim

"The enumerations (פִּקּוּד) of ADONAI are right, rejoicing the heart;

The mitzvah of ADONAI is pure, bringing light (אוֹר) to the eyes." (Psalm 19:10)

The Torah portion begins with Moses' plea to the LORD to be allowed entry into the Promised Land, despite God's earlier decree (Num. 20:8-12; 27:12-14). The Hebrew word va'etchanan (וָאֶתְחַנַּן) comes from the verb chanan (חָנַן), which means to beseech or implore. It derives from the noun chen (חֵן), grace, implying that the supplication appeal's to God's favor, not to any idea of personal merit (in Jewish tradition, tachanun (תַּחֲנוּן) are prayers recited after the Amidah begging for God's grace and mercy). Moses was asking God to show him grace by reversing the decree that forbade him to enter the Promised Land.

Note that in Jewish tradition, the idea of appealing to God's grace is not without expending personal effort. The gematria of vaetchanan is 515 -- the same as the word for prayer (i.e., tefillah, תְּפִלָּה) -- which suggests (according to some of the sages) that Moses offered tachanunim (supplications) no less than 515 times to be allowed into the Promised Land. Despite his repeated appeals, however, God finally said to Moses: רַב־לָך, "enough from you" (Deut. 3:26) and reaffirmed His decree that he would not be allowed to lead Israel into the land. That privilege was given to Yehoshua bin Nun (יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן־נוּן), i.e., "Joshua the son of Nun," who was clearly a picture of the Messiah.

Moses was forbidden into the land because symbolically the covenant made at Sinai was insufficient to fulfill the promise of God. This insufficiency, however, was not the fault of God's Torah, which is "holy, just, and good" (Rom. 7:12), but rather because of the weakness of the human condition (i.e., the law of sin and death). "For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do. By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit" (Rom. 8:3-4). The New Covenant was needed to bring people to Zion, and this required a "change in the Torah" and a new priesthood (Heb. 7:12). "The former commandment was set aside because of its weakness and uselessness - for the law made nothing perfect - but a better hope is introduced, and that is how we draw near to God" (Heb. 7:18-19).

The sages refer to the principle: ma'aseh avot siman labanim (מַעֲשֵׂה אֲבוֹת סִימָן לַבָּנִים): "The deeds of the fathers are signs for the children." The entire Exodus story amounted to a sort of parable: "As below, so above" (and conversely). In Jewish midrash, the rock is called the "well of Miriam" because the water was said to have run dry upon her death. But this is simply a midrash, and we know from the New Testament that both the manna (i.e., lechem ha-chayim: לֶחֶם הַחַיִּים) and the living water (i.e., mayim ha-chayim: מַיִם הַחַיִּים) both represented the Presence of Yeshua (John 6:35; 7:38). "Our fathers ... passed through the sea and ate the same spiritual food and drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was the Messiah" (1 Cor. 10:1-4). This Rock was not given to Israel in the merit of Miriam, but rather foreshadowed the sustenance of life given through the One who would be stricken for His people (Isa. 53:4 and 1 Cor. 10:4). The Torah states that Moses' sin that led to his exile was that he "struck the rock twice" (Chukat), and this implied that the Savior of Israel would need to be stricken a second time to give life the people. No! The Rock that was once smitten for the people was now to be spoken to as the "Living Rock" (Num. 20:8, 1 Cor. 10:4).

Even in the face of exile, we know that God's correction and judgment is not the last word for those who turn to Him in trust (Lam. 3:22-23). In the end, the Jewish people will be saved (Rom. 11:26), just as Moses was indeed later admitted to the Promised Land where he met with Yeshua on the Mount of Transfiguration (Matt. 17:1-5). The LORD is faithful and true, and He will never break His promise to the children of Israel...

חַסְדֵי יְהוָה כִּי לא־תָמְנוּ כִּי לא־כָלוּ רַחֲמָיו׃

חֲדָשִׁים לַבְּקָרִים רַבָּה אֱמוּנָתֶךָ׃

chas·dei Adonai ki lo-ta·me·nu, ki lo-kha·lu ra·cha·mav,

cha·da·shim la·be·ka·rim rab·bah e·mu·na·te·kha

"The faithful love of the LORD never ceases; his mercies never come to an end;

they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness" (Lam. 3:22-23)

Shabbat Shalom, chaverim!

Jeremiah and Jesus...

[ It is hard to overstate the significance of the destruction of the Jewish Temple by the Babylonians in 586 BC. Its demolition - and the exile of Judah - is perhaps the central calamity of the entire Tanakh (even today Judaism grapples with its implications). The prophet of that dark period of Jewish history was Jeremiah, sometimes called the "weeping prophet." In many profound ways Jeremiah prefigured the prophetic ministry of Yeshua. The following entry continues the theme found in the Haftarah of Tishah B'Av.... ]

07.22.10 (Av 11, 5770) Francis Schaeffer once identified Jeremiah as the quintessential prophet for the postmodern age. "Jeremiah," he wrote, "provides us with an extended study of an era like our own, where men have turned away from God, and society has become post-Christian" (Schaeffer: Death in the City). The rabbis called him the "Weeping Prophet," and not without reason. His entire mission was to herald sorrow, destruction, and hardship for the people of God... As he finally saw the Holy Temple burn to the ground, it surely must have seemed as if his entire ministry had failed...

The prophet Jeremiah (i.e., Yirmeyahu ha-navi: יִרְמְיָהוּ הַנָּבִיא) is generally regarded as one of the three "major" Jewish prophets (the other two being Isaiah and Ezekiel). He lived from about 640-570 BC and began serving as God's prophet during the 13th year of King Josiah's reign. Jeremiah's long ministry would subsequently span the reigns of five different kings of Judah: Josiah (640–609 BC), Jehoahaz (609 BC), Jehoiakim (609-598 BC), Jehoiachin (598-597 BC), and Zedekiah, the last king of Judah (597-586 BC).

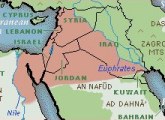

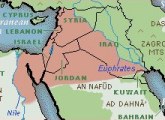

Over the course of his 40 year ministry, Jeremiah saw the abrupt fall of the Assyrian Empire and the steady rise of Babylonian dominance in the Ancient Near East. He witnessed prince Nebuchadnezzar's rise to power and understood the significance of his military campaign against Egypt at the battle of Carchemish in 605 BC. He foresaw that the political future of Judah would turn on the conflict between Babylon and Egypt:

|

Jeremiah was living in Jerusalem when Nebuchadnezzar (who by then had become king of Babylon) returned to capture the city in 597 BC. At that time Nebuchadnezzar deposed the Jewish king Jehoiachin and installed Zedekiah (צִדְקִיָּה) as his vassal (2 Kings 24:12,17). During Zedekiah's rule, Jeremiah advised the leadership of Judah to submit to Babylonian rule and not to look to Egypt as a political ally (Jer. 2:18,36; 37:7-8; etc.). Judah needed to accept the fact that its destruction was imminent and inevitable (Jer. 5:15-17). Because of his doom-laden prophecies, Jeremiah was regarded as a fatalist and a defeatist. The leaders of Judah rejected his message and regarded him as a traitor. His religious critics (i.e., the Levites and Temple administration) regarded him as a false prophet who did not believe in the doctrine of Zion's invincibility (Jer. 7:4). In particular, Jeremiah took issue with those who believed that the Temple functioned as some sort of "good luck charm" to ward off the threat of destruction from Judah.

"Do not trust in these deceptive words: 'This is the temple of the LORD, the temple of the LORD, the Temple of the LORD.' For if you truly amend your ways and your deeds, if you truly execute justice one with another, if you do not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow, or shed innocent blood in this place, and if you do not go after other gods to your own harm, then I will let you dwell in this place, in the land that I gave of old to your fathers forever. But you trust in deceptive words to no avail" (Jer. 7:5-8).

Do not trust in these deceptive words: "This is the temple of the LORD,

the temple of the LORD, the temple of the LORD." - Jer. 7:4

Jeremiah went on to condemn the "lip service" exemplified by the corrupted Temple and its public worship services: "Will you steal, murder, commit adultery, swear falsely, make offerings to Baal, and go after other gods that you have not known, and then come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my Name, and say, 'We are delivered!' - only to go on doing all these abominations? I will do to the house that is called by my Name, and in which you trust, and to the place that I gave to you and to your fathers, as I did to Shiloh. And I will cast you out of my sight, as I cast out your kinsmen, the offspring of Ephraim" (Jer. 7:9-15).

Jeremiah's condemnation is clearly similar to that of Yeshua, who overthrew the money changer's tables, stopped the daily sacrifice, and charged the priestly leadership with making His Father's house a "den of robbers" (Jer. 7:11, Matt. 21:13, Mark 11:15-17; Luke 19:45-46). Like Jeremiah, Yeshua insisted that the "kingdom of God is within you," that is, a matter of the heart of faith. There is no inherent sanctity of a physical place apart from a heart that is trusting in the LORD's love and righteousness (Jer. 7:4-7; Luke 17:21). Indeed, Yeshua's harshest words were directed to religious leaders who made a pretense of their devotion to God, but were inwardly full of greed and self-deception:

"Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you clean the outside of the cup and the plate, but inside they are full of greed and self-indulgence. You blind Pharisee! First clean the inside of the cup and the plate, that the outside also may be clean. Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you are like whitewashed tombs, which outwardly appear beautiful, but within are full of dead people's bones and all uncleanness. So you also outwardly appear righteous to others, but within you are full of hypocrisy and lawlessness" (Matt. 23:25-28).

The "outer is not the inner," and vice versa. God abhors those who pretend to know Him but who are spiritual impostors (Matt. 7:21-23; 25:11-12; Luke 6:46). Because of such rampant hypocrisy, both Jeremiah and Yeshua denounced the Temple as utterly corrupt and foretold its destruction (Jer. 25:9,11; Matt. 24:1-2).

Yeshua warned us about the "leaven" (i.e., doctrine - διδαχή) of the Pharisees, Sadducees, and politicians of his day (Matt. 16:6-12; Mark 8:15). In Luke's Gospel, this leaven is defined as hypocrisy (ὑπόκρισις): "Beware of the leaven of the Pharisees, which is hypocrisy (Luke 12:1)." But what is hypocrisy? The word might come from the Greek prefix ὑπὸ (under) combined with the verb κρίνω (to judge), and hence refers to the inability to come to a decision and exercise genuine conviction. It is a state of being "double minded," duplicitous, and insincere... Later the word connoted playing a part, "putting on a show," feigning righteousness, acting with insincerity, reusing "canned answers" or repeating the party line. Hypocrisy is therefore a form of self-deception. It is institutionalized prejudice dressed up as religion; it is counterfeit thinking that cheats the truth; it is ethnocentric nonsense that despises others as unworthy, inferior, etc. The "leaven of the Pharisees" is like old sourdough added to the community -- it "puffs people up" and is therefore based on human pride. The message of both Jeremiah and Yeshua was marked by repentance, humility, and the sincere desire to love and serve God.

The prophet Jeremiah clearly foreshadowed the prophetic ministry of Yeshua our Messiah. Both Jeremiah and Yeshua were called to deliver the judgment of God upon sinful man. Both lived in a time of political upheaval and unrest for Judah. In a sense, both were "prophets of doom" who became "enemies of the Jewish state." Both condemned hypocrisy and foretold disaster unless the people turned away from sin and turned to God with all their hearts (Matt. 15:8; Jer. 7:9-15). Both were "weeping prophets" who lamented over the City of Jerusalem (Jer. 9:1; Luke 19:41). Both were misunderstood and persecuted by the people of their day. Both prophets were plotted against by the citizens of their own hometowns (Jer. 11:21; Luke 4:28-30), and both were rejected by the religious and political leaders of their day (Jer. 20:1-2; John 18:13, 24). Both rejected the Temple worship as corrupt and beyond repair. Both condemned the "religious" reinterpretation of the Torah (Jer. 8:8; Matt. 23:2-3;23; Mark 7:5). Both were forcibly taken into Egypt because of political persecution (Matt. 2:13; Jer. 44). Both were falsely accused, arrested, and unjustly beaten (Jer. 37:12-15; Matt. 26:61; 27:26). Both were rejected by the secular Jewish king of the Jews (Jer. 32:2-4; Luke 23:8-11). And yet both never abandoned the Jewish people and ultimately offered God's comfort and hope (Lam. 3:22-25, John 14:1,27). Jeremiah and Yeshua both preached the New Covenant (בְּרִית חֲדָשָׁה) of God that would transform a heart of stone into a heart of flesh (Jer. 31:31-34; Luke 22:20; Heb. 8:6-13; 9:15, etc.). Both foresaw that the true Temple of God was made without hands, built from material of hearts of those who truly serve God in Spirit and in truth... The destruction of the First Temple was the central catastrophe of the older covenant, just as the destruction of the Second Temple was the central catastrophe of the New Covenant. Because of the suffering and sacrificial death of Yeshua, the inner veil of the Temple has forever been rent asunder, and access to the Presence of God has been made available to all who trust in Him....

Because of his radical prophecies of doom, king Zedekiah eventually arrested Jeremiah and put him in the palace prison. Later Jeremiah witnessed the destruction of the city in fulfillment of his prophecies (Jer. 32:2-5; 38:28).

Like other prophets of the LORD, Jeremiah decried the false teachers and injustices of his day. "No one relents of his evil saying, 'What have I done?' Everyone turns to his own course, like a horse rushing for battle" (Jer. 8:6). And though he was of priestly lineage himself, he regarded the Temple in Jerusalem to be as corrupt as the Northern Kingdom's shrine at Shiloh (Jer. 7:4-15). He rejected the priest's narrow interpretation of the law as entirely deceitful (Jer. 8:8). Indeed, the entire culture was based on greed and deception, "from prophet to priest," everyone dealt falsely. "They have healed the wound of my people lightly, saying, 'Peace, peace,' when there is no peace" (שָׁלוֹם שָׁלוֹם וְאֵין שָׁלוֹם). This lead to Jeremiah's apocalyptic warning of the coming destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of the Jewish people (Jer. 25:9,11).

Around 590 BC, Zedekiah and the Jewish leadership of Judah openly rebelled against Babylon (2 Kings 24:18-20). This act of defiance prompted Nebuchadnezzar to besiege Jerusalem in 588 BC (on the 10th of Tevet; 2 Kings 25:1). After the two-year siege, Jerusalem ran out of food, and the walls were breached (on the 17th of Tammuz). Zedekiah's family was killed, and the king was blinded, bound, and sent to Babylon (2 Kings 25:7). The Temple, the palace, and all of the houses of Jerusalem were destroyed (on the 9th of Av), and the remaining treasures from the Temple were taken to Babylon (2 Kings 25:8-17). The majority of the Jews were displaced to Babylon and "only the poorest people of the land" remained. Nebuchadnezzar installed a man named Gedaliah to function as his governor (2 Kings 25:22). Zedekiah proved to be Judah's last king...

Jeremiah did not go with the Jews into exile, however, but was released from Zedekiah's prison to function as a liaison under a Gedaliah (Jer. 39:13-14; 40:6). He urged the Jews who remained in the land to submit to Babylonian rule and not to rebel (Jer. 27:11; 38:17). Despite his warnings, however, Gedaliah was murdered by Ishmael the son of Netaniah (who apparently regarded himself as a Davidic heir to the throne) and his gang of ten zealots (2 Kings 25:25). After Gedaliah's murder, the local Jews feared reprisal from Nebuchadnezzar and considered fleeing to Egypt to save themselves. Jeremiah warned them not to flee since the sword from which they were running would slay them there (Jer. 42:16-22). Unfortunately, the people disregarded Jeremiah's words and fled to Egypt anyway. Worse still, they abducted the prophet and took him with them (Jer. 43:2-7). A few years later Babylon conquered Egypt and tens of thousands of these Jewish refugees were killed (on the 3rd of Tishri). Jewish tradition says that Jeremiah was later stoned to death in Egypt for denouncing the idolatry of the surviving Jews who had fled there (Jer. 44).

Jeremiah's prophecies (as compiled by his faithful scribe, Baruch) were later collected into the "Book of Jeremiah" which is part of the Jewish canon of Scripture. The material in the book is thought to cover 30 years, though not in chronological order. Jeremiah is also credited as the author of the acrostic poem found in the scroll of Eichah (i.e., the "Book of Lamentations"). In Jewish tradition, Jeremiah is not regarded to be as great as Isaiah: "All the harsh prophecies which Jeremiah would prophecy against Israel, Isaiah preceded and provided the healing" (Eichah Rabati 1:23).

Midrashim about Jeremiah

Jeremiah was born in the small town of Anatot, about 3 miles northeast of Jerusalem. He is identified as a descendant of Rahab the harlot (רָחָב הַזּוֹנָה) by her marriage with Joshua, the successor of Moses (Sifre, Num. 78). His father Hilkiah was a Temple priest. According to midrash, he was prophetically born on Tishah B'Av to foreshadow his ministry of doom (Jer. 20:14). According to legend, it was evident that Jeremiah was destined for greatness from birth, since he born circumcised (Avot d'Rabbi Nosson). "Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you; I appointed you a prophet to the nations" (Jer. 1:5). Jeremiah is said to have emerged from his mother's womb with a "great cry," which was said to foreshadow his lament for the destruction of Jerusalem. As a very young boy Jeremiah is said to have looked intently at his mother and said: "Mother, Mother, you did not conceive me in the way of women, and your path was that of the wayward woman. You set your eyes on another man and strayed from your husband. Why do you not drink the bitter waters of the sotah? You have been brazen-faced." When his mother asked, "Why do you speak to me this way?" Jeremiah replied, "I am not speaking about you, Mother; I am prophesying about Zion and Jerusalem" (Pesikta Rabbasi). Later God commanded Jeremiah not to marry and have a family because the coming judgment on Judah would sweep away the next generation (Jer. 16:1-4). Jeremiah often expressed his anguish of spirit which lent itself to his designation as the "weeping prophet" (Jer. 4:19; 9:1; 10:19-20; 23:9, etc.)

The sages sometimes compare Moses and Jeremiah. "Everything that is written about Moses is written about Jeremiah. As Moses was a prophet for forty years, so was Jeremiah; as Moses prophesied concerning Judah and Benjamin, so did Jeremiah; as Moses' own tribe (the Levites under Korach) rose up against him, so did Jeremiah's tribe revolt against him (Jeremiah was a kohen); Moses was cast into the water, Jeremiah into a watery pit; as Moses was saved by a female slave (the slave of Pharaoh's daughter), so Jeremiah was rescued by a male slave (Jer. 38:7-13); Moses reprimanded the people in discourses, so did Jeremiah (Pesikta d'Rav Kahana). We may add that Jeremiah expressed the same reluctance as Moses to become a prophet and offered the same kind of excuses (God gave Aaron to be Moses' mouthpiece but directly put words into Jeremiah's mouth (Exod. 4:14-16, Jer. 1:8-9). Some scholars have said that Jeremiah might have even regarded himself as the coming prophet whom Moses foretold (Deut. 18:18).

As a young man, the LORD appeared to him and said, "Listen closely, Jeremiah. While you were still in your mother's womb, I sanctified you to be a prophet for My people. The time has now come for you to go forth and prophecy." Deeply moved and afraid of this responsibility, he replied: "Master of the universe, how can You send me to rebuke the Jews? They will kill me! They even threatened to kill Moses and Aaron, who led them from Egypt, and they mocked Elijah and Elisha. Who am I to deliver your message to them? I am young - only a child. Who will listen to me?" (Jer. 1:6). The LORD reassured Jeremiah: "Be not afraid. You shall indeed go wherever I send you. I have chosen you precisely because you are so young and innocent. Go to them and pour out my wrath upon them (Jer. 1:7-10).

Jeremiah was dismayed that he must be the "prophet of doom." "He said, 'Master of the Universe, what sins have I done that in the days of all the prophets who preceded me and those who will follow me, you did not destroy Your House, but only through me?' The LORD answered, 'Even before I created the world, you were prepared for this mission'" (Pesikta Rabati 27:5). Nonetheless, Jeremiah begged the LORD not to send him: "The day on which I was born was an evil one (Jer. 20:14); May this day never be blessed (Tishah B'Av)" He continued to protest. "Consider the differences between Moses and me. In his time, the Jews were told, 'May the LORD bless you (Num. 6:24),' but I must bring them a curse (Jer. 29:22). In Moses' day, You promised to protect your people and give them peace (Num. 6:26), but I must bring them news of evil days which will come to pass, days of darkness and death, of war and great tragedy (Jer. 16:5). Woe is me to be destined for such a bitter task! I am like a priest who discovers in the course of punishing the unfaithful woman that she is none other than my own mother! So I am consigned to deliver the news of exile and destruction to my people, who are as dear to me as my own mother!"

Jeremiah tried to make the people repent from their detestable Molech worship, the "king of fire" (the word "molech" is thought to be a corruption of the Hebrew word for king, melech: מֶלֶךְ, with the vowels of word "shame," boshet: בּוֹשֶׁת, added). This gigantic statue apparently had an ox's head, a hollow belly, and outstretched arms. It was said to have stood within a Canaanite temple that had seven chambers.

According to the Yalkut Shimoni (an collection of midrashim), a person who brought the "god" a gift of flour was allowed into the first chamber; a person who brought a gift of doves could enter the second chamber. A sheep gave access to the third, a ram to the fourth, a calf to the fifth, and a bull to the sixth. But if a true worshipper brought his infant son for sacrifice, he would be granted access to the seventh "grand" chamber of the Ammonite temple. The priests of Molech would heat up the belly of the idol and then burn the child to death in the idol's outstretched arms. Their frenetic drumming and shouts to the idol drowned out the screams of the baby. God sent prophets to warn the people to turn away from this horrible sin, which "had never entered His mind" (Jer. 32:35; Lev. 18:21; Deut. 18:10; 2 Kings 16:3; 17:17; 21:6; 23:10; 2 Chron. 33:6), but the people refused to repent. Nonetheless, God heard the cries of the babies and decreed that in punishment for these atrocities the Holy Temple itself would be sent up in flames....

When he saw the Jews so crazed with the fires of their idolatry, Jeremiah asked them, "Why do you pursue idols? What attracts you to such emptiness? The Jews replied, "We have forsaken the LORD and He is angry with us. That is why we seek comfort in our idols..." (Jer. 8:14). This midrash reveals the profound connection between our faith in God's love for us and our tendency toward sin. Despair over oneself can lead to shame, and shame leads to shameful actions (Prov. 13:5; 23:7). A person who abandons hope in the LORD and His love becomes a prey to the devil himself. If he no longer believes God can give him comfort, he will turn to the grossest forms of immorality to assuage his sense of abandonment.

According to Devarim Rabbah, "The Holy One, blessed be He, sent Jeremiah to the people when they sinned and said to them, 'Go tell my sons to repent.' The people said to Jeremiah, 'Should we return to the Holy One, blessed be He, with these faces? [i.e., we are ashamed to show our faces to Him].' The Holy One, blessed be He, sent Jeremiah again to tell them, 'My sons, if you return, is it not to your Father in heaven that you are returning? For He has never rejected you... By your lives, I will not deny my relationship with you. ' Nonetheless, despite such appeals, the people mocked Jeremiah and clung to their shame. It was the shame of sin that led to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, just as it was the shame of sin that led to the death of the exiles in Egypt....

Note: This is presently unfinished... If God wills, I will add more later. Shalom for now...

|

More Spiritual Warfare...

07.21.10 (Av 10, 5770) I just spent the last nine hours dealing with an apparent hacker attack on an uplink from my web hosting service... Oy! I was forced to restore hundreds of pages of content over here because of "unexplained" data loss on the server side. To make matters worse, I often could not restore the content because the attack was causing the server to be flooded... Finally, after hundreds of retries, I managed to get everything back (thank you, Lord). Please keep this ministry in your prayers, chaverim. The warfare is often intense (and exhausting) as I do this work. Thank you so much!

Note: I hope to add some additional commentary on this week's Torah portion (Vaetechan), as well as some fascinating information about Jeremiah the prophet later this week, if it pleases God. Shalom for now...

God's Lament for His People...

07.20.10 (Av 9, 5770) The tears of the prophet Jeremiah represent God's compassionate love for the Jewish people; the Book of Lamentations is really God's cry... God cares about the suffering of His people: b'khol tzaratam lo tzar (בְּכָל־צָרָתָם לוֹ צָר) - "In all their affliction he was afflicted" (Isa. 63:9). Even after all the horrors that befell the people of Judah due to God's disciplinary judgment, the LORD still encouraged them to seek Him again. "The faithful love of the LORD (חַסְדֵי יהוה) never ceases, and his compassions never fail. They are new every morning; great is your faithfulness" (Lam. 3:22-23). Our response to the faithful love of the LORD is teshuvah (i.e., תְּשׁוּבָה, "turning [shuv] to God"). In Modern Hebrew teshuvah means an "answer" to a shelah (שְׁאֵלָה), or a question. God's love for us is the question, and our teshuvah – our turning of the heart toward Him – is the answer. We return to the LORD when we truly acknowledge that He is our Father and our King:

הֲשִׁיבֵנוּ יהוה אֵלֶיךָ וְנָשׁוּבָה חַדֵּשׁ יָמֵינוּ כְּקֶדֶם

ha·shi·ve·nu Adonai e·ley·kha ve·na·shu·vah, cha·desh ya·me·nu ke·ke·dem

"Take us back, O LORD, to Yourself, And let us come back;

Renew our days as of old!" (Lam. 5:21)